In my last post I wrote about how rejection has become part of what makes me feel like a “real” writer. I also told a story about a college workshop where a guest speaker advised us to always introduce ourselves by saying, “Hi, I’m so-and-so, and I’m a writer.” But why? I think he wanted us to say it, over and over, not so that other people would know what we did, but so that we would believe it ourselves.

Imposter syndrome is a psychological occurrence marked by a persistent doubt of our own skills and abilities, accompanied by a sometimes intense feeling that we will be exposed as a fraud. However much we’ve been successful in the past at what we do, we convince ourselves that it isn’t really true—that we just fooled everyone, or got lucky, or that people are misperceiving us.

The term was originally developed in a 1978 paper examining the phenomenon in high-achieving women. “Despite external validation” by colleagues and other (supposedly) unbiased metrics like standardized testing, these women experienced “generalized anxiety, lack of self-confidence, depression, and frustration related to inability to meet self-imposed standards of achievement.” Later studies have confirmed that it exists at a roughly equal level in men as well. An estimated 70% of people have experienced “imposter syndrome” at some point in their lives.

Somewhat ironically, it probably must be repeated here: imposter syndrome is a real thing. It’s also incredibly common. (You’re not just making it up. You’re not the only one who feels it.)

It also isn't unique to writers or even those in the arts generally. But I do think that there might be specific variations on the syndrome that we deal with.

Let’s start by looking at the arts collectively. How does imposter syndrome differ there?

Well, I don’t see people in other occupations needing to go around stating their occupation like some kind of positive affirmation, for one thing.

My neighbor works at Bank of America and has a high-pressure job handling millions of dollars in investments every day. He may have his doubts on any given day that he really is a good investment banker. He has targets he may fail to hit, bosses and colleagues and clients who may expect him to perform financial miracles beyond his abilities. He may well feel sometimes that they all think he’s capable of doing much more than he really can, and in that way experiences imposter syndrome.

But he does not have to remind himself constantly that he really is an investment banker. He gets up, goes to his office, performs his duties, is regarded by others as exactly what he is— an investment banker. There's no doubt in his own mind that that's what he “is” even if he may doubt that he's good at it.

Let's say that another friend is self-employed. She runs an Etsy store, plans events, and also manages three AirBnB rentals. Now it's a bit harder to put a name to what she “is”—maybe she says she’s “self-employed” or “an entrepreneur,” or maybe she morphs, psychologically, from “small business owner” to “party planner” to “landlord” multiple times every day. It sounds completely exhausting and imposter-rich in yet another way. She also may doubt that she's good enough at what she does. But for all that, she does know she's doing something. No one would consider these things to be her hobbies. She's being paid for her time and efforts, or at least she has some plan for how she will grow her work and profit.

But with writing this isn't usually the case either. I do tons and tons and tons of work that certainly could lead to payment, someday, but often doesn't. My plan for growing my work and profiting is basically “write a novel that sells for a lot of money and brings in more work” and of course while I have a lot of control over the first part, I have very little over the second or third parts.

On top of this, I don’t have colleagues or clients like my hypothetical neighbors. I'm only rarely on the phone in a meeting, or having lunch to discuss ideas, or really even interacting with anybody else at all. Once every other month or so I will have coffee with another writer I know and we mostly try to encourage one another—or maybe just not depress each other too much—about how our work is going. I don’t get to call my boss after and say, “Yes sir, the big novella deal with David is coming along. We should have a proposal in by Friday.”

It just doesn’t work that way. I don’t have a boss to call. I don’t have a big novella deal or even a proposal due Friday. Instead I’ve got 198,000 words spread across seven documents all called something like “MYAWESOMENOVEL-final-final-FINAL8.docx”.

It looks like a whole lot of nothing to others. Some days it looks like that to me, too.

I combat this doubt by staying very busy. I might spend an afternoon sending a pitch for an essay, then revising a story, then scanning the internet for any news on my upcoming book release to share on social media, then applying for a grant, then actually writing, then getting stuck, then taking a walk in the woods where I can talk to myself without seeming too crazy so I can figure out the next scene, then back to revisions, then more new writing.

I might never, in all this time, sit at a desk or truly speak to anyone else about anything writing related.

And with all of this going on, unsure what profit or product might come, it still may seem indistinguishable from a hobby, to others and of course, still to myself.

So there is that.

But there’s also something about a career in the arts generally that we don’t tend to believe in, and by “we” I mean our society at large. We happily consume movies, TV shows, books, art, music—we understand that they are all created by real people who have received training and practiced hard. But if someone we know is pursuing these things (especially if they've yet to break through and have work sold) we are likely to consider it a hobby rather than a vocation.

I don't actually think the problem lies in some deep-rooted American cultural disdain for art. Yes, we don't fund it or teach it nearly enough, but I have yet to meet anyone of any political leaning or cultural background, who doesn't enjoy some kind of art. They might love Johnny Cash or Tom Jones, or they might love Taylor Swift or Beyoncé. Maybe they love Bruce Campbell films, or have memorized Gladiator, or have strong opinions about Korean soap operas. Point is, they love some kind of entertainment, and appreciate it as a form of art (they recognize there is something about its crafting that makes it superior to other films or songs. They feel these things add real meaning and beauty to their lives.

So we have a hard time believing that an ordinary person that we know can actually do these things, at least not well. Our suspicion is rooted in a deep admiration for art. It isn't that we think art is stupid or worthless. It's that we don't believe that the people who create it can be ordinary. We stan them into legends, call them Queens, worship them as if they were goddesses. We love their art so much that we need them to be somehow other than, greater than.

And so certainly then, we who see our own mere mortalness up close, might have a hard time believing that we really are artists. That we can make great art. It sounds pretentious as hell even to say that much. We, especially, who love it so much that we're driven to try and make it ourselves.

What’s most ironic to me is that if there’s anything superhuman about the writers and artists I know, it is that they’re patient and they persevere in the face of all this internal and external doubt. I think the difference between a regular person and a genius isn’t a genetic gift or a holy talent—it’s just about a hundred thousand hours of hard work and dedication. If there’s anything godlike about a great artist it is, I think, mostly the ability to keep on doing all that in the face of indifference.

George Saunders, in his essay “My Writing Education: A Time Line” leaves a six-year hole in between his leaving his MFA program and the publication of his first book. During this time, he remarks, he is struggling to raise a family, writing ad copy for a boss who calls him “George man” and coming to realize that he is probably the only person who cares if his life continues to have anything at all to do with writing. He describes this simply:

“I am trying to write at work but have begun to realize that, not only will the world not mourn if I never write again, it would actually prefer it.”

But at least, you may think, once you’ve been published, this whole thing must go away? Surely if you’ve had work accepted by an editor, or won a prize, or gotten rave reviews… surely then you don’t have to keep going around saying “I’m a writer” over and over again to combat your imposter syndrome?

Unfortunately I’m here to tell you that you probably will. Every new project will still feel like starting from nothing. Every past success will still feel like a lucky break, a mistake someone made. Every future idea will seem hopelessly impossible.

Think back to the high-achieving women in the first imposter syndrome study. No amount of external validation can erase it. If anything it may amplify it, because instead of skepticism, some others now have big expectations. You fear all your best days are behind you. You’re all washed up. You can't even remember how you did it last time. Meanwhile most people will continue to treat you as if you simply have a very peculiar hobby.

Once I was doing a radio interview and the host introduced me in their remarks as a “prize-winning author.” I didn’t say anything in that moment, but later I moaned to my wife that someone would hear it and judge me for not having stepped in to correct the guy that I had only gotten an honorable mention for the prize and that I wasn’t actually a winner. My wife looked at me incredulously and then calmly reminded me of two other prizes that I had actually won for my writing—but of course my imposter syndrome had happily papered right over them both in my mind, leaving me only able to think of the prize I hadn’t actually won (as if coming in third for a national prize was somehow a pathetic showing anyway).

I can’t explain it. I wish I could. I’m not a very insecure person generally at all.

But the same thing happened again to me not a year later, when a colleague referred to me a bestselling author. “Oh no,” I scoffed, “I wasn’t ever a bestseller.”

No, but I was, they reminded me—they’d been on my tenure committee and had spent a long time scrutinizing my CV. He reminded me that my last book in France was on their bestseller list, and that I was also on a regional bestseller list before that. Of course I was just thinking of the NY Times Bestseller list and nothing short of that felt real at all.

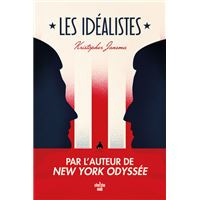

This week, I have a novel coming out in French, Les Idéalistes, that was never sold here in the US in English. I’m still hoping that it will be, but in the meantime I’ve been torn as to how to deal with the situation.

Most times I feel an inclination to just avoid talking about the new book at all: on social media or even with friends and colleagues, because it will only cause others to ask why it isn’t in English as well. It can only bring up my “failure” (which it isn’t) to get it published here.

Why isn’t it being published here? It isn’t because I wrote a bad book, of course—the readers in France are responding to it well already. My editor there read it and believed in its potential. Many others there did and agreed with him. I don’t have a fiction editor here at the moment, but the people who did read it weren’t confident it would fly in the American market. (The book is about American politics, something the French are very interested in but which editors here seem very skeptical we'd want to read fiction about.) This is all sort of complicated and hard to explain, which leads me to assume others will just naturally think, “Oh the book must not be very good then,” when of course that’s not the case at all.

Here’s another data point: my last book sold about ten times as many copies in France than here in the US. When that first happened, my initial reaction was to think that the translator somehow improved my prose and made the book better in that language than it was here. But of course that’s crazy—a bad translation can certainly sink a great novel, but I don’t think a good translation can surpass the original. The book got strong reviews there, but it got many here as well.

In the end I think it came down to people in France being more excited to read a novel about New York than people in New York (or the rest of the US) were. My subject matter was just more exotic there than here. The book itself didn’t change. There may be other national/cultural tastes that differ between French readers and US ones, but even then, that isn’t a reflection on any inherent lack of quality to my work. Again, I firmly believe that if an editor were willing to give my new novel a chance here, people would love it just as much as over there.

Still I have to walk myself through these thoughts over and over and over again. It begins to feel like I’m lying to myself about these truths, rather than accepting the imposter syndrome lie. It’s just so much easier, so much more immediate, for me to simply think, “Here they know I’m a huge failure and over there I’ve just tricked them or gotten lucky.”

I take comfort in the fact that other writers, wildly successful in my own eyes, have revealed in times of honesty they feel the same thing, even after winning even bigger prizes, or making even more impressive lists.

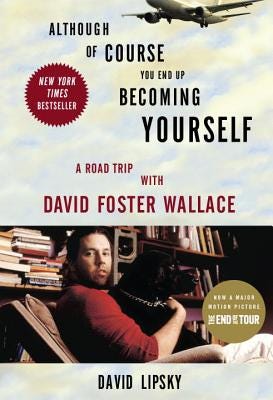

When I’m feeling particularly lost in my imposter syndrome, it helps to read these interviews, and to see what fragile messes my heroes all seem to be as well. There are so many instances of it in the book-length interview between David Lipsky and David Foster Wallace, Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself that I can’t choose one here to quote. Lipsky’s begrudging admiration for Wallace is defused repeatedly throughout the hundreds of pages of transcripts of their road trip together, when he finds Wallace’s insecurity running rampant at all turns.

This dynamic is very well captured in the film adaptation The End of the Tour. The egoistic Lipsky, a struggling novelist himself, reads Wallace’s Infinite Jest while consumed with jealousy, and goes to interview Wallace out of some mix of idol-worship and a wish to expose him as a bandana-wearing affected fraud. Only to find in meeting Wallace that he’s hard-working, fragile, thoughtful, humble, and above all else, very very patient. He wears the bandana not because of some “social strategy” but because he sweats a lot out of nervousness and anxiety.

“I’m so nervous about whether or not you like me,” he confesses to Lipsky at one point.

At another point, Lipsky points out that Wallace’s sales are unexpectedly good and that reviewers seem to like the book. (External validators are strong). In New York Magazine Walter Kirn has declared that the prize committees may as well give up now—the awards envelope has been sealed for Wallace. Lipsky asks Wallace what he thought.

A long time ago, I heard someone on NPR interviewing the comedian Margaret Cho about her success. She responded that the hard thing about winning any award is that by the time it happens to you, you’ve already seen a dozen people you really dislike win it before, and so it feels less meaningful than you thought it would initially.

There’s something to that, as hard as it is to swallow. Each time we see something else lauded for what we assume are bad reasons, it lessens the impact of whatever praise we get ourselves. It becomes just one more way we manage to push away whatever external validation is out there coming at us.

Recently I’ve been absorbed in the new book of critical essays by Charles Baxter, Wonderlands. It’s fantastic, and one of those reads where every single piece in it feels like exactly the thing I’ve been looking for. One piece called “All The Dark Nights—A Letter” is something I’d assign as required reading to any writer, anyone who knows a writer. I wish everyone in my own immediate circle would read it because it explains all of this so much better than I can, though I’m trying here.

Baxter has, in the essay, a bit of a long dialogue with Rilke, who wrote the famous Letter to a Young Poet which is often still given out to would-be artists. Baxter feels that Rilke’s example, however, is “absolutely unfollowable” by anyone—he describes a kind of pure drive towards art, a free giving-up of other life things, in the pursuit of artistic genius.

Baxter describes, in counterpoint, the “long dark nights of the soul” that he has experienced, repeatedly as a writer (and one who has been externally-validated all over the place for decades now). “Feelings of inadequacy are the black lung disease of writing,” he remarks. “Part of the deal with having a soul at all includes the requirement that you go through several dark nights.”

He notes that imposter syndrome is endemic in all the arts, but acute for writers because one’s “clear evidence of talent” is even harder for others to perceive than in performance, art, or music. Ironically it may be the egalitarian nature of writing that builds to this. “Not everyone has perfect pitch, not everyone can carry a tune, not everyone can draw or create an interesting representation of something on canvas. But almost every goddamn moron can write prose.”

This rings so true it kind of hurts. Baxter reminds us that this is perversely a key part of why we really are writers, and not imposters. He quotes none other than Thomas Mann who said, “A writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.”

So how do we get out of this? Is it just an inevitable struggle that we can never surmount?

Baxter thinks that it is, in some ways, something you can’t outgrow or get past for very long. Ever. If you did, you'd have lost the soul that makes you good. If it stopped being difficult, that's when you'd be the fraud.

Which is frustrating, but perhaps it finally lets us know that we shouldn’t allow it to distract us or derail us.

Another thought is that we can take those fears, the same as all our other fears, and turn them into art. The same way that I've written stories about my fear of rejections, I've written lots about feeling like an imposter.

My first finished novel was my MFA thesis, a YA book about two boys at a boarding school who invent an imaginary dead student to build a secret society around. The book was called The Liars Academy because the protagonist is a scholarship student who has convinced himself he's somehow been admitted to Colby Academy by mistake. He deeply admires his roommate Bradley, who lies effortlessly all the time with no guilt or anxiety at all. The book was born out of my love of literary and cinematic imposters and con artists like Tom Ripley or Frank Abignale Jr. of Catch Me If You Can. I've long loved characters who were faking it, and winning (for a while anyway) because it was how I felt as well.

My first published novel, The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards, continued many of these same themes. The protagonist is a writer who lies about who he is to everyone all of the time, who befriends an unstable “genius” writer and leeches off of him. I'm not sure how aware of it I was at the time, but looking back on it now I see clearly that I split myself into two possibilities. One, a liar and a fraud. Two, a “real” writer, though one who falls apart--not because great art requires madness or anything that romantic (and wrong) but because he works at it so intensely that he ceases to care for himself in basic ways. These were the two ways I could imagine success at that point: sacrifice to the point of insanity, or tricking everyone somehow.

In the end of the novel it is only by collaborating that the two writers succeed in finishing a new, great work. It's telling to me that I didn't see this originally, because it wasn't clear to me at first what I was doing. Originally the book ended before the collaboration, with the liar-writer coming to rescue the crazy-writer who is unknowingly stuck in an abandoned writer’s colony. It was only later that I realized the true ending of the book involved them coming together into one writer.

That novel resonated with a lot of readers who loved writing, and I suspect they felt what I did, a deep uncertainty that they'd ever succeed as writers. That it either would cost too much, or that they were somehow fundamentally unable.

Ironically, it was exploding that exact fear of my own that led to that book being written.

Coming back to that original study of imposter syndrome again, the psychologists did conclude there was a treatment for the phenomenon. They found that gathering the high-achieving women together in groups to discuss their feelings was effective in helping them to overcome those doubts. Seeing that they weren't alone in their imposter fears was successful in getting them past it. To that end, I think the more we can open up about our doubts, our dark nights of the soul, our Darkness Nexus, etc… the better we'll all be at getting out of it, at least until the next time around.

Until then, keep writing and have fun!

Illuminating as ever, Kris... et félicitations pour la parution! :)

Jody - Thanks for the close and thoughtful read! I'm thinking here of "writer" as someone who writes but is also pursuing the publication of that writing, and I agree that isn't true for all writers at all. Many write and never share that work beyond a few friends, and others might self-publish in some way or another (like I do here!) rather than deal with the world of editors/agents/submissions/etc. Nothing wrong with that at all! For me the distinction between "writer" and "author" comes between when I'm doing the actual writing work and then, in author-mode, shifting into that publishing/publicity phase of the process, where I'm now focused in some way on "selling" my work or even selling myself (doing self-promotion) in order to bring my work to a wider audience. It's worth a whole other newsletter post sometime for sure!