On Rejection

How much can we take? Is there any way to take the "sting" out of it?

In my final workshop course in my final semester of college, we had an alumnus visit to tell us about life as a working writer. I don't recall his name but he was maybe thirty, living in the Bay Area. He was finishing his first novel, he told us, and submitting lots of short stories to magazines and getting lots and lots of rejections.

The guest speaker told us that this was important, that we should aim to get a hundred rejections a year. We had to build up our tolerance. It would take the “sting” out of it.

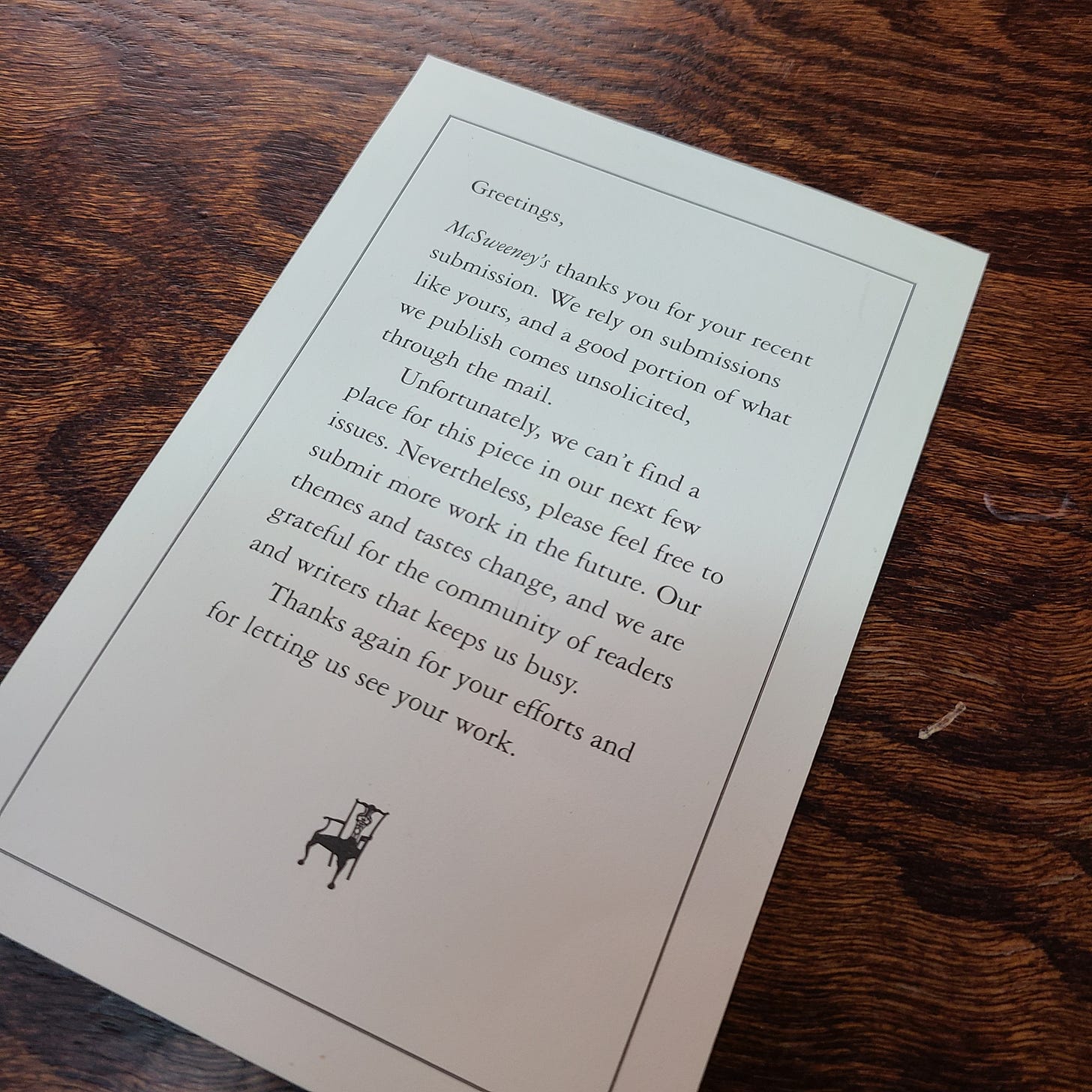

Later, he also said to only ever submit work to The New Yorker, the Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s, and (this was controversial) the then-newish McSweeney's Quarterly Concern run by Dave Eggers.

I didn't see how exactly I would rack up a hundred rejections submitting to only four magazines… I'd only written one short story I thought was even maybe good.

Our workshop that semester was twelve Senior fiction writers plus a small dog that one girl kept bringing for some reason. The professor turned a blind eye us to having wine and liquor in class. He ignored it until one day my roommate brought in some Scotch.

“Who brought the Chivas?” the professor said happy, as he poured out a cupful.

At the time this all seemed very grownup. We were all writing novels. Well, some of us were writing novels and some of us were starting a new novel each week. But we were surely almost there.

Surely, we were all very nearly real writers.

The guest speaker's next big piece of advice was to utilize the also newish technology of email to our advantage. (This was Spring 2003). We should keep an email list, and pass around a sign-up sheet at every reading we did at bookstores and coffee houses, so that we could later inform our fans when and where to come see us again. If we did that, we could build up a following and… well it was never totally clear what we were supposed to do then, because the poor man began to weep openly in front of us all.

“Sorry. It's just so hard,” he moaned.

It was memorable. (I worked a fictional version of this episode into my first novel.) I was mostly embarrassed for him, there in the moment. But looking back now, I can at least say I was duly warned.

It may have been the greatest moment of honesty in four years of workshop.

Because, nineteen years later, I can report that wow, no lie, it really is so hard. Every day I respect that poor guy a little more.

I had, back then, not yet started sending my work out. In four years of college I had finished just this one single story that I thought was good, and with it, I had applied to eight MFA programs. All of them had rejected me (including the one at my undergrad university)… except one.

The professor who called me from Columbia broke the good news over the phone by saying, “Not everyone agreed you were ready, but it doesn't matter. Congratulations!”

Ready or not, off I went. And I resolved to start sending out my work, just as soon as I had more work to send.

In Stephen King's craft book On Writing, he described starting his own writing career by taking a long nail and putting it through a bit of wood, then serving his rejections to the spike. I decided to use a regular push-pin on a corkboard, but still, it seemed like progress.

I also got subscriptions to The New Yorker, Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s… and McSweeney's. I figured I had to know what I was aiming for.

Nineteen years later, I've still never been published in any of them. But I did amass a nice stack of rejections from C. Michael Curtis.

I did enjoy the stuff in McSweeney's, when it wasn't too weird, which it mostly was. The stories in the other magazines almost never held my interest then, but I tried every week to care about them. I was 21 years old and just couldn't connect with the world or voices these stories were written from.

Still I submitted my stories to all but the New Yorker, because by then someone had kindly informed me that they really never publish unagented work. I'd also learned that there were dozens of not hundreds of other places to send my work. I got a giant copy of the Writer's Marketplace Guide, and got to work on racking up those rejections. I entered contests, I submitted for open calls, and I waited, literally by the mailbox.

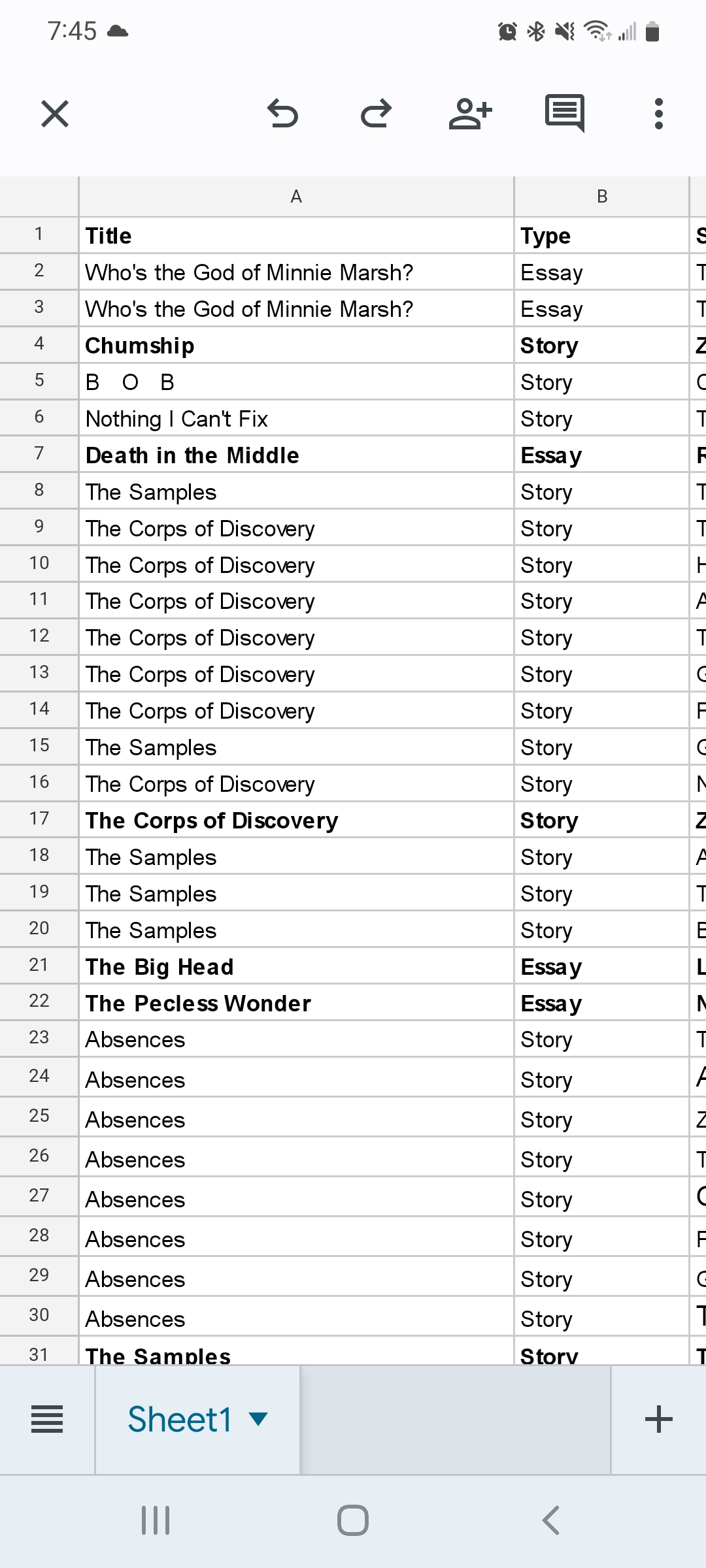

These days I miss getting my little rejection slips in the mail, returned to me in my own self-addressed stamped envelope. Occasionally they'd be hand-signed or with a little personal note; I collected them. I miss stacking them up on my corkboard. So much more satisfying than typing “Pass” into my spreadsheet:

Since I began tracking my rejections electronically in 2008, I've tallied 170 total submissions (this is just short work, essays and stories) and 21 acceptances. That's not bad, really.

But it means there were 149 rejections. It's still “no” about seven times as often as “yes”.

(I got another one just now, as I was writing this post! Hello #150!)

And, again, this is after two decades of writing. If I added in all those earlier rejections from 2004 - 2008, I'm sure the numbers would look a lot worse. (And if I added in agents and now novels… way way worse.)

Today I am glad many of those early stories never got published (they were not good) and I am glad that I got used to the disappointment, just as the guest speaker had said.

In the end it was getting all those rejections that started to make me feel like a real writer at last.

The final bit of advice we got from the guest speaker before he began weeping: he said that when anyone asked us what we did for a living, we should always say, “I'm a writer” or at least, “I'm a writer who also works at Starbucks,” but never, ever, “I'm an accountant who also writes.” We needed to boldly remind ourselves and the world what came first for us in this life.

I found this incredibly cringe-y, bordering on obnoxious. It reminded me of an episode of The West Wing where, after losing a bet, Toby has to go around for a full day in rural America saying, “I'm Toby Zeigler. I work at the White House,” whenever anyone asks his name. As you might imagine, people respond with suspicion, if not outrage.

This was, in any event, how I felt back in Senior year, when one of my friends began insisting on introducing himself as, “Hi, nice to meet you, I'm _____, I'm a writer.”

This usually got a response of, “Uhm. But aren't you, like, a college student?”

That friend, by the way, is not writing anymore. He published a number of incredible novels, but life has led him in another direction now. The same thing happened to the other writer I was very close with then, and who I would have then bet all my little money, would by now be very famous and successful. He wrote a wonderful novel, had terrible trouble selling it, got frustrated and vowed to never write again without getting paid up-front for his time. I respect that, but it isn't capatible with a life as a fiction writer, so that's that.

As far as I know, none of the other twelve students (or the dog) in that final boozy workshop group is still writing fiction today—though my roommate who brought the Scotch writes and edit tech reviews and probably gets more words down a day than I ever will.

I have no idea if the guest speaker is still writing, but I have my doubts. Even Professor Chivas Regal is now retired. I hope he’s still writing, but I don’t know.

When I look back at all of the classmates that I was most intimidated and impressed by as a younger writer, there are very, very few still at it. (Most are doing things they enjoy much more now, and I’m glad for them.)

Please believe me, this doesn't give me any tingly pleasure of schadenfreude. In fact it massively bums me out, because I sorely miss the company, and it reminds me of the narrow odds. Thinking about it only makes me feel like I am always surely next.

Back then I definitely thought that rejection was something you only had to deal with until you found an agent and sold a novel. I assumed, once you started to publish serious work, places would start calling you looking for work, offering money and honors from all around. (I thought this despite all the obvious evidence to the contrary.)

One night, with some family friends, I went out to dinner with a very successful writer who had just published her third novel. “It's all much easier after you sell your first book and get an editor,” she assured me. (She may still be writing now, but I think she's moved more heavily into humanitarian work.)

It would take me about six years to sell my first book. In that time I wrote three other books and had three other agents and got lots and lots and lots and lots of rejections.

On the day I finally sold the book (really my fourth agent did), I was convinced it wouldn't work out. I went out golfing just so I wouldn't sit at home going crazy waiting to hear. I wrote another essay about this before but I was certain that, once again, we'd come up short.

After all, when I had first tried to find an agent for my the novel, I had gotten turned down by a dozen people. They often liked the book, but didn't think they could sell it. “Editors have an allergy to books about writers,” one told me. “I think your book would send them into anaphylactic shock.”

Another agent wrote me a four-page email saying all the things they loved about my book, and then concluded that it was just a bad time for them personally and so they had to say no.

Eventually I found an agent who wanted to give it a chance.

The same thing then happened with all the editors as my agent tried to sell the book. Everyone said no. That people would never read a book about writers. One editor wrote me a long letter explaining a huge revision to the novel he wanted me to make, but without offering to buy it or even to read it again if I were to make the changes. I was willing to do the work, but I deeply disliked the direction it would have taken the book so I decided against it.

And then, while I was out pretending I know how to golf, one editor said yes. And that was that.

Funny thing about rejection. You only need one person to say “yes,” and once they do, it doesn't matter how many said “no” beforehand.

A week later, I found out that this publisher had resold my foreign rights in two other countries for even more the advance they were paying me. The book had gone from being a potential dud to an international hit in just under ten days.

That book went on to sell well, won awards, and was ultimately translated into six languages… I still get a royalty check from it twice a year, and hear from readers all around the world who love it and are inspired by it.

All of which I really am not saying to gloat, but just to back up my claims that all those rejections I got beforehand were not actually a measure of the book's inherent quality.

That's not really what a rejection is, as it turns out.

Every “no” I heard was based in someone's taste, someone’s mood that day, on someone’s assumptions, someone’s preferences… editors have to guess what will play in the market—a year or two or three in the future. They have to think about what booksellers want, and how it will be “positioned” in stores and in marketing. Editors have to deal with what their bosses like, or don’t like, and what marketing and publicity directors like and don't like, and if there is even one voice on an editorial board who doesn't love the project for any reason… it can mean the editor won’t get the support to buy it.

Often they are just as heartbroken as the writer (trust me, I'm married to one.)

It’s so hard.

But, the key is, no one in all those rejections was trying to tell me I was a horrible writer—even if that's what I perceived each time. They just didn't know how to publish it. Until someone came along who did.

Anyway, was my famous dinner companion right? After that did it at least all get easier?

Nope!

After that first book was published, my editor told me everyone there considered me a “house author” whose work would be published there for my whole career. Sounded pretty good to me. I hoped to never go through that rejection meat-grinder ever again.

I did sell my second novel to that same editor, but then right before I turned in the first half, she called to tell me she was leaving the company. I was assigned a new editor, and now he has also left the industry. I have been, in publishing world terms, “orphaned.” It happens all the time.

In the meantime my publisher changed leadership, was merged with another publisher—today I don't really know anyone there from even just six years ago when my last book came out. Meanwhile my agent moved to the West Coast and began shifting out of the industry as well.

I found a new one, and kept going.

It’s just the way it goes.

Now I'm back out there again, looking for love in all the wrong places, which is to say, writing new books, and trying to sell them, writing stories and trying to place them, and getting rejections for my (virtual) corkboard again.

It's so hard.

But—I have discovered one thing that makes it a bit easier. A lot easier, in fact.

I'll explain.

When I was on a book tour with that second novel, flying around the country on the publisher’s dime, doing readings every night in different cities, I wanted to feel excited and accomplished and good.

But mostly I felt nauseated and anxious and scared. By the end of the week, I was sweating so much that the skin on my palms and fingers was literally peeling off.

What was I so worried about? The book had gotten strong reviews. People were showing up to the events. And yet I couldn't help myself from panicking. I tried to really think about what I was scared of. It wasn't fear that people wouldn't like the book, or that I somehow wasn't getting enough attention. I enjoyed being on tour not because I enjoyed the spotlight, but because I enjoyed meeting people and seeing them enjoying the book. I like knowing I’ve made them happy, shared something valuable with them.

And that was happening, so why was I freaking out?

Then at some point it hit me, that I was going crazy because I was convinced that if things didn't go well, I wouldn't be allowed to do it again.

And by “it” I don't mean go on a big tour and stay in nice hotels and eat room service (none of which I was enjoying much since I was so panicked). By “it” I just meant, “write another book.” Because I loved writing books, and because I want to spend the rest of my life writing books. Because, as my old friend the guest lecturer would have me say, I'm a writer.

Recognizing that helped, and it helps me now every time I begin to feel that “sting” of rejection or fear failure. Because here's the thing. A publisher, an editor, an agent, a critic, another writer, a reviewer… none of these people get to decide if I'm allowed to write another book.

They don't decide if I am a writer or not. All those other people have considerable influence over me getting my work published and that's obviously important. But the only person in the world who gets to say, “you're not allowed to write anymore,” is me.

Look—I said it before. Most of my friends who don’t write anymore are happier that way. If I ever find something I love to do as much as I love doing this, maybe I will do that instead. But I haven't yet. And I've found a lot of other stuff I really love doing. Just not as much as I love writing.

I just love it.

Love making sentences, love words, love stories, love characters, love to twist a plot. I wake up early to sit in the dark on my couch and write for an hour before my kids wakeup. I write on my phone in the shower sometimes, I can't wait ten minutes to finish drying off. I love puzzling over it all, making it better and better. I love sharing it with other people. I just love it.

I'm a writer. On that level it doesn't matter how hard it is. Even if I knew I could never publish another book in my lifetime (and how could I ever know that?) I'd still write them. Line each one up on my shelf and go on to the next.

Maybe you feel the same way. Maybe you aren't sure if you do. That's ok! But just hear this: nobody else gets to tell you it is time to stop. Nobody can tell you that but you.

That, I think, is what we really mean by taking the “sting” out of rejection. It means taking its power away, recognizing it is one opinion, likely not at all based on your work's inherent quality. Should we still try to work out where we might have gone wrong? Sure. We should and we must look for areas to improve, places to grow. But should we imagine ourselves at the center of some vast conspiracy of gatekeepers, trying to prevent us from succeeding? I don't recommend it.

I have students who, having written a few drafts of a few chapters of a book, want to know if they need to change their names because they're too generic and won't make a good brand. Or they're panicked that because of what they write about, or worse, who they are, that no publisher will consider their work. I'm amazed at how many reasons they can invent to not even try--but then I remember that it must be easier to tell oneself, “I wanted to be writer but some cultural conspiracy made that impossible,” than to keep doing the hard work, never knowing what it will amount to, personally or professionally. That is, to just say, “I'm a writer.”

Rejection feels like someone is telling you, “your work is bad,” or even, “you, personally, are bad.” But having been a judge on contests, for statewide grants, reading for graduate admissions, and even selecting things for the school literary journal… I know that's not the case. Sure, sometimes you find work that is truly bad on its face, but that's pretty rare. Mostly it is not fully polished. Mostly it is not fully developed. Mostly there is a lot I like about it but I liked something else even more. Mostly it is perfectly good but just not interesting to me specifically. Judging art is nothing if not highly, highly subjective. But almost never do I say “no” because I actively dislike the work, and certainly never because of who the writer is personally.

All of which is to say, rejection sucks, of course, but it is also less related to you or your work than it feels.

Why does that matter? It's a rejection either way, right?

It matters because a rejection isn't a STOP sign. It's just a roadblock, and there are other roads. The only one who gets to say STOP to you, is you.

Frustration and rejection aren't unique to the literary or artistic worlds. Your friends and neighbors face them in all kinds of jobs, in looking for new jobs, in trying new hobbies, in trying anything new at all. In most other walks of life, we think of handling rejection gracefully as just an ordinary part of life, or the work we do in life. So there's no need to think differently about failures when it comes to the Arts. We either push ahead, or we try something else.

Returning to The West Wing once again, I have made this one line of dialogue my mantra lately.

It's delivered by a consultant, Amy Gardner (played by Mary Louise Parker) after she loses her job at a nonprofit during a policy fight with her boyfriend Josh who works at the White House. He comes over to apologize for making her lose.

She rejects his apology.

“I loved my job, but when I lost it, I didn’t pitch anything. I didn’t stage a nutty. I fought you, I lost, I had a drink, I took a shower. Because that’s how it is in the NBA. You know what I do when I win? Two drinks.”

That's the energy to take with you. I'm sure as hell taking it with me.

Because that's how it is in the NBA. Even the best team in the league is going to lose a lot of games every season. (I think. I don’t really watch sports.)

Here's a closing thought from Edith Wharton's The Writing of Fiction, which I've been reading (for fun, in my miniscule free time… just one way I know this writer thing isn't going away anytime soon.)

“Whatever a man has it in him to do really well he usually keeps on doing with an indestructible persistency.”

If you're reading this newsletter in your little free time, for fun? Then I have a good feeling you have it in you too. So go do it with indestructible persistency. Tell people you're a writer. Tell them you got ten rejections on your pile so far, and just ninety more to go. It's so hard. But that's ok. Tomorrow you'll write something even better than you did today. As long as you’re still having fun, then you’re allowed to do anything. Anything.

And how many people get to say that about what they do all day?

But the good news is that you have a novel coming out in France in a few days :)

Thanks a lot for writing this. And I guess generally for writing. Somehow your writing is putting me into a better state. Not only because of the information, but also because of a "vibe," an atmosphere that exists even in these non-fiction posts.

This post made me think very hard. Why do I tend to write for myself and not even try to submit? Why I often drop a story just before final resolution? When I read "I wouldn't be allowed to do it <write another book> again." I felt my fears got explained so goddamn well! That's it. If there's a rejection it's an implicit order "you cannot write another word". It's good that this goddamn order exists only in my head. Or maybe it's actually bad: if this order was a part of a rejection letter, at least I would keep writing out of spite. On the other hand, maybe that's what I should do anyway.

Anyhow, what I wanted to say is "thanks" :)