Try, Try Again

Perseverance vs. Resilience in Creative Life

When a student asks me if I think they’ll ever publish their work-in-progress, the biggest “x factor” in my mind is not their level of talent or genius. (When I think back on the work I did at their age, how good was any of it really?) The x-factor is really whether or not I think they can keep at it despite inevitable disappointment and frustration, which, at least initially will likely be pretty lopsided.

Can they keep going in the face of indifference and rejection? Do they love writing enough that they won't be stopped by all the setbacks that will come?

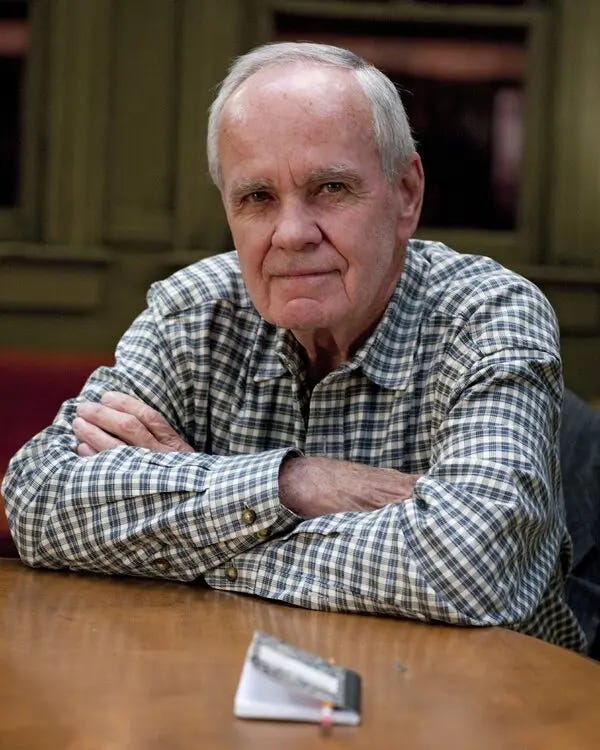

Lest you think I'm entirely projecting my own personal experiences here, consider the career of Cormac McCarthy, one of the greatest writers of the late 20th century, who passed away last week. As many of his obituaries pointed out (and to the surprise of many fans including me!) McCarthy started writing while he was serving in the Air Force in Alaska, having little else to do but read. He published his first novel in 1965, but it was a commercial flop, as were the next thing three (though he did win a MacArthur Genius Grant in there too!). He didn't write a book that sold more than 5000 copies until 1992, with All the Pretty Horses. That's just how it goes sometimes.

But how many writers are going to keep at it for 30 years, through five “disappointing” books? Not a lot, right?

We usually call this “perseverance.” I talk about it often as being the trait that is most key to success for a writer. But lately I've wondered if it would be better to think of it as “resilience.”

Perseverance is about one's ability to persist in attempts to achieve a difficult goal… to not give up. That's important. Resilience seems synonymous but isn't quite. It's an ability to recover quickly from difficulties, to shake off disappointment and failure. The first is about outlasting your challenges, muddling on through them, and finally winning by refusing to quit. It's about patience.

Resilience is not about endurance over time, but endurance over opposition. It's acknowledging that you're getting your butt kicked regularly, but shaking it off, bouncing back each time, and that success only comes through something closer to “toughness” than to patience.

There is a lot of overlap between the two ideas, of course. But the first is more passive to me, and the enemy is general. It's time itself. The second is active, and the enemy is specific. It's rejection, it's failure, it's blockades outside of yourself and blocks within yourself. It frames the struggle as a battle, as a conflict—welcome terms in storytelling—instead of a kind of stoicism.

In a perseverance framework, you fail when you give up. In a resilience framework, you fail because something else knocked you down (and you stayed down).

I'm a little wary of this idea (even if it's my idea) because thinking as a teacher, it seems to be exactly the thing that justified the worst and cruelest teaching I received: needlessly harsh criticism from professors, an “every man for himself” attitude about workshopping, making writing into a competition when creativity isn't a zero-sum game.

Reeling from a disastrous workshop, stung by the comments thrown around about my crummy story, insulted by sarcastic professors, I'd wonder if it wasn't done that way on purpose… to teach us to be resilient, to press on, not just regardless of the criticism, but in spite of it.

And didn't that work?

Hadn't that “toughened” me up, thickened my skin? Driven me to “show” the doubters? Hard to deny that it worked, but also hard for me to gladly adopt those same strategies now.

Many years ago, I posed a question to my own professor. Did he think I had what it took to be a writer? His reply was this:

“If you could be happy doing anything else, I'd say you should do that instead.”

Ouch. I took it as discouragement and I sincerely believe it was meant that way. And once I got over the sting, it truly pissed me off and made me work even harder. “I'll show him,” I thought…

But eventually I realized that it really is a pretty reasonable statement.

Because if there was some other thing that made me happier in life, why wouldn't I pursue that instead? The rewards of writing literary fiction in the 21st century aren't so financially compelling, and it's at least reasonable to debate if even *great* books can really change people. (I think yes, but it's a complicated argument, deserving of its own post someday.)

A creative career isn't like other ones. There are lots of reasons we do work that we don't really enjoy doing. But I don't know if anyone who becomes a writer because their parents pressured them into it, or because they saw it as a sensible path towards financial stability. Once in a while I'll find a student who truly believes that their fantasy novel will sell for millions and set them up for life, and most bail as soon as they see it isn't nearly that easy.

So again, why write fiction unless it makes you happier than doing everything or anything else? If I also really enjoyed selling vacuum cleaners, why wouldn't I go do that instead? I'd probably make a better living, work better hours, and I could feel good that I'm helping people keep their houses clean. But… I don't want any of those things really. I want to write fiction. Enough to want to get back up again every time I'm knocked down… and that's not an easy thing.

There's resistance, first off. My professor's “do something else?” comment wouldn't be the last discouragement I'd run into from mentors, strangers, and even from friends. Writing often means working the kinds of odd jobs that can give some flexibility and still help keep a roof over your head. Often it means accepting a crummy salary or frustrating work, and also tightening whatever belts can be tightened if it means you have a little more time to write at the end of the day. That was hard enough when it only affected me, but now it affects my family too. (And I'm incredibly lucky to have a teaching job that is stable even if I do wish it paid a lot better).

Our country, at least, is not particularly encouraging of people making art. We don't support it well, financially or emotionally. It can be a lonely and isolating path. It can create tension in relationships. I've seen it end marriages, estrange siblings, and even get someone threatened with disinheritance. It's never a benign path to go down, as much as I wish it were.

So there's an argument to be made that some “tough love” is required to prepare students for all that. That we do a far greater disservice to them by being gentle and supportive, because they are going to get stomped on out there. And I get that, I do.

Most success, particularly at first, often means sharing work with tiny audiences in some obscure venue, without much (or any) compensation. My first five or six stories took me years to publish, and each of those went to tiny websites and journals, none of which paid me a dime. But that's how I got a few credits on my cover letter so that the bigger places started to notice my submissions and then find an agent.

Most importantly, getting rejected over and over was how I began to get better. I've gotten a few reviews so harsh that they made me want to quit, but after the pain faded a little I was able to see that there was some kernel of helpful advice buried inside the critical diatribe that had been leveled against me. In one case I even wrote an email thanking a citric who'd absolutely gutted me. (They were cheerful and surprisingly grateful in response!)

It has taken a long time, but I've learned to be keenly aware of what parts of my craft will always need extra work. I know by this point that I'm not great (initially) at a few things in particular, but I also know that if I spend the time on them, I can compensate and revise and workaround and fix things as needed. At least writing has the benefit of being something you can perfect in private, so long as you are also resilient in the meantime.

It just takes a lot of time and a lot of faith, and not everyone is going to put up with all that. No shade to them. It's just not worth it, frankly, unless finally getting it right makes you happy enough to warrant all the bumbling and fumbling and grumbling along the way.

I’ve known plenty of talented writers who quit at the first real signs of difficulty, or at the hundredth, and it’s heartbreaking when that happens. Though I think most are happier now doing something less insane-making.

Perseverance means continuing to stubbornly push ahead on your work-in-progress, no matter how many drafts and rejections it takes. I've had stories I've rewritten six or more times. Novels rewritten even more. And rejections outnumber acceptances 10:1 even now (and often it can be more like 20:1). Being able to keep at it anyway… that's clearly key.

But then there's resilience, which sometimes actually involves… giving up? Because in all those draft folders are more than a few stories that I have rewritten a number of times and finally walked away from. After twenty years at this I have several novels in this same condition as well, plus huge parts of other novels I've cut and abandoned along the way. Quite often, the answer is to let go and start again with something else. To stare the sunk cost fallacy in the face and dismiss it, even if what it has cost is months or years of your time.

Sometimes resilience is about accepting defeat and moving on… and that isn't quite captured by the perseverance model.

I think the real answer to “Will I ever make it?” isn’t “Will you never give up?” but “Can you start all over again?”

It’s not what my students want to hear, and so I typically avoid putting it in those terms. They absolutely should push on and get to the end of their projects and learn everything they can along the way that will make them better for next time.

But then what?

I've thought more and more, as a teacher, how resilience can be taught differently than the ways I was taught it. Rather than beat my students up emotionally and see if they fight or flee, I want to instill resiliency in a positive way.

Fortunately, as a parent, I've discovered that this is a similarly huge area of concern. Parents I know are all asking how can we help our kids be more adaptable, less readily frustrated, but without resorting to the same kinds of “life sucks, just tough it out” messaging that was so common and so damaging when we were younger?

One that I like is to “Foster Confidence”… meaning to boost their faith in their abilities, without deluding them into believing they're already perfect. Another is to “Model Resilience” by sharing openly my own setbacks and failures, or those of writers they idolize (this is the main thesis of my upcoming book REVISIONARIES!). A next step is to use that honesty to promote Peer Discussions of failures and overcoming, and generally “normalize” the concept so that it doesn't derail a writer facing it later in their career. There is a lot more, and much I'm still exploring, but I'll end with a favorite… very much on point for this newsletter.

Make it fun. I remember as a kid, playing video games (which I was usually pretty bad at) and getting really pissed off when I kept dying over and over. Worse, if I was playing with friends it was even embarrassing, cause to be teased. But the best games made failing fun… in the Kings Quest games (and many other by Sierra) the death sequences were often funny, with gross animations and sound effects, that made the setbacks easier to swallow. Often I would seek them out intentionally, just to see what would happen if I did something obviously “stupid”. It was always pretty entertaining.

Getting rejections and bad reviews aren't usually very funny, of course, and I take writing seriously enough that I don't want to treat it like a joke or a game. It's ok to be frustrated by these things (feel your big feelings, we tell our son) but you definitely don't need to feel ashamed. Make a game out of it. Collect rejection letters, hang them up on your corkboard, remember that they are evidence that you're still trying, not evidence that you suck.

One thing I've enjoyed is writing stories about rejection, or about my perceived critics. Think about Tobias Wolff's classic story “Bullet in the Brain” where a snarky literary critic gets shot during a bank robbery (because he can't stop mocking the robbers). No way that Wolff didn't start writing that one with a particular critic in mind. In the end he turned that frustration into a truly beautiful (and hilarious) story.

Don't take it personally (chances are it really isn't!). Try, try again.

For my students this year I played a video of basketball player Giannis Antetokounmpo telling off a reporter who asked him if he felt liked he'd failed because his team had been eliminated in the first round of the NBA playoffs. He asked the reporter to reflect on his own career:

“Every year you work, you work towards something, towards a goal, right? Which is to get a promotion, be able to take care of your family, to be able to provide the house for them or take care of your parents. You work towards a goal. It’s not a failure; it’s steps to success. There's always steps to it. Michael Jordan played 15 years, won six championships; the other nine years was a failure? That's what you're telling me?”

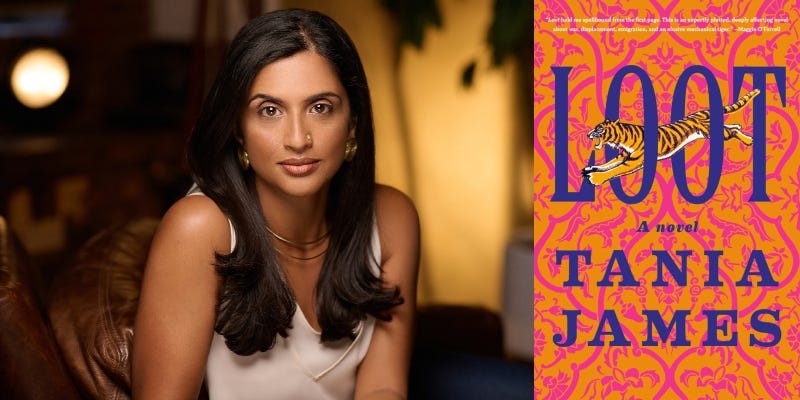

A former classmate of mine (always terrific in workshop, btw) Tania James, recently gave a wonderful speech about Joy and Failure and Play for the One Story Debutante Ball.

I highly encourage you to read the whole thing, and then to order her new novel Loot, which is getting amazing reviews and is sitting on my TBR as we speak.

James talks about being a debut author herself, and thinking she'd made it at last, as she met a random superfan on the street… only to realize that this reader actually thought that she was Jhumpa Lahiri.

Later James reflects on the long road ahead, the way she'd slowly learn the pleasure of “breaking up with” a novel in progress that isn't “giving anything back”. She realizes that there will always be long stretches of time in between publications where it feels like nothing good will ever come again. She notes, “The longevity of a writer depends less on each individual book or story, and more on how you move through those stretches of nothing special.”

This is crucial, and informs another dimension to creative Resilience. Often you're in conflict with external forces, but much much more often you're just in a sort of holding pattern, where nothing's turning into something fruitful. You have to return to patience and Perseverance again. James advises us to see these times as our opportunity to play around. To do stuff that won't lead anywhere clear, and to get back in touch with the fun of your work. And the fun of failure, that is, of “playing the game” that as she puts it, “never ends.”

I think about Cormac McCarthy, trying to amuse himself with some writing, while stationed in an Air Force base in remote Alaska. His final two novels, The Passenger and Stella Maris published just last year, didn't exactly get huge praise from the critics, but I bet he didn't care very much. They seem to confound many readers with their un-McCarthy-like focus on science and philosophy. But to me that is the greatest success. Right up to the end, he was trying something new.

That's what it's all about.

Outstanding! The basketball video— priceless! Thank you.

“If you could be happy doing anything else, I'd say you should do that instead.” This is something I say to aspiring cartoonists, too. In fact, I often say it’s unfair to do anything else— unfair to those who can’t do anything *but* cartoons/art/writing. For goodness sakes, leave it to them and be happy!

After finding out my agent had not even looked at the first draft of a novel I sent them almost four months ago, I found myself saying just yesterday, “nothing gets me down tho god only knows why.” I had spent those months thinking intensely and critically about what I had written and also realizing it might have been unfair to send them this book (but had to, out of deference to our agreement), because I just didn’t think they’d know what to do with it. I think I need an agent or editor with my Latinx American background, or who at least studied the subjects I’m addressing.

So, I feel like every setback has created more insight and understanding in me, and really the only thing I’m afraid of is getting hit by a bus or crushed by a random asteroid before I finish it and find the right editor.

What keeps us going? Who knows? But we are blessed, I think.