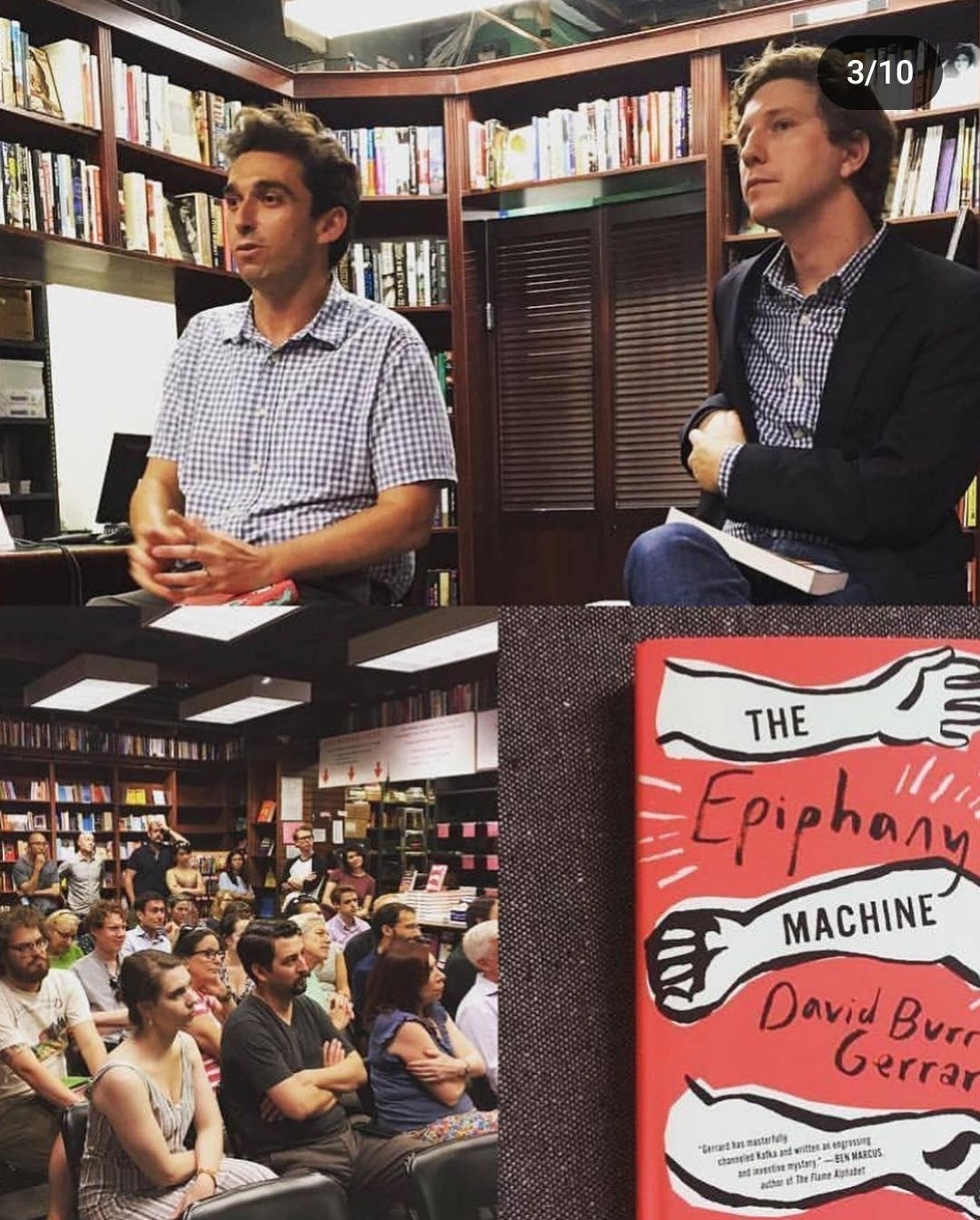

A few weeks ago the writer David Burr Gerrard died unexpectedly at the age of 42. He was my friend. We were at the Columbia MFA a year apart, but never knew each other well back then. We became close on social media, at first, and later did a reading together on the Upper East Side when his novel The Epiphany Machine came out.

The more I got to know him, the more I realized that our lives intersected in odd ways—a college friend of mine had been his closest friend in a high school writing workshop. Then, a childhood friend of my college roommate’s was David’s college roommate. A former undergrad student of mine ended up taking his post-grad workshop. I’m someone who likes coincidences, and is inclined to read higher meanings into them. David, I don’t think, would have. He was just one of those people who connected a lot of different writers and people. Someone who you met once and didn’t forget. Someone who popped up, often, because he was so deeply engaged in this community.

After his daughter was born, David and I became neighbors, sort of—he lived just across town from me—and we’d often bump into one another at farmer’s markets, the library, the coffee shops, and playgrounds. We talked often about the challenges and joys of fatherhood. Like me, he was a dedicated teacher of creative writing. He worked at Manhattanville College just after I’d taught there, and then later at the New School and for 92Y. We’d talk all the time about our classes, what we were assigning and how workshops were going (or not going) and of course—David was an incredible writer, and a sharp reader and editor, and I was lucky both to be able to get his eyes on my stories and novels, these past few years, and to be able to read his works-in-progress.

These past weeks, since his death, I’ve opened up the various works he sent me, delighted to be able to read over rough drafts of short stories and pieces of a third novel he was working on. His voice, his warmth, his humor, still exists all over those pages and in the pages of his first two novels, Short Century and The Epiphany Machine. You can read more of his short fiction and essays through the links on his page here.

David was such an inventive, funny, thoughtful and kind writer, and I’ll miss our monthly commiserations over the often chaotic and sometimes brutal publishing industry pressures that we both occasionally found ourselves wrapped up in. He was a good listener, and a good role model. He was one of the reasons I decided to try getting off social media and break up with my phone a few months ago—because I’d seen what a good impact the same thing had seemed to do for him. He kept me honest, kept me on track with writing, but also with my own self-care. Seeing the impact of cutting back on drinking, and stepping up exercise, had for him, got me to do the same last year.

Maybe one of the things I’ll miss most is that we texted each other photos of funny vanity license plates that we spotted around town. Here are a few recent ones:

I often joked that we should add them all up into some sort of funny McSweeney’s list or something, but he never seemed interested.

There was something nice about it being something amusing to do together that wasn’t somehow related to writing.

I’ll miss David a lot, and I know I’m not the only one who will. At his funeral I bumped into at least a dozen other writers and literary types who’d made the journey up to say their farewells and mourn the loss of a great man, a great father, a great writer—a great friend.

Starting to write this, I intended it to simply be some sort of tribute to David, but as I thought it through, I realized that it has all been causing me to reflect on literary friendships more broadly. Losing such a close ally in this life as a novelist has left me feeling a familiar impulse to withdraw—to pull away from other writers and friends in some knee-jerk self-protective way. (Maybe the only good thing that comes out of having lost far too many friends and mentors, not to mention a sibling, is that I do finally have some self-awareness of my reactions—thanks, therapy!)

But I remind myself that withdrawing into some kind of reclusion mode isn’t the answer.

I’ve always had an odd fascination with recluses. One of my first literary idols was author JD Salinger. I taught a class once on “Famous Recluses” and had students discuss Salinger, Dickinson, Thoreau, Michael Jackson, Syd Barrett, Harper Lee, Thomas Pynchon, and others who somehow existed at this nexus of solitude and fame. It always intrigued me. The mystique, the mystery. The having-your-cake-and-eating-it-too. The way it seemed to argue for the invisibility of the artist, and of letting the work speak for itself.

What I found, again and again, was that most of these artists prized their privacy and solitude, but that usually there was something darker at work as well—most were struggling with mental illness or responding to traumas—the closer I looked at it, the romance of reclusion began to disintegrate and even seem frightening.

Perhaps out of this same fascination, my own books and stories often revolve around literary friendships. I love writing about writers, maybe in part because I know I’m not supposed to. But mainly it is because—well, I love writers.

Not in the abstract either, but in a very specific way. I loved David, and I love so many of the other people I know because they love this same thing I do. Generously they allow me to share in that love with them. I think they’re fascinating. I think they are admirable, and complicated. They’re my favorite subjects.

“One is not at all free to write this or that,” opined the great Gustave Flaubert. “One does not choose one’s subject. This is what the public and the critics do not understand.”

I love to write about writers because they are seekers. They seek the things I seek. I don’t mean fame or bestseller status (although I’d take it) but some kind of deeper truth that we agree can lie at the end of this meditative and arduous and often lonely process.

When we get together at some coffee shop table and trade drafts, we’re doing so many things—from catching the smallest typos to addressing the biggest plot holes—but beneath all that we’re always asking the other writer, “Did I find it?”

Did I find the truth, with this?

We write because it fills us with the sense that we are telling truths (even as we fiction writers are, often, making things up) but then, in the end, we read it over and can’t really know if we did find it or not. And so we hand it off to someone else to see how we did. We need each other for that.

We need each other because this work is so hard, so alienating, so time-consuming. Because our other neighbors and our family members and even our best friends simply don’t want to sit and listen to us go on and on about the intricacies of the star-system at Kirkus and the importance (or not) of good pre-pub attention… or any number of other incredibly narrow things that only we really care about.

We need each other because, unlike so many other art forms, our work is almost entirely done alone. Painters and photographers and sculptors may work on their own, but often do collaborate with others too. And dancers, musicians, actors all almost necessarily have to work with others to produce their art. Even a playwright or a screenwriter is, usually, in some kind of collaborative mode with other playwrights and screenwriters, and certainly they know that if what they wrote alone is ever produced, it will be left in the hands of many, many others.

But fiction writers, poets, essayists—we nearly always work alone. Producing good writing means sequestering yourself for hours, sometimes days, at a time. This can go on for weeks, months, years. It can take us over, too much, sometimes.

At the same time, our goal is to share what we make. Our work is inward-facing, but the end product is outward-facing. Some would argue that a great story or novel or poem or essay has meaning and value even if no one else ever sees it. But most of us would agree that it takes on a much greater one when it is released. Other people bring more interpretations, find more truths, make more meaning. What we write can only ever really live on if they enter the minds of others too.

A mentor of mine once remarked (as a compliment, I’m sure) that I was the most extroverted writer he’d ever met. It’s true—I like being around other people a lot. I like being alone a lot too, but the work I do alone sometimes feels like I’m hanging out with friends in my mind, because it is other people that I love to write about the most. The writing I do about myself tends to rarely be the writing I like best.

An old joke goes:

“Why are the politics in the academy so bad?”

“Because the stakes are so low.”

I think about this often as a teacher, as colleagues will often find very dramatic ways to argue over incredibly small things that I can’t ever even begin to care about. To be sure, there are lots of writers who act this way too, and plenty of real, deserved animus out there. But there’s so much more generosity, so much more help—thanks to people like David.

I found workshops when I was younger to often be frustrating, because there was a real “winner-take-all” feeling to many of them. We were supposed to be competing over which of us was the best writer in the room, and who could earn the most praise or love from our withholding professors.

But even twenty years ago, I knew lots of writers who weren’t on board with this approach. “Workshop isn’t an episode of Survivor,” my teacher, Alan Ziegler once told us. “You don’t win by getting everyone else to quit and go home.” Instead, he advised, the best thing we could hope to leave our MFA program with was a group of friends whose work we admired, and who could be readers for us going forward.

He was 100% correct. Those friends, including David, have meant more to me, and have sustained these efforts, far more than anything I learned from a professor in a lecture or a seminar, and benefitted me as a writer much more than any critique I ever got in any workshop. Instead of fighting for the blessing of the authorities, so many of us became our own collective authority instead.

A recent article by Isle McElroy in Esquire, “The Rise of Literary Friendships” describes the shift that I’ve seen since the early 2000s:

in recent years, the bitterness churning through the literary world appears to have waned. While competition remains an inextricable part of a literary career—awards and end-of-year lists continue to pit authors against one another—it’s become more common to see writers rooting for each other. On social media, writers are just as likely to hype their peers as they are to self-promote: linking where to buy books, posting photos of readings, and sharing passages from galleys. Where once was envy is now admiration.

This new ecosystem is a departure from the reputation of writers being fueled by “unbearable envy.” And though this kind of support has been accused of being anodyne and false, I’ve gained a lot from having more friends than enemies. I am not an uncompetitive person (this is a generous way of putting it), but the frothy urgency of competition, I’ve had to accept, doesn’t make for good writing. It makes me miserable.

Gone are the days of Norman Mailer head-butting Gore Vidal, or of Ernest Hemingway trashing F. Scott Fitzgerald in his memoirs. Gone (I hope) are the days of Richard Ford shooting the book written by a reviewer (Alice Hoffman!) and then mailing it to her afterwards. Years later he also spit on Colson Whitehead over a different bad review.

Whitehead, a guiding light for the generation following, has largely brushed it off in public, rather than perpetuate the feud, advising others lightly to perhaps pick up a raincoat before they review anything further by Ford.

That’s so much more powerful than spitting, or headbutting back.

We aspire to heed our better angels, instead.

I remember a professor of mine telling us with savage delight about how he’d written an op-ed dissing Jonathan Franzen that was going to run in some newspaper, in response to some (perceived) slight against him… while it seemed pretty clear to me that Franzen almost surely had no idea who he was at all. It just felt like a huge waste of time and energy to me.

Didn’t he have a novel to be writing?

Twenty years later, I just don’t see much of this happening out there anymore. I agree with McElroy, this may be due to the rise of social media, allowing us to leap over the walls we so often throw up around ourselves. I think it probably helps in some ways that our antics aren’t really fodder anymore for articles in the Post or discussion on the Dick Cavett show. But I also think that my generation of writers, having grown up in the shadow of all that hostility and competitiveness, has made an intentional turn in a better direction. We’re conscious of the importance of banding together. I’d argue it’s more beneficial now to be seen as a “good literary citizen”—that being one is more likely to help you get blurbed, to get invited onto podcasts, to be asked to do events with other writers. Ironically, as the stakes have gotten smaller, and the publishing industry has contracted, we’ve built systems that promote good will and support.

But it goes beyond these big picture things too—to the most vulnerable moments in our writing lives. Because when the parties and the interviews and the twitterstorms are over, it is still just you, alone, with the work. You, alone, with the doubts. You, alone, bearing up as best you can under the weight of your own intense expectations for yourself. You, alone, seeking.

“The hardest part of being a writer is learning how to survive the dark nights of the soul,” Charles Baxter writes in his new essay collection, Wonderlands. He assures the reader that every writer out there has them, no matter how successful they might be. And he’s right, of course, and it is comforting to me to know that we all have them. That they come with the territory. Every sailor must be able to navigate through the bad weather, or they’ll never leave anchor.

When I think about David, I think about how often he was one of my first calls during these dark nights of the soul. I know I was someone he called for more than a few of his. And this, maybe, is the realest underpinning of the literary friendships we’ve all formed with each other.

It has to be done alone; you can’t do it alone.

You just can’t. Maybe this was why I admired Salinger so much, early on, because it seemed to me he’d found a loophole wherein art could exist without external pressure, entirely for internal pleasure. But it isn’t real—that isn’t how it works. Because when the dark nights come, you have to be able to pick up your phone and text someone who understands. Why you feel like the world is over because you’ve tangled up two subplots, or because you know your seventh chapter still needs work, or because you just read something that someone else wrote that’s so good it has left you in total despair.

Therapists are paid to understand, or to try to. Friends and family will, hopefully, at least pretend to understand.

But we’ll know they privately think we’re being irrational and melodramatic… which we are, we know that, it’s just that it’s very, very real anyway. We need someone who has been there before, who won’t dismiss a grammatical crisis when it descends on us. We don’t write alone.

The epigraph to my essay collection, REVISIONARIES (out next November from Quirk Books!) is a quote from one of the unfinished novels I’ve written about, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Love of the Last Tycoon.

“Writers aren't people exactly. Or, if they're any good, they're a whole lot of people trying so hard to be one person.”

The line is delivered by the heroine, Cecelia, the daughter of a Hollywood producer (after meeting a man at a party and becoming dismayed to discover that he’s a writer.)

It rings so true to me, and reflects both the many voices we all hear in our own heads, but also the many other people who surround us as we write and who contribute to what we are writing. It’s a reminder that we aren’t alone.

When I went to Princeton to read the working drafts of Tycoon, I read this line over and over, in Fitzgerald’s handwriting and then on his typed pages. In the folders with these drafts were also letters—hundreds and hundreds of them, usually many written each day, to his daughter, his wife, to Hemingway, to various other literary friends. He talks to his editors but also to his accountants and producers and random associates of all stripes. You see him bragging about how his new book is coming along well, despairing that it isn’t, worrying that he can’t get an advance, wondering if he has any talent leftover… it is sad at times, funny at other times, but always very relatable.

One of the best writers of the early 20th century, certainly one with his share of dark nights of the soul, trying to connect with someone, anyone, who might understand.

We’re in this together, to some degree whether we like it or not. When we lose someone like David, we feel that loss so much because he was, of all of us, one of the ones who supported others around him with both hands. I’ll miss him for that, and for many other things he was that have nothing to do with writing at all, and for being, like me, a whole lot of people trying so hard to be one person.”

I wish I could send this to him right now. I hope he knew I felt it all before. More than anything I wish I could grab a coffee with him in town and then walk down to the playground, asking, but not asking, the whole time, “Did I find it?”

Note: I emailed a few weeks ago about how users like me have asked Substack to immediately stop allowing its platform to be used by Nazis and other hate groups. Not only do they use this space to spread lies and violent rhetoric—Substack enables these users to earn money from that hate, financially aiding those causes, and profiting themselves.

Thus far, sadly, our requests have not been honored, and so I will be moving this newsletter to a new platform with better policies in the new year, if Substack sticks with in its position.

Free speech doesn’t mean all speech is permissible, anywhere or anytime. Private companies like Substack set their own user policies and can adhere to them, for the benefit of the other users of their ecosystem. Hopefully they’ll see the light here and change tacks, but if not, I’ll be in touch in January with a link to my newsletter’s new home. Thanks.

Suicide sucks

Sorry to hear of the loss of your friend. If possible enjoy your first(?) official hanukkah!