Writing With Both Sides of The Brain

Sketching my novel's characters helped me understand them... but why?

Two things before I start…

My novel Our Narrow Hiding Places is out today in paperback! Order it online or pick it up at your local bookstore!

This Fall I’m leading a The Great Gatsby at 100 reading group for The Center for Fiction! The class is online, so you can join us from anywhere. I’m looking forward to digging into the novel, and talking with you about its origins, revisions, and editors (including Zelda!)… and so much more. It’s 4 sessions between October and November, and you can sign up now!

A few years ago, working on my novel Our Narrow Hiding Places, I found myself stuck, badly, in a way I’d never quite experienced before. I tried and tried, spending months writing hundreds and then thousands of words that went right in the little digital recycling bin. I’d had blocks before, but they’d always resolved eventually with enough steady work, and patience. For some reason, I could find no way through. Words, scenes, and conversations all came to me, but everything still felt too distant.

Our Narrow Hiding Places, is about a young girl’s life in Holland during the end of WW2, and the stories were building on ones my Oma told me about her childhood. In this sense I was not lacking for material—I knew just what there was to say because she’d told me, in detail: about her struggles to survive starvation at the age of eight, and the way it felt to live alongside daily V-2 rocket blasts, and so on.

Dutifully, carefully, I described these things again and again, but to no avail. I had her interview transcripts in front of me, ample research from other books—and my head was spinning with ideas. I had a sense of the layout of her apartment building, and an old British war map of The Hague had given me a precise layout of the streets she was roaming through. I had books filled with period photographs of everything, including the exact street and building that my Oma had lived in then—in one of these I could even see the narrow windows of the attic where her father and the other men in her building had hidden from the Nazis during the Hunger Winter of 1944, rather than be forced off to work camps. It was all right there. So what was the problem?

I shared some pages with a friend, and it took them all of three minutes to put their finger on it.

“I can’t see it at all. I can’t tell what anybody looks like,” they told me.

That’s all it took for me to realize that I certainly didn’t know either. Many of the characters were based on relatives of mine—people I’d either never met, or only known in older age. Normally, writing about characters I’d invented, I had to begin by describing them, if only so I knew what they looked like, and they could begin doing things there, in my imagination. But I’d skipped this part somehow, lost in all my facts and dates and research.

Who was my grandmother, my Oma, at age eight? Did she look at all like my own daughter? My son? Who were her parents and neighbors? We had almost no photographs of them during the war years for the obvious reason that the family’s camera, along with most other personal items, had been taken by the Nazis occupying their city. Besides, everyone had been either starving or freezing to death—they weren’t documenting the experience for posterity.

Who were these people? How could I have written well over a hundred pages of a draft of my novel without having the slightest idea?

“Why don’t you draw them?” my friend suggested.

“Like write out little character sketches for everyone?”

“No,” they said. “Draw them.”

I did. And it worked. After just ten or fifteen minutes of sketching, I knew immediately who they were. When I came back to my novel draft, everything suddenly moved easily again. The characters before had been abstractions, all but puppets to deploy my research and to move the plot along. Within hours they were alive. I could hear their voices, see the ways they moved about, picture the expressions on their faces.

It worked. But why?

As a child, I drew all the time, long before I knew how to write. One of my earliest memories is of making pictures of monsters with my Opa, down in the cabin of a gently-rocking boat, during a family vacation when I was five years old. Someone had bought me a big purple book that showed, line-by-line, how to draw various magical creatures. Each was a kind of double; if you flipped the drawing upside down, the monster’s various folds and creases and horns and claws would invert, becoming new pieces of a different monster, hidden all along in the image—a bit like the classic optical illusion of a duck that is also, seen the other way, a rabbit.

From one angle my drawing would be grotesque and frightening. From the other it appeared cute and cuddly. I must have spent hours on that trip, drawing in the cabin of that rocking boat, watching my Opa’s hands skillfully creating these things that I, with shaky fingers, tried my best to mimic.

As I got older, my shaky fingers took a greater interest in making letters, words, and stories, but I always saw them quite vividly in my mind’s eye as well. While busting imaginary ghosts in my friend’s yard at night, I had no trouble convincing myself that, actually, they were totally real. I could convince myself they were there, moving, in the shadows around us.

The grade school tales I scrawled in my school notebooks always included little drawings of the characters: superheroes and dragons and, of course, more monsters.

But as I got older and illustrations fell away from the books I was reading, my artistic scribblings separated themselves from my literary ones. When I wrote stories then it seemed important that these be words-only, as that was what grown-up books were like.

Separately, then, I took art classes after school twice a week, in a little studio called The Leneve School of Art, located a town or two away, was a one-room operation run by a kind, gray-haired woman named Jean. I’d sit there on a wobbly stool for an hour, listening to an Enya cassette, Bob Ross posters on the walls. We’d paint or sketch on one of four long tables so thoroughly plastered in colorful dried daubs of paint, that you had to use a heavy board underneath your sketchpad to keep it from coming out bumpy.

Ms. Jean rarely made us work on anything specific. If you didn’t know what to make, she would tell us to dig around on her bookshelves and find something to copy—this was the best way to learn, she explained—by copying other pictures as best we could.

My go-to was a book of Robert Wyland murals of orcas and other sea creatures: stunning, smooth, dark ocean-dwellers that glided against backdrops of clear blues and greens. The challenge was to try and get the gooey acrylic paints she supplied to match the colors in the original pictures, and to try and make the lines with the same fluidity and proportion.

Art, at the Leneve School, was about accuracy—a good picture, in Ms. Jean’s eyes, was one that looked as much as possible like the original. Some of the other kids found this frustrating. They wanted to just paint things from their own imaginations. But I loved training as a copyist, becoming a kind of junior art forger.

I was always slow. It took me months to finish a single piece—but I was patient, deliberate, always so fully absorbed that I could never believe the hour was over when the time came to go home.

Sometimes I’d bring in books from home and copy their jackets on my own canvases. Over the course of a year, I painstakingly copied the covers of the four Wrinkle in Time books by Madeliene L’Engle, which I had become obsessed with. In high school I continued to take art electives every year in high school, and briefly considered taking an AP Art course, but I had never developed a particularly strong sense of composition—for all my years of copying, I’d never really figured out how to make anything original.

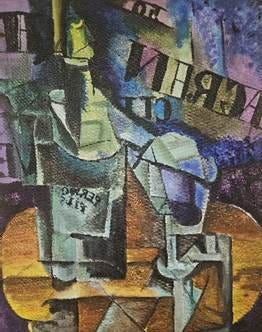

Fortunately, I found this much easier to do in words, and so I shifted my energies into writing stories, and I was both quicker at that, and more confident in my own vision. Still, I missed the brush and the canvas. During college, between creative writing workshops, I painted the sets for our theater group. For a ritzy living room in Rumors, we made frames out of plywood and stretched canvas over it, and the techies mocked up a Mondrian and then a Rothko. After my finals were over, I took some of the leftover materials and made myself a huge 5’ x 3’ canvas and set to work:

Like everything else I’ve painted, this is a copy—of what I can no longer remember. My memory is that I found the original picture in an art book about Futurism and hadn’t been able to get it out of my head. The colors were bold, ideal for the acrylics (all I’d learned to use at the Leneve School.) Plus the cubist shapes were easy to sketch out on a penciled grid—another copyist technique I’d picked up from Ms. Jean.

The painting succeeded in clearing my head of a year’s worth of stress and strife and priming me for new creative endeavors in the months ahead.

This became a kind of ritual. Each summer afterwards, I’d set aside a few weeks to make another. I forged several Picassos and then a Juan Gris. They weren’t exactly going to pass at the MoMA, but they made me happy and engaged parts of my brain that hadn’t been turned on in a while.

I began to run out of walls in my apartment to hang them on, so I started to give them as gifts for friends and family, as decorations for friends’ offices. I tried my hand at new styles: Kandinsky, Bacon, Goncharova, but always bright, always playing with forms and shapes in some way.

They were joyful to make and joys to give, and as someone who often struggles to take a break from laboring on stories and novels, they gave me a welcome shift in perspective. I didn’t think of these art projects as being connected, anymore, to my writing—but in a sense they very much were the other side of a creative cycle, a different way of expressing something, even a copy of something, as my brain reset itself again.

How could I have forgotten?

By the time I was working on my World War II novel, it had been almost a decade since I’d painted anything. I thought about it sometimes—I kept seeing paintings that I imagined would be fun to copy—but I was a novelist now, I told myself—and even when I was not focused on a book, there were always more stories and essays and things to write than I had time to write. Add to that two children and a full-time teaching job and the idea of setting aside even a week or two over the summer break to paint something felt like an unaffordable luxury.

Watching my children play, I had become aware already of a kind of loss in my own imaginary powers—something I’d accepted as the inevitable process of aging, my brain having now developed into something else from what it had been then. When I wrote now I felt a kind of music in the language, and could hear the dialogue going back and forth, but I didn’t see anything like I used to. Not like my children could. Suddenly I began to wonder if it wasn’t just some natural shift in the neurons, but just a skill I’d accidentally allowed to atrophy. At their age, storytelling and imagery were all one thing to me. As I got older they’d come apart, but through those paintings maybe I’d managed to keep the visual parts of my brain strong. Perhaps all that had happened was that I’d neglected to work those lobes out—the neuroscientific version of skipping leg day.

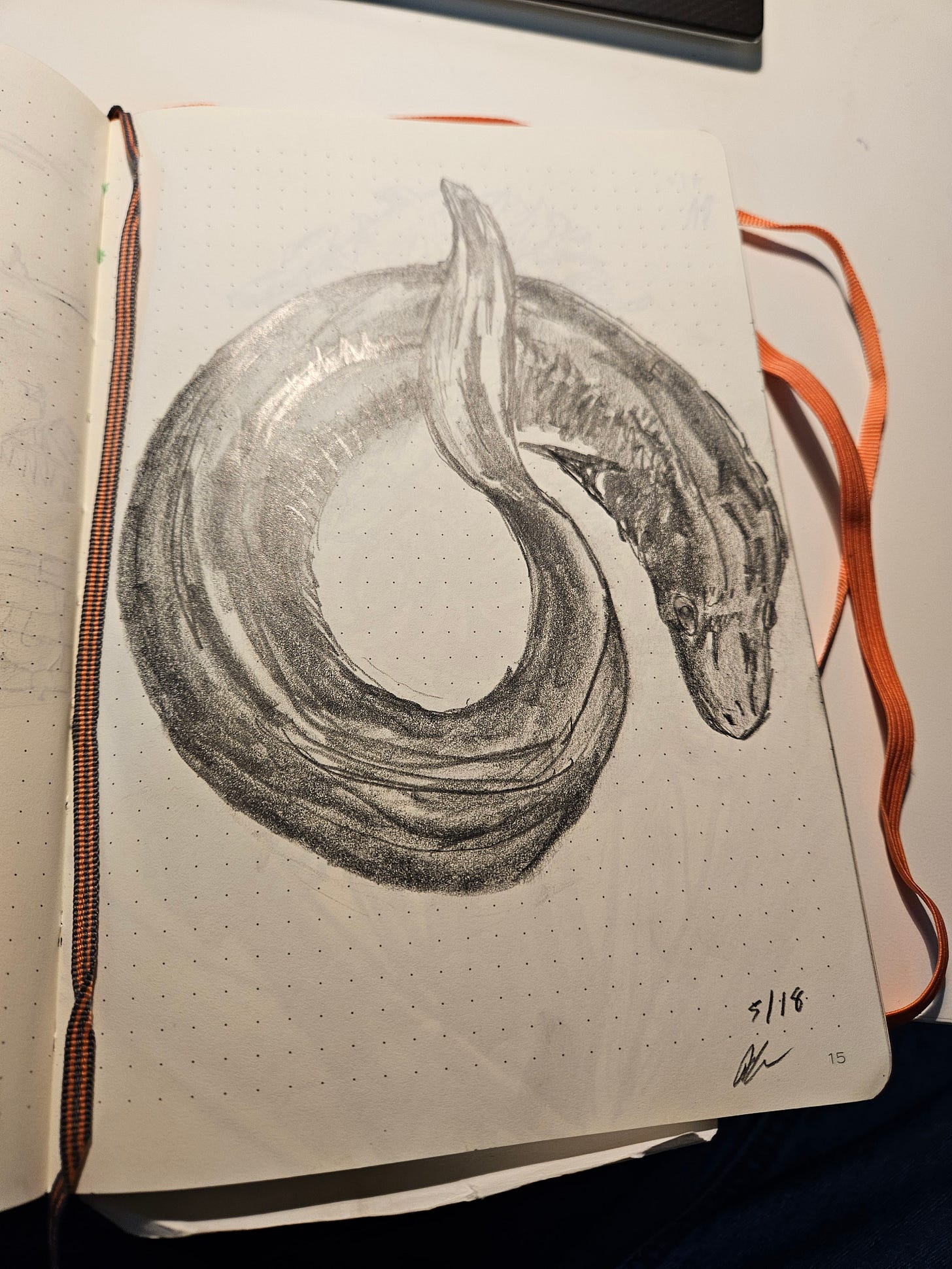

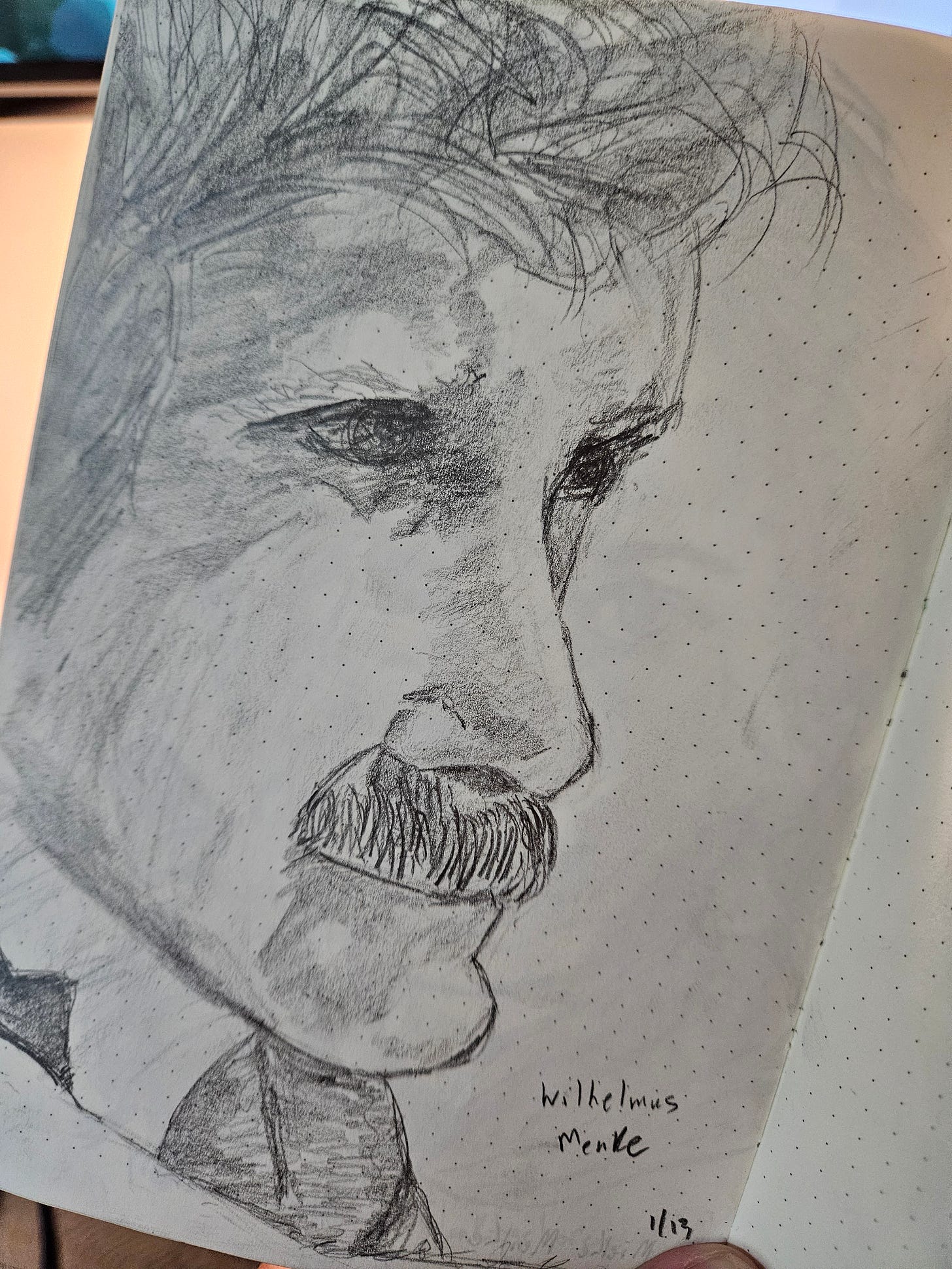

Soon I began to start each daily writing session with a little fifteen-minute drawing session. Even when, some days I barely had an hour free for writing, I decided it was essential to use a quarter of that time for sketching. I’d pick a character, or an object from the scene I intended to work on and rough them out in a notebook.

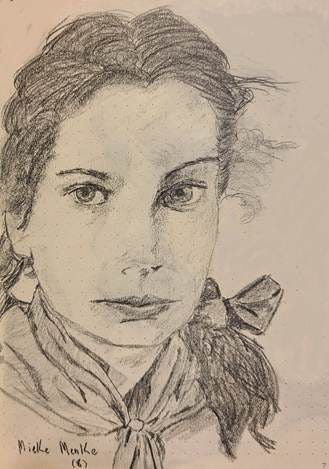

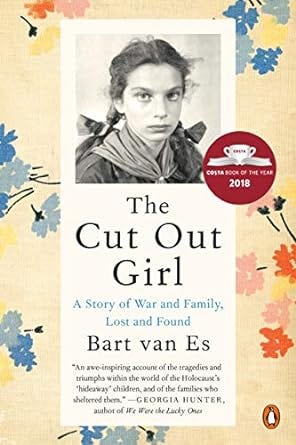

To draw my protagonist, Mieke, it made sense to look at some pictures of my real-life Oma. Only I still had no photos of her from that period. I decided to work off of a photograph on the cover of one of the research books I’d read, The Cut-Out Girl by Bart van Es, also about a Dutch girl around the same age during the same time period.

She wasn’t my Oma, but she could be my Mieke in the novel.

Gradually I began to see Mieke for the first time: the defiant mischief in her eyes, the lips clamped shut as if holding back some secret, the hair a little wild, coming out of the braids someone had put in. These tiny, external details reflected the person I knew she was on the inside. In real life, we form quick unconscious assumptions based on a person’s micro-expressions, in order to guess at how they’re feeling on the inside. Angry? Sad? Worried? Elated? With my pencil in my hand, drawing, I felt like this same automatic instinct was turned on in the same way as if I was meeting a stranger in real life. Something in my unconscious mind was turning the flat image into a full, three-dimensional person, with hopes, dreams, fears, secrets. All in fifteen minutes of sketching.

By the time I finished, I felt I knew Mieke completely. And when I sat down to write about her then, the words poured out. She was all there in my head at last.

In doing verbal work, we activate the frontal, left hemisphere parts of the brain uses when speaking or articulating ideas, utilizing something called “Broca’s area.” But when we visualize things, and when we compare again and again the slight similarities and differences between an image and its copy-in-progress, we are working in the far back end of the brain, almost as far away as you can get from the verbal parts, much closer to the brainstem, in the visual cortex.

A classic guide to creativity, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, written by Betty Edwards in 1989, delves into the ways in which an artist can unlock their full potential through a series of simple drawing exercises—even if they have no real training or experience as a visual artist. Describing drawing as a “global” skill, Edwards explains that it is similar to reading and writing in that the larger ability to draw is made up of a number of basic skills which must be learned separately and then eventually brought together through repeated practice. Similar to how we can eventually walk, drive, or play a musical instrument, without needing to constantly consciously think about balance, traffic merging, or fingering—when we draw and when we write, we are aiming to achieve a kind of natural flow that does not need to be constantly checked-on, unless something is “off” for some reason. Edwards further explores the idea, commonly held at the time, that a person’s visual and perception skills needed for drawing are located in the right-hemisphere of the brain, while their verbal and language skills are over in the left. In an updated edition of Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, Edwards concedes that these concepts have become outdated in light of modern neuroscientific discoveries—there is considerably more overlapping work occurring in the brain when it comes to visual, or verbal activity, and these are not so neatly organized into the left and right hemispheres as once believed. But, Edwards explains, we can think of them rather as different “modes” of brain function, which she calls L-Mode and R-Mode, which still often operate independently of one another.

In layman’s terms, when we are writing a story using words, and constructing sentences according to logic and grammar rules, we are using our brain’s “L Mode.” But when we begin to draw a picture, something that the L Mode cannot oversee and therefore “turns down,” our “R Mode” will take over and we will regain access to those “subdominant” visualization functions needed to “see” something more fully in our imaginations, the way an artist must.

For ages I dismissed my visually artistic side, despite the joy it brought me, because I could only really copy other things. I doubt I’ll ever evolve beyond careful mimicry—but then again I suppose I have little desire to try it.

Now I understand how important it is to the larger creative life I’m attempting to live, and that there’s nothing about getting older that prohibits my imagination from seeing things that aren’t really there. It just takes a little exercise now, which it didn’t back then—so it goes with every other part of me as well in middle age. I’m grateful to see now that there’s much to be regained with just a little effort.

When I draw things now, when I am copying, I’m there in the cabin of that boat again, making upside-down monsters with my Opa, building those little localized skills up, one by one.

When I sit down and put pencil to paper, for only a little while, and I begin to see the things that happened in his life that he never got to tell me, half a world away and forty years before I was born. And then, in words, I can make them real again.

Love this! We read that book in art class and I think of it a lot!