What’s in an Epigraph?

How my quest for 11 lines of a poem led me on a strange odyssey to a "religion of non-conformist thinkers" in Holland.

You know those little quotations authors put in the fronts of their books? They’re called “epigraphs” and their use goes back to at least the 15th century. Assuming the reader doesn’t flip right past them, they’re meant to be the first thing encountered after the title and before the novel actually begins.

Think of them like an amuse-bouche at a fancy restaurant, passed out as you settle in for a meal, preparing you for all that’s still to come.

An epigraph might set up some themes, establish a tone, or even pose a question? It also connects the work you’re about to begin to some other works preceding it, providing some glimpse into the author’s intentions or inspirations. Used properly, an epigraph sets up some kind of key expectation or expectations.

A book that starts with some pop song lyrics is going one way, and a book starting with a Bible verse, another. Of course it’s common to mix and match—a contemporary novel might toss up a Shakespearean couplet just above a Dua Lipa verse, perhaps indicating that the book aims to be both for the present moment and for all time… also serious and fun at the same time.

With my novel, Our Narrow Hiding Places, I stumbled upon an epigraph I wanted to use fairly early in the writing process, but I never imagined how complicated it would soon make my life.

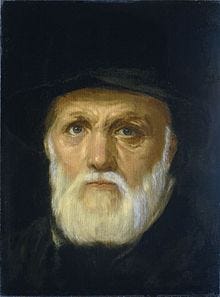

I’d chosen a quote from a poem called “Honestum petimus usque” by Dutch writer Albert Verwey that seemed to resonate with the experiences of my characters. He described a world at war, coming apart at the seams, neighbors becoming alienated from one another, as people turned ruthless, if not mad. And yet the pompous Latin title bore some kind of nobility, coming to something like, “Always seeking honor.”

Do you not suffer? The world has declined.

It no longer rolls melodiously from God’s hand.

Beautiful peoples turned into hordes,

The human mind raised into madness.

The firmly founded bond of all together

Bursts at the seams and there is no law.

There is no more shame and no decency.

No fixed road where everyone puts their feet.

- Albert Verwey, “Honestum Petimus Usque”

This is the quotation as it appears in Our Narrow Hiding Places today, but getting here was quite a long and winding road, one which I frequently thought would turn into a dead-end.

I’d discovered the poem while googling Albert Verwey—he was a Dutch poet from the period just before the war began, and I’d enjoyed another poem of his called “How I Loathe These Days Full of Sun” (how could you not, with that title?) but as much as I loved the tone of it, it simply didn’t fit the vibes for this novel.

Hunting around for more poems of Verwey’s I ended up on the website Lieder.net, a free archive of choral works and here found Honestum Petimus Usque. I’d taken enough Latin in middle school to rough out the title and it seemed like it could be on point for my book. But the poem itself was not in Latin, but of course in Dutch.

In a hurry to see if this was worth pursuing, I dropped it into Google Translate and got a rough sense of the meaning (which I then tidied up).

Aren't you suffering then? The world has degenerated.

It no longer rolls melodically from God's hand.

Clean populations became hordes.

Human reason rose to madness.

The well-founded connection of all together

Splashed at the seams and there is no law.

There is no more shame and no more becoming,

No fixed street where everyone sets their feet.It felt right, though there were some issues… “splashed at the seams” didn’t feel right somehow, and I didn’t know what “no more becoming” really meant… but it was close enough for the time being.

I intended to get someone to do a proper translation at some point, of course, but this soon fell onto the back burner and I forgot all about it. (This is the nature of the epigraph for readers too in many ways.)

Only when the novel was, many months later, heading into a late round of edits, my editor flagged the quotation and suggested I check on the translation and the rights.

I reached out to another writer, Cam Terwilliger who I knew had also been researching a lot of Dutch history for his work. Cam soon put me in touch with a man named Klaas van der Hoek, the Curator of Manuscripts and Modern Literature at the Allard Pierson Museum of Antiquities, part of the University of Amsterdam.

Though my poem was fairly obscure, Dr. Van der Hoek knew the piece right away. He explained that it was actually a libretto for a piece of choral music, composed by Henk Badings for students in something called the Amsterdam Student Corps in 1936, just a year before Verwey’s death. He said he’d be very happy to translate the poem for me… just one small problem, which was that the version I’d read on Lieder.net was inaccurate.

He compared their version to an original that he had accessible, and a few of the key words had been miscopied at some point. This meant I had gotten several words wrong even before it went into the AI meatgrinder of Google Translate.

Along with other minor issues, this accounted for “splashed at the seams” and “no more becoming”.

Luckily, Dr. Van der Hoek was able to soon set things straight, and he provided the translation we used (and which I pasted above).

Happy to have figured this all out, I assumed the matter was settled at last.

But a few weeks later, my editor emailed me again. The publisher’s legal team had concerns about the copyright. Even though Verwey had died in 1937, and even though the “poem” was totally out of print in English (and in Dutch, according to Van der Hoek)… they had concluded that we could not quote from it without permission from the Verwey estate.

When you are considering a quotation for something like this, typically you want to determine if your sample is short enough to qualify as what we call “Fair Use”. A few sentences from a big novel (or even a short story) is fairly easy to justify, since it is a tiny portion of the whole. But with poems, and songs, it gets complicated because the whole piece is fairly short.

The entire poem was 88 lines long; I wanted to use 8 of those lines, or 11% of the total poem, which put us outside of the usual Fair Use exemptions. Nobody seemed to know how the international nature of the laws would apply—did we have to follow Dutch law? American law? More troubling, how was I even supposed to find out who could grant this permission? It wasn’t like Albert Verwey had a literary agent I could call… he’d been dead for almost ninety years.

At this point I more or less resigned myself to the reality that the epigraph would need to be cut. I would have to go back and find something else, or simply go without—I had a quotation from the diary of a Dutch woman named Etty Hillesum who had been killed at Auschwitz:

The world must surely have collapsed at least once in the lifetime of every individual, yet strangely enough it still exists.

But I didn’t like how it hung there all along. It was more colloquial and ironic. It didn’t work as well without the sincere poem above it.

I did look for a few days, but nothing I found came close to working as well as the Verwey poem.

Desperate, I went back to Dr. Van der Hoek and asked if he might happen to know who represented Verwey’s work now.

Thankfully, he knew just who to ask.

He told me to email Dr. Gerlof Verwey, grandson of Albert, the founder and chairman of something called “the Coornhert Stichting.” This turned out to be an institution dedicated to the work of a 16th century Dutch “idiosyncratic thinker and artist” named Dirck Volckertsz Coornhert. Googling the organization, I saw that it came up as a church, and indeed it turns out to be dedicated to what they call the “religion of non-conformists” who are inspired by the teachings of Coornhert.

By now I was beginning to worry I had fallen sideways into some kind of bizarre academic satire—something, I suppose, I’d long dreamed of doing—but I decided to email the acting secretary of the non-conformists and request permission for the use of those eight lines from Albert Verwey’s grandson.

I waited almost a week and then, just as I was about to give up hope, I received an email back:

I gladly give you permission to quote those lines as epigraph for your novel.

With my best wishes for the success of your novel to be,

Dr. Gerlof Verwey.

We had it!

From there it was just a matter of having him sign a permission form and email it back to us, and the whole matter, finally, was done. The legal department would be satisfied, and the epigraph would stay in.

When I look back on it now, and the hours it took, over many weeks, to figure it all out, I’m a little amazed that we got there eventually. Was it really so important? To squeeze those eight little lines in there, that amuse bouche that no one would really miss, and that maybe most readers would simply skip over anyway?

Maybe not, but then again, writing a novel is all about, well, nonconformity, thank you Mr. Coornhert. It’s about trying what others haven’t, or wouldn’t, allow themselves to try. It’s about pursuing the thing that has captured your attention, regardless of how time-consuming or silly it all ends up becoming.

Almost everything about writing a novel is like this. Every choice you make in the book, from the title to the last line of the acknowledgments page, has to be weighed and considered. Ultimately it all has to be fought for, in some sense or another, and that fight is what gives it all more meaning. A novel represents a mass of deliberations that has become, in the end, a printed and unalterable text that hopes to impart something: knowledge, joy, wisdom, heartbreak, beauty… it takes a long time because it hopes to remain with readers for a long time, and just as every tiny brushstroke of a great painting matters, so does every sentence in a novel, including even the humble, bold, profound, silly little epigraphs.

I know that, after this, I’ll never take one for granted again.