Sketchy Characters (#3)

Today’s Writing Music: “Everybody Breaks” by Ivan & Alyosha

Today’s Reading: Men Without Women by Haruki Murakami (which has the short story that the film Drive My Car is based on!)

Here at last, the final of these three posts on character. If you’ve been following the previous two, I’ve gone through the process of developing characters for fiction, layer by layer. First, we considered physical description and a character’s perceptions by others. Next, we looked at how a character’s society shapes them, and how useful ironies exist in the gap between that outermost layer and the next: a character's internal sense of themselves. Now, we’ll get into the third (and final?) layer of a character—the thing that hopefully completes the job of fully bringing them to life.

In the last post, I talked about how James Wood, in his book How Fiction Works describes a Dostoevskian character (which I think we’re to take as meaning a “modern” character) as having three psychological layers. First, their stated motive, which might be how the character describes their own purpose in life/the story. Second, their unconscious motive, which would be, on some deeper layer to which the character may not have full access, but which we can see as close readers—the actual reasons whey they’re doing what they’re doing.

Raskolnikov, in Wood’s example, murders a woman, stating all the while to us that he is doing it as a kind of philosophical experiment. By killing an ordinary person, without feeling remorse, he'll prove that he is superior to the moral structures of his society. He believes himself to be what Nietzsche will later call the “Übermensch” or superman.

But later, the guilt over his crime finally does drive him to confesses to a prostitute named Sonia. He then runs through a series of attempts at getting to his real reasons for committing the murder.

First he says that he killed the woman because he was poor and needed money. Then he adds that he also found her to be a blight on society (she was a pawn broker) and did so to benefit everyone else.

But these are still stated reasons. They are logical justifications he’s come up with afterwards. To get to the “real” reason, we know he'll need to get down into layer #2: the psychological.

Raskolnikov eventually suggests that his poverty has made him mentally unstable, saying, “low ceilings and small poky little rooms warp mind and soul.”

He sees his motivation was somehow compulsive—but emanating from what? The reader can guess at what's truly warped… is he a misogynist, or does he feel sexually inadequate? Was he really trying to kill his mother in some pre-Freudian outburst? You can write paper after paper looking into any of these interpretations, and many have. Examine Raskolnikov through any established critical lens and you'll find much to say.

And many writers might stop here too. They'll have created a pretty realistic character, with two interesting layers that drive a compelling plot. In the end we have lots to consider about human nature and morality and all that jazz.

But-- it isn't quite enough, is it? Something else has to be going on, we think. Why did *this* particular Russian man do *this* particular thing? We need a third layer still. Raskolnikov needs some secret that lies even deeper down.

One move here would be to reveal some traumatic event in his past that adds context to, or even explains, his actions. Give Raskolnikov some hidden wound that lies at the heart of him, either repressed or hidden away. Freud argued that shame is one of the most powerful forces in the human mind, causing us to act in incredibly strange ways.

This would be a natural direction to go, and many writers, including myself, have found it an excellent third layer.

On the other hand, if it is too obvious, isn’t that a problem?

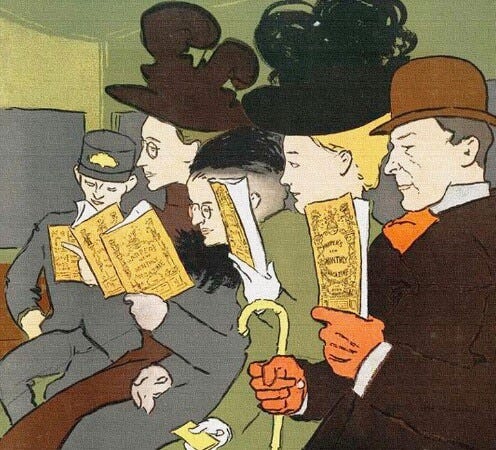

Parul Sehgal, in a recent issue of The New Yorker, breaks down the “Trauma Plot” (and makes a strong case against it). She talks about an essay by Virginia Woolf called “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown” where Woolf describes seeing a woman on a train who is weeping.

Woolf, almost helplessly, began to spin a story herself—the cottage that the old lady kept, decorated with sea urchins, her way of picking her meals off a saucer—alighting on details of odd, dark density to convey something of this woman’s essence.

In making this real woman into a full fictional character, Woolf is tugged in a familiar direction—towards her darkness & trauma. We know it well. Something terrible has happened to this woman (hence the weeping, but surely also something else, even farther back/ deeper down) and, over many chapters of lyrical and meticulously rendered detail, we’ll come to discover finally what it was that has wrecked her so badly. Trauma, abuse, betrayal—she’s hiding some psychic wound, deep inside, that has never been healed, only covered over. Whatever it ends up being, it’ll explain (and perhaps even excuse?) her seemingly strange choices and actions along the way.

Perhaps she will act “badly”—maybe she's cruel or selfish or manipulative… this is fun because then we get to write about our character doing all the fun, transgressive, antisocial, edgy stuff we want, and then make the audience feel like it was all the fault of their trauma later on.

Or maybe our character is driven towards some megalomaniacal goal, like killing the White Whale, or making a fortune to impress Daisy Buchanan, no matter what laws are broken along the way, or lives ruined. That works. It’s their trauma you see, that made them do it. Their unfairly-taken limb. The romantic rejection they faced because they weren’t rich.

Obviously this works, and has worked, for a long long time. I’ve been trying to read a short story every day this year, as part of my "Five Point Plan” for 2022, and I’ve kept careful track so far. Of the 48 stories I’ve read as of this writing, well over 30 hinge on some kind of trauma: dead children are popular, and dead wives. War, and exile from one’s homeland. There have been stories about racist and sexist traumas. Stories about abuse. Loved ones lost to suicide. Struggles with mental illness, and so on. And I don’t mean to malign any of these traumas—they’re all quite real. I’ve experienced a few of them personally, and I’ve used a lot of these in my own stories and novels also. I’m a big believer in the idea that writing through trauma can be not only healing to ourselves, but healing to others. It’s a fantastic and powerful reason to write fiction.

What Sehgal is asking in her article, however, is just that we don't jump right to Trauma every time. Whenever something becomes a convention in fiction, fiction needs to recognize it and challenge it, in order for novels to stay “novel” and characters to feel truly alive. When something like the Trauma Plot begins to feel predictable, we end up drawn us out of the experience and we feel unsurprised, and even uninspired in the end.

So what are some other options? One might be to satirize the idea of a trauma plot, which I see a lot. “Girl with Curious Hair” by David Foster Wallace is a good example of this—our character is “Sick Puppy” a sadistic young man at a concert with several punk rocker friends, as he contemplates violently killing a random young woman in the crowd (shades of Raskolnikov). As the story goes on, we find out that SP is sexually sadistic, clearly psychotic. We are eventually told that he and his sister were horribly abused as a child by their father. Some probably read the story as a gross, misogynistic, violent fantasy. But Wallace wants us to be very disturbed by SP, and the extreme/over-the-top nature of the setup has always felt more like a parody of the Trauma Plot. The story asks us to think about how much trauma can really explain. We cannot sympathize or even really better understand someone like Sick Puppy, just because we’ve been told they’ve been victimized themselves. (In fact, according to editor Gerald Howard in an article at Vogue, the story is “an obvious and expert parody of Bret Ellis’ affectless tone and subject matter”—a theory he floated to Wallace, who denied having ever read Ellis’s work.)

So that's one option. This week, I read a story “An Independent Organ” by Haruki Murakami in the collection Men Without Women. In the story, the narrator describes a friend, Tokai, who unknowingly led a life that was “surprisingly artificial” due to his lack of “intellectual acuity.” Tokai is “perfectly guileless” and believes himself to be living an honest life “devoid of ulterior motives or artifice.” (In other words, he's someone who thinks his own stated motives are the whole story, and has no deeper layer.)

I was struck by the idea of a story about a character wholly on surface, because the normal rules of fiction would say that this won’t work. The story acknowledges as much: “As my reader is aware,” the narrator says, “affable people like this are most often shallow, mediocre, and boring.”

Murakami’s narrator speculates that many of these people in life never see clearly how wrong they are, and are blessedly happy as a result. On the other hand, those like Tokai, who are made to see the inner workings, are liable to crumble as a result.

So there is some drama in the idea that the usual path towards a character’s self-discovery, in this case, will lead to disaster. What would do this?

In Tokai’s case, it is love—he has long had shallow, physical relationships with women (often married) but never felt anything deeper for these women. But by chance he meets someone who breaks through, and he falls in love. It’s the textbook setup for a romantic comedy, of course, and if the Trauma Plot held, we’d find out, just at the climax, that Tokai was hurt somehow as a child—divorced parents or something even worse—and that’s led him to be a hollow loveless person. (But no more!)

Only that’s not what happens. Falling in love with this woman instead makes Tokai question his programming. “Who am I?” he asks the narrator. He’s a plastic surgeon, “conscientious” about his work, a professional, living in a “happy environment”— but, he says, if you take away all those things, who would he be?

Because Tokai has no traumatic backstory, he struggles to imagine his true self. When he reads a book about the Holocaust, where Jews in the Nazi camps are stripped of their jobs and families and happiness and hope, Tokai wonders who someone is, without all those things? When that’s all stripped away, what’s left?

Sadly, in Tokai’s case, this question leads him to begin traumatizing himself. He eventually starves himself to death in a Kafkaesque twist (Murakami’s a big Kafka fan, and this story brings to mind “The Hunger Artist” as well as “In the Penal Colony”).

In any case, this seems to me like another take on the Trauma Plot. Wallace parodies it, and Murakami, in a way, tries to do a postmodern dance with it. Both are excellent stories, but, I think, ultimately restate the problem, rather than offering a solution. How else can we define characters, and give them layers and depth, without some concealed trauma?

Let’s return to Raskolnikov. We were stuck at Layer #2, if you recall. He’s offering shifting and conflicting reasons for why he killed the woman pawnbroker. We can psychoanalyze him and dream up our own (totally satisfying) reasons too.

But, Wood argues, there’s something we’d miss, if we left it at that.

The last explanation that Raskolnikov offers is that he killed the woman due to some inner loathing of himself, and/or some demonic influence: “Was it the old hag I killed? No, I killed myself, and not the old hag. I did away with myself at one blow and for good. It was the devil who killed the old hag, not I.”

There’s another layer here. Why does he want to be able to behave free of societal constraint? Why does he liken himself to God? And then, why does he say it’s all the devil to blame? Something theological plays a role here.

“The third and bottom layer of motive is beyond explanation,” Wood writes, “and can only be understood religiously. These characters act like this because they want to be known; even if they are unaware of it, they want to reveal their baseness; they want to confess.”

Wood makes a good point here. Why does Raskolnikov even confess this murder to Sonia? Because he feels guilty, because he wants forgiveness. Because he wants someone to know. (Sonia, or God, via Sonia?).

My students sometimes get uncomfortable at this point, because I’m sure it sounds like I’m about to start trying to convert everyone or something. We’re usually pretty well-trained in the modern literary world, to write beyond religious dogma. Literature isn’t supposed to be religious, and some argue it shouldn’t even express any kind of morality (this is how I was taught, though not how I write now).

What does God have to do with creating characters, especially if we the writers don’t even believe in God, or if our characters don’t?

These are all great questions, many of which I have only my own answers for. But over time I think I’ve come to some understanding of what that third layer is, and why Wood thinks it is “beyond explanation”—moreover, I think I’ve even come up with some way of helping to guide myself (and others) to finding it.

For a fuller explanation of this, you can read this essay I wrote for The Center for Fiction many years ago, about a short story by Virginia Woolf called “An Unwritten Novel” that helped me to unlock this—but I’ll do a quick version of it for us here.

This Woolf story has a very similar premise to the one Sehgal talks about in her essay. The narrator, a writer, is on a train and becomes interested in a woman sitting across from her. She's not weeping, but she's clearly irritated by something. As the ride goes on, the narrator comes up with a name for the woman, Minnie Marsh, and a whole life, based on just a few little clues she’s noticed about the real woman.

These clues are: 1) that the woman says something bitterly about her sister-in-law, 2) that the woman scratches at an abrasion on the train window, and 3) that she nervously plucks at the skin on the back of her neck.

Woolf’s narrator reads these all as evidence that the woman feels guilty about some past sin—the writer describes a younger, naïve Minnie being distracted on her way home by some fancy ribbon in a store window. She loses track of time and as a result… something bad happens. Funnily enough, Woolf seems to almost joke that the specific trauma here isn’t important, just that one occurs (and she’s right).

Neighbors—the doctor—baby brother—the kettle—scalded—hospital—dead—or only the shock of it, the blame? Ah, but the detail matters nothing! It’s what she carries with her; the spot, the crime, the thing to expiate, always there between her shoulders. “Yes,” she seems to nod to me, “it’s the thing I did.”

As long as something terrible has happened to Minnie, then she’s interesting. Because she’s got something to grapple with, there between Layers 1 & 2, she’s good to go. Woolf is ready to run with a Trauma Plot.

But what about Layer 3? Well, Woolf takes Minnie in a fascinating direction here.

Describing the real woman gazing out the window, Woolf imagines that she’s looking for “her God” (in a cow field). Then she asks a simple, but revealing question:

“But who is the God of Minnie Marsh?”

She’s not trying to suss out this woman’s religious affiliation, of course, but rather to figure out who her God is. What does Minnie Marsh see when she thinks of God? What does she imagine?

More like President Kruger than Prince Albert—that’s the best I can do for him; and I see him on a chair, in a black frock-coat, not so very high up either; I can manage a cloud or two for him to sit on; and then his hand trailing in the cloud holds a rod, a truncheon is it?—black, thick, horned—a brutal old bully, Minnie’s God!

What’s the point of this? Well, it establishes Minnie’s idea of a moral order. A conception of her universe. Minnie believes she’s living in a world where God is a “brutal old bully” and so that’s going to move her differently as a character, than, say, a Minnie who believes that God is… whoever: Gaia, the Earth Mother, who wants us to live in harmony with nature; or Jesus Christ, who just wants her to love her fellow man; or maybe Minnie’s God is actually a bunch of gods: a pantheon of Hindu deities or something like that. To Wood’s point, her desire to be known by some higher power or higher order, might well explain her behavior even more than understanding, let’s say, that she’s from Cornwall, or Poughkeepsie (as Flannery O’Connor told us last time.)

OK, you’re saying, but what if my character doesn’t believe in God? What if I don’t either?

That’s a fair question. Most of my own characters don’t, and I’m not always sure if I do either. But again, this isn’t about pinning down someone’s specific religion, so much as explaining who or what they see themselves as answering to, in a larger sense.

Here’s my work-around for all my fellow agnostics and atheists. There’s a bit in the Joseph Heller novel, Catch-22, when his main character, Yossarian argues with Lt. Scheisskopf’s wife (who he’s sleeping with). “‘I thought you didn’t believe in God,’” he cries. She doesn’t, she replies, but “‘the God I don’t believe in is a good God, a just God, a merciful God. He’s not the mean and stupid God you make Him out to be.’” Ultimately Yossarian offers a compromise. “‘You don’t believe in the God you want to, and I won’t believe in the God I want to. Is that a deal?’”

Instead of asking yourself “Who is the God of (insert character name here)?” you might ask, “Who is *not* their God?” When they stare out a window at a cow field and think about what who they don’t believe in, what are they imagining?

It may just work.

There may be many other options for a third layer—I wonder often about how science might fill this space. Can joy hide down there in the third layer, rather than trauma? Could a character’s genetics sit here? Is intergenerational trauma an interesting enough variation on the Trauma Plot, or more of the same?

What other kinds of secrets might lie at the core of people, and therefore, at the core of our characters?

It’s one of the most interesting questions there is to ask while writing, and reading. How we choose to fill in that third layer says a lot about our own points-of-view, our own case-to-make about life and its meaning when lived by a human being.

Whatever we choose to put there, it is ultimately some deeper attention to that third layer that takes a character from being a bunch of words, or an intersection of types, and turns them into a Someone we know and care about.

Writing Towards the Fun #23:

Try out the Minnie Marsh approach… take a character that you’ve already developed through the first layer or two, and ask yourself this question:

“Who is (not) the God of ____________________?”

Remember, we’re not just talking about what organized faith they do or don’t subscribe to, but we’re looking for some kind of specific vision of God/gods/higher power/universal order here… like the “President Kruger” model that Woolf uses. What does He/She/It/They look like, if they were also a person?

Take a minute to write a paragraph describing this vision from the character’s point of view. Do you feel like you know them better now?

Have fun!