Today’s Writing Music: “All My Favorite Songs” by Weezer (feat. AJR)

Today’s Reading: The Morning Star by Karl Ove Knausgård

“There is nothing harder than the creation of a fictional character,” observes James Wood in the beginning of the chapter on Character in his book How Fiction Works, an assessment that I would agree with wholeheartedly—one reason that this post is going to be the first in a series of three, each going a successive layer deeper into the creation of great characters.

There are many things that matter in a successful story: a compelling plot, a well-built world, a keen attention to the sentences… but none of that really matters if the characters in the story are leaden, boring, just plain dead on the page.

I have enjoyed plenty of entirely plotless stories, because they explored interesting characters. I can’t say the same in reverse: a well-plotted story without good characters sends me right to sleep.

So, it’s important, and, as Wood argues—hard.

Why is it so hard? Because it is nothing short of creating life. (Not to be overly dramatic about it.) A great literary character is alive, in the mind of the reader. It’s only because they exist in our imaginations that we care about them.

And we can care a lot. (I still can’t talk about Bridge to Terabithia without tearing up, and it’s been like 30 years since I read it). We worry if a character we love is in trouble. We cry when they die. We cheer when they find love and happiness. They’ve become much, much more to a reader than just a particular arrangement of words.

And again, when that doesn’t happen… there’s not much point in the rest, is there?

So how is it done? Would it be easier to discuss how it is not done?

Wood’s chapter in How Fiction Works outlines several major pitfalls—static descriptions where an author seems to be describing a photograph, a lack of detail, an overload of detail, and so on. He also notes there is a ton of bad advice out there for writers: that we should get to “know” them, that they can’t ever be stereotypes, that they need interiority, that they should “grow and develop”, and that they should be “nice.” A reader must “approve” of them in some way, or be made aware that the author definitely does not. On and on.

“A great deal of nonsense is written every day about characters in fiction,” Wood concludes.

Maybe the best thing to do, to start, then, is to push away everything we’ve been told before. Take it back to the basics.

Begin at the surface—what I think of as the first layer. This is the layer at which we encounter almost everyone in life, and actually rarely get beyond.

Strangers. You encounter strangers almost every day of your life. Guy on sidewalk. Bus driver. Barista. Lady in parking lot. Child in school bus window going by. We take in dozens of these faces every day, and then almost immediately forget them.

Even someone we’ve bumped into, had a brief exchange of words with—we may have trouble recalling in any sort of detail, five minutes later. Most people make no impression on us whatsoever—my understanding is that this is likely an evolutionary imperative. How could we function if our brains never edited out all of these extraneous human beings from our daily mental recordings? We’re built to forget—if we even notice in the first place.

So, we have to train ourselves to be better at noticing in the first place. Adherents of meditation will tell you that this is one part of basic mindfulness, something we can exercise through practice.

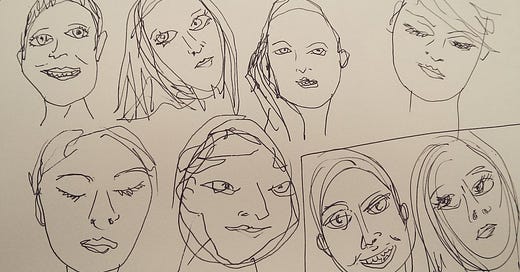

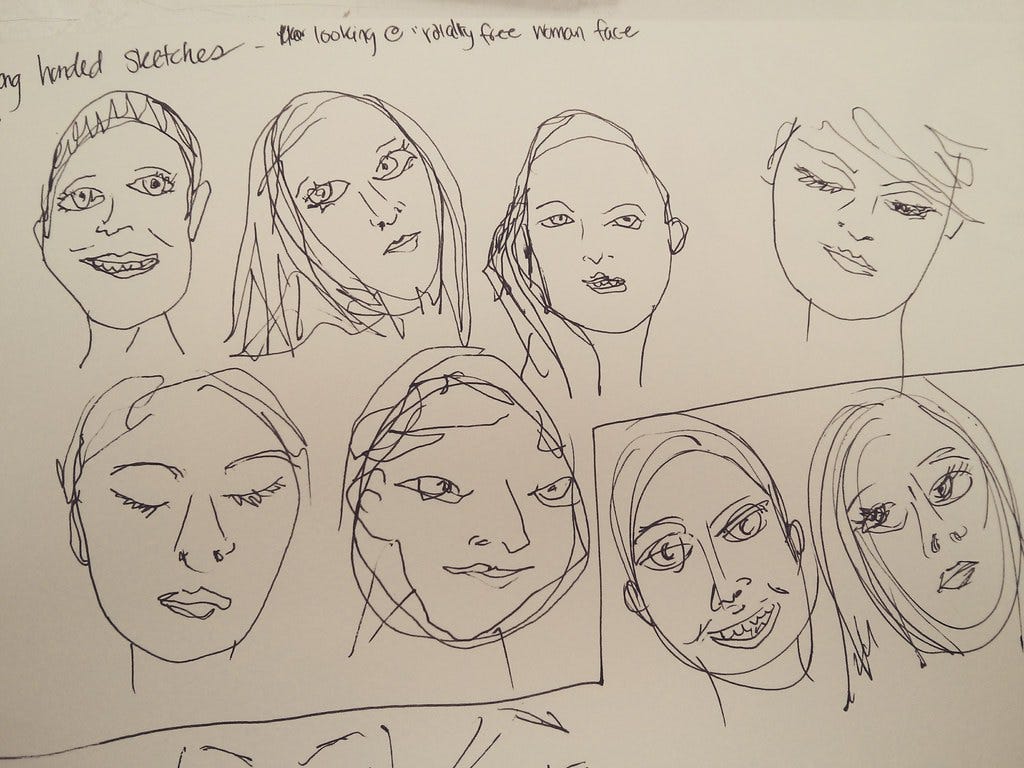

Last week I shared some maps that I drew in my notebook, while figuring out the world that the characters in my new novel lived in. Since then I’ve started playing around with sketching the characters themselves. I took a lot of art classes as a kid, but mostly we were taught how to copy other pictures—as a result I’m not great at original compositions, but I can do all right sketching from a photograph.

Taking fifteen minutes or so to do some sketching is good for mindfulness generally, but it’s also brought my attention to little details of the characters that I’m trying to now bring to the page: where shadows fall on their faces, how their hair sits (or doesn’t), the patchiness of a day-old beard, or the look in someone’s eye… all of this can be helpful.

Literally sketching the characters has been a nice reminder of where the phrase “character sketch” really comes from. In writing-world, we tend to use it for the kinds of rougher outlines that we do of a character before we put them into a story or a novel. Oftentimes this actually means going into far more detail than we eventually will in the final text—because we’re getting to know them (in some excess) ourselves so we can decide which parts really matter.

Jack Kerouac wrote thousands of little character sketches in his notebooks, just trying to get better at describing people through a form of automatic writing. It’s easy to do for just a few minutes a day—you can go outside, sit somewhere, observe passers-by.

And even housebound, we can practice.

A long time ago, I found this book of portraits by Richard Renaldi in my college library, and I made about two dozen color photocopies from it that I still use in classes, or just for myself. (You can find more of Renaldi’s incredible portraits here.)

You could write a hundred words about each of these pictures, and still have barely scratched the surface. You could write a hundred pages, and probably still have more to say. Every human being is an endless string of details (and this is all while we’re just staying on the surface!) and the trouble is that most readers won’t stay with that string of details for too long before they lose interest—in even the most interesting character.

So we have to sum them up in a few lines, or even just one really good line.

Wood calls this the “single brushstroke”: a perfect, simple, vivid description that tells us all we need to know about a character.

One of the all-time greats at this is author JD Salinger, whose penchant for summing people up perfectly in single brushstrokes is well embodied by his famous character Holden Caulfield (Red checked hunting cap? All we need to know to see him.)

Ironically, one of Holden’s many problems is that he makes snap judgements about people, based on some tiny detail (often behavioral) that stands out to him, and then can’t let go of. Writer John McNally points out many of them in an excellent essay, “The Boy That Had Created the Disturbance: Reflections on Minor Characters in The Catcher in the Rye”. There’s Edgar Marsalla who once farted in chapel, or Louis Shaney who always wants to know if you’re also Catholic, or a girl from a grade school museum field trip Gertrude Levine, whose hands are “always sweaty or sticky or something.” Jane, the girl that Holden is ostensibly in love with, he remembers because when they played checkers she’d always keep her kings in the back row.

We usually get little to no physical description of these people at all. Everyone’s defined by either a past action, or an ongoing habit of some kind.

Here’s Salinger describing Charles, younger brother to Esmé, in the story “For Esmé—with Love and Squalor”:

He needed a haircut—especially at the nape of the neck—the worst way, as only a small boy with an almost full-grown head and a reedlike neck can need one.

The narrator’s eye (and so our own) take in exactly the sort of very minor details we never remember in real life about the sorts of people we run into in coffee shops (like Charles in this case). That’s one reason why, when we’re given one of these in a story, we do remember it. Because someone else (the author/this character) has noticed it for us already.

Wood, earlier, pushed back against the idea of avoiding stereotypes in characterization. He doesn’t mean it’s cool to employ offensive stereotypes—assumptions about someone based solely on their race or gender or sexuality. He means that considering our characters as a type of person can be useful in characterizing them—because odds are, your reader knows someone else who is that type of person too.

She was a girl who for a ringing telephone dropped exactly nothing.

That’s Muriel Glass, from the opening page of Salinger’s “A Perfect Day for Bananafish. There are other excellent brushstrokes on that page, but this one does more than all the others combined. Twelve words and she’s alive. I know Muriel now, because I knew her before—that type of girl anyway.

In another Salinger story, “For Esme With Love and Squalor”, the narrator describes the soldiers in his group as “all essentially letter-writing types […] when we spoke to one another out of the line of duty, it was usually to ask somebody if he had any ink he wasn’t using.”

This is already a nice one, and he does even better by the end of the paragraph, describing himself: “Rainy days, I generally sat in a dry place and read a book, often just an axe length away from a ping pong table.”

By the time we get to the next paragraph and learn that he’s also tossed his own gas mask out of a porthole to make more room for books in his pack… we already know that he’d be the type to have done that. He’s real enough that we can start to assess his behavior and think to ourselves, “Oh, of course he would do that.”

In all of these examples, Salinger uses a generalized description, of the “sort of” girl or “type” of soldiers we’re dealing with. He outlines habits, patterns of behavior, because that’s how we understand people that we know a little bit.

This is another trick that comes from how our brains deal with the flood of people we meet in any given day, I think. We can’t remember a thousand individual human beings, but we can efficiently sort them into groups. And a writer can add a little life to a character by telling us what sort of person they are. We know other “letter-writing types” and girls who drop nothing for a ringing telephone, and those people come into our minds to help create the character we’re reading about.

Remember I said earlier that one of Wood’s complaints about bad characterization in fiction was that they’re presented statically, as if the author is describing a photograph and not a person? Well, it isn’t lost on me that this is exactly what I asked everyone to do earlier. But as Wood explains, the thing that must be done is just to get the character moving in some way or another. Describing habitual behavior almost creates a little montage in our minds—we imagine this person doing the same thing over and over again, across many years.

The ways Wood recommends getting past the static is just creating actual motion. He gives this example from a Maupassant story:

He was a gentleman with red whiskers who always went first through a doorway.

Perfect. A single brushstroke that does everything we’re talking about: a defining physical detail (red whiskers), a “type/sort of” grouping (gentleman), a habitual behavior, and… action. All in fourteen words. (We even get a contradiction/flaw, which we’ll talk more about next time… but basically, he’s a supposed gentleman who is actually pretty rude.)

In the novel Straight Man by Richard Russo, the main character Hank Devereaux is a writing professor, who leads his class at one point in a fairly standard exercise aiming at this same skill. He asks them to think of a person they know and fill in these blanks:

“I know you, _________________. You’re (not) the kind of man who_________________”

(And we can sub in “person” for “man” here, in the 21st century.)

“I know you, Muriel. You’re the kind of person who, for a ringing telephone drops exactly nothing.”

“I know you, soldier. You’re the kind of person who, sitting an axe length away from a ping ping table, will read a book instead.”

“I know you, gentleman with red whiskers. You’re the kind of person who always goes first through a doorway.”

That’s all it is. We can do it for our own characters easily enough—try it and see. It’s the spark of life.

(Russo does a very touching thing with this idea later in the novel. The professor has an epiphany that in life we all rely on “spouses and children and parents and colleagues and friends” to define ourselves in this same way “…because someone has to know us better than we know ourselves. We need them to tell us. We need them to say, ‘I know you, Al. You are not the kind of man who.’”)

You’ll notice that we’re already slipping beneath the surface layer a little bit here, and that’s perfectly fine. But in two weeks I’ll come back to Wood and his theory about the next layer of character, and we’ll start moving more inward—but as both Wood and McNally point out, lots and lots of great characters in literature never really get past this first layer. They’re essentially flat, to use EM Forster’s classic term in Aspects of the Novel… and as we’ll get into more next time, that’s actually not a bad thing at all.

For now I’ll just say that flatness works, certainly for the types of minor characters McNally identifies in Catcher, but as we’ll soon see—for lots of others. Arguably some of the most beloved and memorable characters in all of literature are totally flat. But like I said, we’ll get to that next time.

Until then!

Writing Towards the Fun #21:

This post already has a few fun assignments to it, but let me link them up here a little bit better:

Either go out looking for an interesting stranger to observe, or use a photograph like the Renaldi ones above. Write a little bit about them. Give them a name. What do they look like? What details stand out? Don’t worry right away about getting into things like their job or their personality—we’ll get there next week. And don’t worry about crafting a perfect single brushstroke. But after 500 words or so of description, take a look back and see if anything is starting to stand out.

Next, we play the Russo game. See if you can fill in the blanks for your character yet:

“I know you, _________________. You’re (not) the kind of person who_________________”If not, keep writing until you feel like you’ve got something that helps you see what type of/kind of person they are.

Now, turn that into its own little sentence—a single brushstroke for your character.

Hang onto all of this, because as we go deeper, we will get to “flesh out” these initial sketches into even more layered human beings.

And have fun!