Proust to Power

My plan for 2025

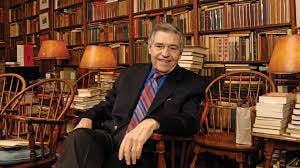

In college there was one class I wanted to take, but never did. The class had an innocuous title, The 20th Century Novel or something like that, and was taught by the famed critic Richard Macksey, who I knew a little through my job working as a GA in the Humanities Center department, making copies and shipping things for the various professors.

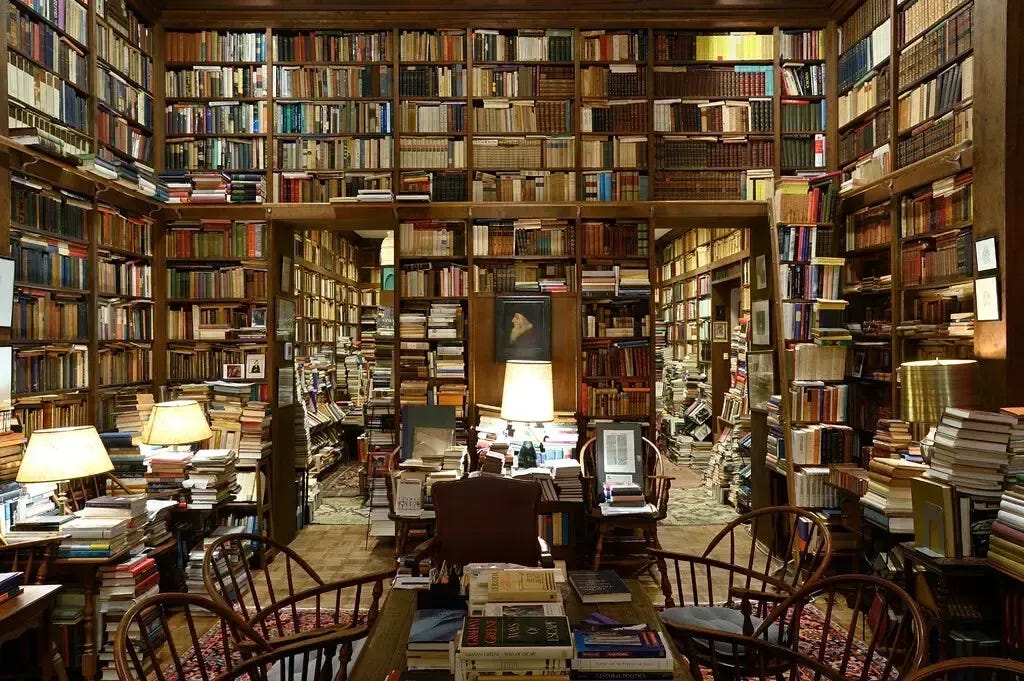

Macksey taught all his classes at his own house, a few blocks north of campus, in what was then the largest private library in the state of Maryland. At the department Christmas party there one year I was stunned by the sheer number of books—on floor-to-ceiling shelves, on tables in front of those shelves, in piles under the tables, etc. He had another whole room filled with films, in 35mm canisters. Someone told me that in a random bathroom he had a framed sketch of his (since deceased) wife on a cocktail napkin—notable in that it had been done by their old friend, Pablo Picasso.

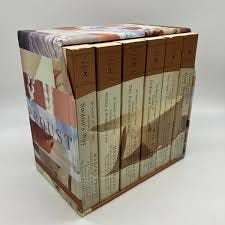

The 20th Century Novel, turned out not to be the typical survey of various important novels by different authors in that era. It was, instead, entirely focused on In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust, the 3723 page novel published in six (sometimes seven) volumes, published in French between 1913–1927 and first translated into English between 1922–1931. Macksey’s tiny seminar of students would read the work in its entirety over one semester—though they were advised to read at least the first two volumes over the summer before coming to the Fall semester, so that they had any chance of keeping up.

To me, now, this sounds like a dream. But back then I was intimidated (and not for no reason, I had almost been on academic probation a year before and was still pulling my GPA out of the gutter.)

I was all set to sign up for the class when a friend talked me out of it. He had done the class the year before and said that it completely hijacked his writing style— he’d found himself so drenched in those books that he had no time to read anything else. Suddenly he began writing all kinds of long, meandering, reflective, Proustian sentences and he said his workshop was in revolt over it. He seemed so gloomy and I was already so nervous about keeping up with the reading load, that I chickened out. I never took the class, and have long regretted it.

Macksey passed away in 2019 at the age of 87, and in 2022 there was even an article in the New York Times about how his library had become a viral sensation on social media. It has since been dismantled, sadly, with many of the 51,000 books donated to other libraries or sold off to collectors. I’m sure there must have been more than a few lovingly well-read copies of Proust among the shelves in there.

Over the years I thought about trying to sign up for a class on Proust, or digging in on my own. I bought a copy of the first volume of the Modern Library edition and tried a newer translation by Lydia Davis. I never got far into either. I was dipping my toes in, but never committing to doing the whole thing.

Then earlier this Fall, on a whim after I got a small surprise honorarium for a reading I’d done, I impulsively ordered the complete Modern Library set of In Search of Lost Time and put it out in my office.

A few weeks later, during a workshop class, an adult student of mine mentioned he was reading Proust for the second time. He’d been told that everyone should read it three times in their lives: once in youth, again in middle life, and once more in old age. I immediately felt annoyed with myself all over again, that I had missed that chance to read it in my youth—though I reminded myself that 20-year-old Kris would never have actually finished even one volume of it, given my struggles to keep up with my reading back in college in general. (During a class called The Age of Tolstoy I had to take an incomplete at the end of the semester when I was so far behind that I literally measured the reading I still had to do as seven inches high.)

Over the last twenty years however, and the last three especially, I’ve been able to finally pick up the pace with my reading—finishing plenty of 600+ pagers and some even bigger ones like War and Peace and Gravity’s Rainbow (OK, half of it) even. I knew that if I set my mind to it now, I could do it… but I still worried that it would eclipse everything else for months, maybe a whole year, and I would get frustrated by having to read Proust and only Proust all the time.

Finally, after the disappointment of the election in November, something clicked—or snapped?

Casting about for some way to weather the next four years of Idiocracy, I realized that all I wanted was to just plunge deeply into a world far from our own, a world of intelligence, music, wit, art, beauty, humor, pathos… everything I fear will be in shorter and shorter supply of as we endure four more years under the least literate President that the country has ever known.

At first I thought I could just slowly indulge over the next four years and read Proust, ten pages at a time, pacing myself through to the next election. But, doing the math, I soon realized that at that pace I’d be done with the book in just over a year. It isn’t long enough!

So I’ve settled on a compromise. I’m reading two volumes a year for the next three years, at ten pages a day, which will leave plenty of time for other books as well. I started a few weeks ago on Swann’s Way and have been really engrossed in it.

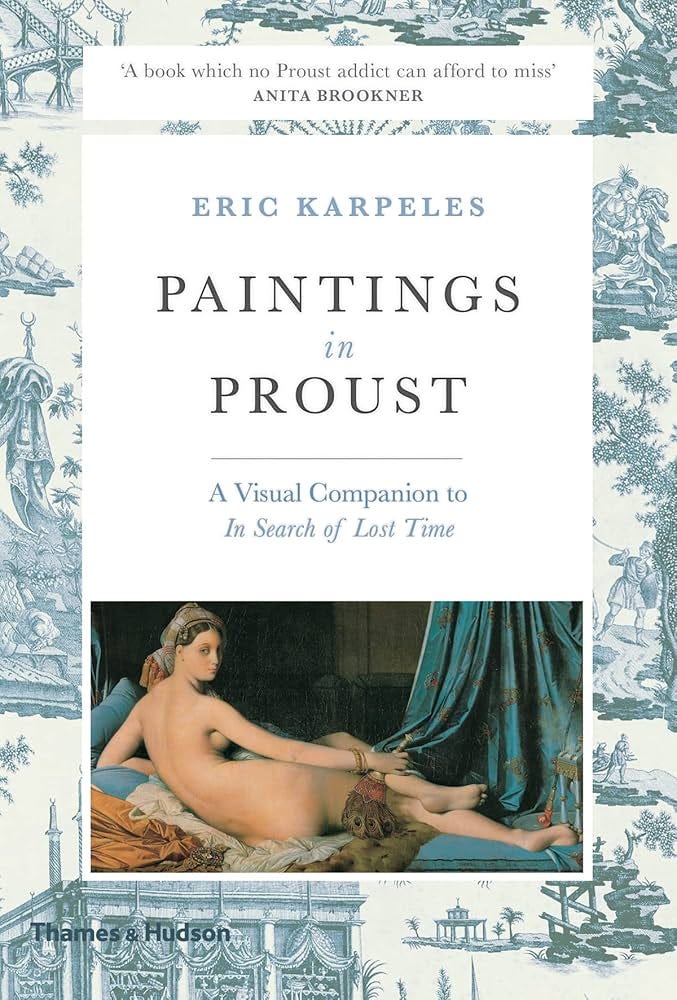

I’m taking notes along the way, reading companion essays in a book called Proust’s Way, and cross-referencing the visual art in a book called Paintings in Proust… and it has been, so far, a fantastic distraction from the present goings-on, and at the very least it is giving me something to look forward to over the next few years.

My hope is that, in addition to just being a welcome distraction, it'll be meaningful and even inspiring to just spend time with real beauty, and something that has endured for a century already, and this might even put contemporary things in perspective, or at least help me see it as a terrible patch in a long and varied history. I’m told that autocrats thrive on nihilism and impressing a kind of hopelessness on their subjects.

Maybe then if we can find anything to keep our sense of hope alive, we ought to do that as much as we can. Perhaps that’s some form of personal rebellion—speaking Proust to power. If great art requires some soul behind it, and in front of it, then it is something that the worst of them will never understand or appreciate, never be able to touch. They hate it because it will outlast them, and because even their cruelties will always be small in comparison to its joys.

On that note I also found a book called Year of Wonder by a British music critic Clemency Burton-Hill, where each day through the calendar year she selects a piece of classical music to listen to and read about, beginning with Bach’s Mass in B Minor and moving on in no particular order, to Mozart, Schumann (both of them!), Beethoven, Chopin, Poulenc, lots of choral pieces, some modern movie themes, and on and on. They’re usually 4-10 minutes long, and I have started listening to them in the morning just before starting the day’s Proust reading. Then, later, I will try to put the music on when I'm writing, and if I can, listen to the rest of the symphony or whatever it might be.

I'm hoping I'll have more to say about it as I move on in the books, and I plan on checking in here over the next few years. In the meantime, I'm hoping to get back to the original purpose of this newsletter in the new year, and focus on more helpful insights into bringing more fun into the creative process.

Here's to 2025, and beyond!

That's fantastic! I'm so happy to hear that you're loving it! I felt the same way after the first book and have been really moved now in the second! I keep wanting to start the next one but I'm worried now I'm going to get through it all too quickly! Let me know how it comes along for you! I'm planning another post soon with an update just on Proust! Cheers!

I took his class! Amazing experience (He was 88 when he passed away)