Today’s Writing Music: “Elevator Love Letter” by Stars

Today’s Reading: A Separation by Katie Kitamura

This week I’m pleased to have contributed to Catapult’s Don’t Write Alone, which dissects craft and the writing process.

Before you dive in here, check out that column, “My Name is Not Anna Stiedel” about a plaque I have had on the wall of my office for more than twenty years that does not belong to me—one of the ways I try to trick myself into confidence as a writer.

In that piece, I quote Zadie Smith in her essay That Crafty Feeling:

“It’s such a confidence trick, writing a novel. The main person you have to trick into confidence is yourself.” And I’d like to expand on that idea a little bit in this week’s newsletter.

One reason con artists are so appealing in literature and other forms of entertainment is because they mirror the reading/viewing experience.

Take any good heist movie like Ocean’s 11 or a TV show like the BBC’s Hustle, where a gang of con artists skillfully trick rich jerks out of their money. It’s fun to watch them outsmart casino owners or crime lords. Often, this is done by taking advantage of their massive egos in some way, seducing them, exploiting a weak spot. We enjoy watching a skillful craftsman creating the alternate reality that diverts their mark.

But when I’m reading a novel (or watching a show/movie) I’m the mark—being conned (willingly) by the storytellers into believing in a carefully constructed alternate reality, and getting so invested in it that I’ll gladly spend hours of my life in there. The difference here is that I’m a willing participant—hoping, in fact, to be fully swept away by the writer.

Zadie Smith’s observation that a writer must also con themselves points in the opposite direction, but is just as valid. The art of the con applies not just to reading, but to writing. (In the Catapult essay, again, I discuss how hanging another person’s award in my office became a way to outsmart myself, and to stoke my own ego too, in an effort to trick myself into thinking I, too, would one day be a successful writer.)

When we read (or watch) The Talented Mr. Ripley and see Tom taking on new identities and gaining people’s trust for his own selfish ends—we’re also enjoying a metafiction about the writing process as we noted earlier. Patricia Highsmith puts us in Ripley’s shoes. He gains our trust by confessing all kinds of intimate things to us, so that we love him and root for him—even as he’s slyly insinuating himself into the lives of others with his own lies (as she’s insinuating him into our lives, etc.)

But the Zadie Smith line is a reminder that this works in the opposite direction as well.

In order to con us into aligning with Tom Ripley and his tricks, Patricia Highsmith first had to con herself into sitting down and writing the book.

According to a book called Daily Rituals: How Artists Work by Mason Currey, Highsmith did this by developing a routine that worked best for her. She wrote every day, for three or four hours at a time, aiming for around 2,000 words. But to make this feel less like scheduled labor, she needed to trick herself:

“Her favorite technique to ease herself into the right frame of mind for work was to sit on her bed surrounded by cigarettes, ashtray, matches, a mug of coffee, a doughnut and an accompanying saucer of sugar. She had to avoid any sense of discipline and make the act of writing as pleasurable as possible.”

Recently, in the New York Times Magazine, writer Ingrid Rojas Contreras shared a strategy for using techniques of self-mesmerism to overcome anxiety and PTSD while writing. She selected a specific item of clothing, in a certain shade of blue, that she wears for ten minutes each day while imagining herself in a place apart from intrusive thoughts, before launching into her writing for the day.

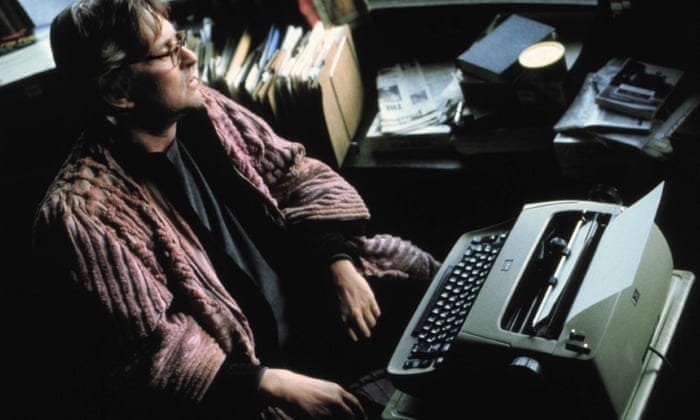

Reading this, I couldn’t help but think of Grady Tripp in Michael Chabon’s novel Wonder Boys, and the dirty pink bathrobe he wears habitually while writing. (Below, see the character as embodied by Michael Douglas in the equally wonderful film.)

Whenever someone asks Grady to explain the story behind the bathrobe, he demurs, saying simply that it isn’t very interesting. Perhaps it is nothing more than the way he suits up for work each day—just like Contreras’s “muted ultramarine” slip.

Contreras writes that, wearing the slip, or other items of clothing in this specific hue, she can at last achieve “a floating between presence and absence, a sense of stillness, awareness and listening.”

That, it seems to me, is a big achievement—every writer has other jobs, family obligations, health concerns, financial stresses, household responsibilities… not to mention a host of basic existential doubts and fears. The rejection and disappointment we face can weaken our confidence, and shatter the delicate flow state necessary to create art.

The most recent Disney/Pixar movie, Soul, involves a jazz musician named Joe, who slips into a coma after an accident and travels to a realm between life and death. The movie is billed as being about the after-life, but I was far more fascinated by how it depicts creativity.

Because the in-between place that Joe’s soul goes is, in the film, also be the place where someone’s soul goes while they’re fully absorbed in some art or practice.

Joe sees the “flow” souls of tattoo artists, basketball players, actors, and even just people dancing in the park, and later in the film Joe will achieves this same state while performing.

And here’s the connection… achieving this flow is tied closely to confidence.

Writing (like all art) involves making a million little decisions, over and over. How do I phrase this? Long sentence or short? Is there a better word to use here? How do I define this character? Can anyone see that setting? Does this plot twist work? Does that line of dialogue sound right? Is this a run-on sentence? What if put in a semicolon? etc. etc.

On bad writing days, we labor hyper-consciously over each of these decisions, doubting ourselves, getting distracted, and ending up nowhere good.

But in a state of flow we make these decisions more instinctually, trusting our muscle memory to do its job. (Writers, at least, have the chance to fix almost anything later in edits—untrue for Joe when he’s performing live in a jazz club.)

And our level of confidence matters not just in getting the work done, but also in the ultimate quality of that work.

Recently, I watched a MasterClass video lecture on writing by novelist Amy Tan. In one part she discussed the opening of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera:

IT WAS INEVITABLE: the scent of bitter almonds always reminded him of the fate of unrequited love. Dr. Juvenal Urbino noticed it as soon as he entered the still darkened house where he had hurried on an urgent call to attend a case that for him had lost all urgency many years before. The Antillean refugee Jeremiah de Saint-Amour, disabled war veteran, photographer of children, and his most sympathetic opponent in chess, had escaped the torments of memory with the aromatic fumes of gold cyanide.

Tan points out the confidence exuded by Marquez in this passage… beginning with the very bold claim, “It was inevitable” and going right down to the “aromatic fumes of gold cyanide.” Marquez has to make us believe that Dr. Urbino knows this about gold cyanide (that it smells like bitter almonds), which means Marquez has to make us believe that he knows it, which means he has to believe he knows it…

Get it?

Tan puts it this way: “Everything that this writer knows, that he had this narrator know, every single detail communicates something about the time or about what this person does, possibly about the setting by the nature of the names, about a sense of history, about what he means by ‘love.’”

The con artists in the movies use a mark’s ego against them. For a writer, conning yourself usually works the same way—you have to tease that ego out as much as possible. Convince it to trust you.

It is a monstrous act of ego, to write a book. I, as much as anyone, like to do the shoe-gazey, humble, aww-shucks thing whenever possible. “I wrote a thing” I’ll post on social media, as if I sort of stumbled ass-backwards into it, as opposed to working deliberately on it for weeks or months or years. This is just a cover for the embarrassing amount of ego involved.

To write a book you need to believe that someone else needs to know what you think about something—love, life, sex, work, death, grief, joy. You have to believe that you know something they don’t about these things, and more often than not that means tricking yourself into believing that you do.

But the thing is, you do—if you’re writing, then you’re spending your time engaging in these questions, sifting through memories, doing research, etc. etc. You’re looking at it all a lot more closely than most people can afford to.

You just need a little trick to remind yourself to believe it.

Zadie Smith hangs little quotes from books she admires around the room. Haruki Murikami writes all morning and then run a 10k every afternoon (he makes us all look bad). Maya Angelou keeps a deck of cards and some crossword puzzles nearby (but can’t have any paintings or decorations on the walls). Ernest Hemingway tracked daily word counts on a little wall calendar. Kurt Vonnegut liked to do push-ups and sit-ups. Ian McEwan takes long walks. Jack Kerouac would light a candle, and blow it out at the end.

Little rituals and routines. Self-mesmerization. Confidence tricks.

Some like a crowded living room or a bustling café. Some need total reclusion and silence. Some write in the mornings, some write in the middle of the night. Whatever works for you is what works for you.

Mine are pretty simple: I make a cup of coffee each day before sitting down to write. I grind the beans a certain way, boil the water to a precise temperature, pour it through a specific filter. It’s silly, maybe, but it works (most of the time). I take off my watch and my wedding ring—not for symbolic reasons, but just because I need my hands free. Certain familiar music gets things flowing. I have a second laptop that can’t go on social media at all for when I’m being really undisciplined.

When the weather is nice I like to sit outside on my porch and work, but first I have to sweep it completely clean from end to end with an orange broom. (I have a leaf blower that could accomplish this task in about a tenth of the time, but the sweeping is part of the process.) I use a specific pen (Pilot Precise V5 Extra Fine) that I’ve used religiously since middle school. Time of day depends on various factors in the rest of my life—if I’m teaching, if my kids are sleeping through the night, if I’m busy, etc.

There’s more, but I’ll spare you—like Grady’s bathrobe, I have to say, it’s not very interesting. What matters is consistency. The more days in a row that I can stick to the routine, the better it tends to go.

So make yourself a little Pavlovian trick, and dupe yourself into believing (really trick yourself out of doubting) that you can write, and write well. Do it confidently, no matter how many things are going on outside of it.

Writing Towards Fun #6:

Make a list of any rituals or habits that help you write successfully. Where do you go? What do you listen to? What do you like to eat/drink? Do you wear a specific item of clothing? Have a lucky charm nearby?

Once you have that list, commit to it for an entire week. Do everything you can to write at the same time of day, or in the same place.

By the end of the week, did you find it easier to get into a “flow” state?

What challenges arose in maintaining consistency?