Today’s Writing Music: “Believe” (cover of original by Cher) - Me First and the Gimme Gimmes

Today’s Reading: Not-Knowing: The Essays and Interviews Donald Barthelme (Author) Kim Herzinger (Editor)

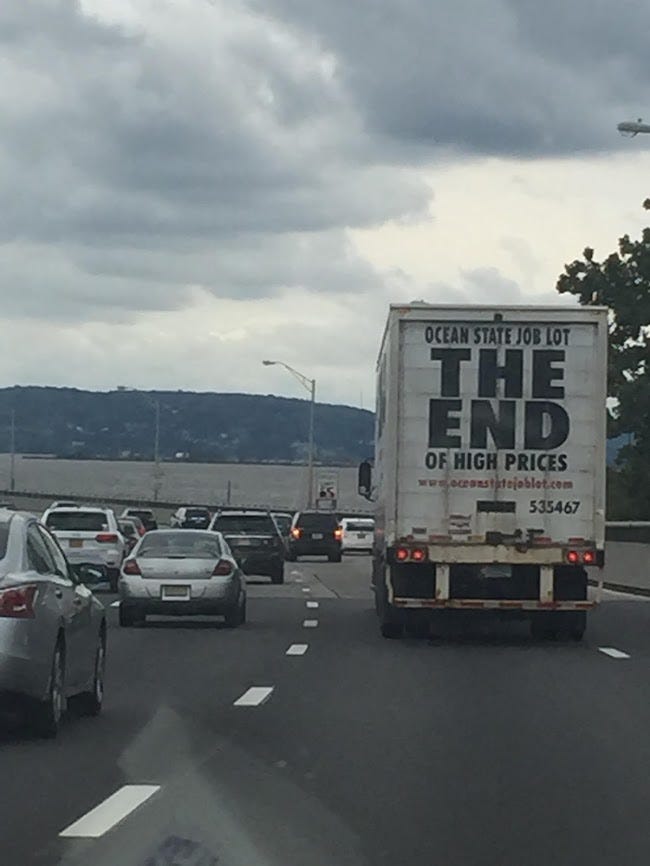

A few years ago, as I struggled to wrap up my second novel, Why We Came to the City, I got stuck in traffic behind the truck in the picture above. I felt… mocked. Literally trying to get ahead in a mess of cars going over the (then) Tappan Zee Bridge while THE END dangled ahead of me. I texted this photo to my agent and editor in desperation.

The book was done. It just didn’t feel like I’d found, well, The End.

Even before this, I had written an op-ed in The New York Times called “The End, or Something” discussing how difficult it is to know when a piece of fiction is really finished. There’s always more you can add, of course. Even in Hamlet, I argued, where almost every character dies (spoiler alert) you could still go on about old Fortinbras getting out a mop and cleaning up all the bodies. In short fiction, I’d been taught that it was good to end things on an ambiguous note, with big things still lingering in the reader’s imagination. I joked that this left me with the sense that a good ending should be like George Costanza leaving a meeting on Seinfeld. Land your punchline and get out quick.

In that article, I confessed how when I sold The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards, I’d considered it fully done—if I hadn’t, I never would have sent it out to publishers in the first place. Only to learn, as I met with my editor that she didn’t think it actually was done. And not that it needed tons of editing or revision. She just thought I’d leaped out too early. Written “THE END” after a chapter where the main characters had been reunited in friendship… but where you really had no idea what would become of them after.

In any case I soon saw that what she meant and wrote a whole new chapter, which was then added in. It is now one of my favorite parts of the novel. (This is the chapter “King Me” for any OG fans out there.)

Still it haunts me a little—we fixed it in plenty of time, but how had I not realized that I hadn’t really ended the book? I’d worked on it for years!

In that same article, I talked about some ways I teach endings in my creative writing classes. There’s Aristotle’s Poetics: “an end […] is that which itself naturally follows some other thing, either by necessity, or as a rule, but has nothing following it.”

This is not super helpful though, no offense to the great philosopher… what does he mean by “naturally follows”? What constitutes a “necessity” or even “a rule”?

A craft essay from the Gotham Writers’ Workshop suggests that a story is over when the “major dramatic question” has been answered: yes, no, or maybe (if neither yes or no will be satisfying). This works, but it can be a bit basic. You can’t merely solve the crime, find the missing dog, break apart the couple, get the couple together, etc. etc. etc. That’s the beginning of an ending, I think. But we want something more.

The maybe, or the ambiguous ending, is popular in literary fiction because it allows space for “more” to evolve in the reader’s imagination. We can ponder the deeper meanings, even after the Misfit kills off the last of the family in Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” When the killer says, of the Grandmother that she “would've been a good woman if it were someone there to shoot her every minute of her life,” O’Connor leaves us space to interpret the broader implications. And reams of paper have been spent in doing so in the fifty years that followed its publication: The Misfit is God, the Grandmother represents Jesus Christ, it is about the nature of violence, the nature of Grace, etc. etc. etc.

In “The Nature and Aim of Fiction” O’Connor says that to increase the meaning of a story, a writer must develop their anagogical vision:

"[…] that is the kind of vision that is able to see different levels of reality in one image or one situation. The medieval commentators on Scripture found three kinds of meaning in the literal level of the sacred text: one they called allegorical, in which one fact pointed to another; one they called tropological, or moral, which had to do with what should be done; and one they called anagogical, which had to do with the Divine life and our participation in it. Although this was a method applied to exegesis, it was also an attitude toward all of creation, and a way of reading nature...

O’Connor reminds us that a completed work of fiction makes meaning on multiple levels: literal, moral, Divine. But how does a writer pull this off? Am I supposed to know all of this from the get-go when I’m writing? Am I supposed to have a map somewhere in my Documents folder that spells it out with little subheadings, like Cliff’s Notes to my own book? Allegorical, Tropological, Anagogical?

No. I don’t think it works that way, at least not for most of us.

We can only write towards an ending that satisfies us on all these levels, but we don’t typically know what they all are until we’ve written it. In fact, I bet most of us couldn’t tell you what they are even after its been written. And rewritten. And rewritten.

Novelist Elizabeth Bowen, in her Notes on Writing a Novel, tells us that we must move toward “an end not to be foreseen (by the reader) but also towards an end which, having been reached, must be seen to have been from the start inevitable.” There should be some component of surprise to an ending, but then it must also feel like it is the only way it all could have gone. That's quite a trick… and I think it is both true and the reason so many exciting books blow us away at the start and then fall apart by the end. It may well be the hardest thing there is to pull off in all of fiction writing.

Are you a “plotter” or a “pantser”? one popular internet meme asks. Plotters work out their whole novel in an outline before they begin. A Pantser (as in flying by the seat of your…) just wings it and hopes they can work it out along the way. Personally, I've always been a “pantser” though I prefer the term “micro-manager”, coined by Zadie Smith in her essay “That Crafty Feeling” where she describes the divide as being between these and “macro-planners.” (She’s a micro-manager, like me.)

It’s been this way from the start. As a kid, I thrived on that sweet, sweet panic of procrastination. Teachers would urge me to map out my research paper on little index cards, give me weeks to prepare… and I'd do it all on the last day. If we had to turn in the index cards, or an outline, I’d manufacture these after the fact, based on whatever I'd written already. I hated being told, show your work.

The thing is, I wasn't lazy. I just really loved the thrill of spontaneously working it all out in the heat of the moment. I loved that feeling of discovery and I still do. (When I teach classes or write these newsletters, I usually have a vague idea of where I’ll aim and one or two things I’ll hit along the way. But the fun part is watching it come together as I go, making those connections on the fly and surprising myself in the process.) The panic and the pressure would always lead me to something that truly surprised me. Something I was sure I could never have seen in an outline before I’d started. And this was the best way I knew to get to what Bowen described: that which is surprising at first, and seems inevitable after. (Think of O’Connor’s Misfit again. We’re shocked when he murders the Grandmother, but in the end, it seems to have been unavoidable.)

My first stories were often based on imaginary scenarios my elementary school friends and I had enacted during recess. We'd play Superheroes, and I'd rush inside for “journal time” and write down every twist and turn before I forgot. Later, in middle school, I wrote my first “novel” with my friend Dave. Like those recess stories, our novel was mostly a dramatized accounting of our AD&D games: all the fun plot twists that arose as we played. Again, there was an element of surprise to it, of improvisation. Though Dave, as DM, had outlined things without me being aware. So the novel we wrote together was, in a sense, pre-structured but in a way I was uninvolved with.

Later in college, I tried writing long things on my own—screenplays, at first—and discovered the need for both outlining and not procrastinating. I could crank out a killer 12-page story in one all-nighter right before workshop… but I couldn’t do that for a 120 page script. Reluctantly, I turned to those methods I’d once scorned. I soon had a huge wall in my bedroom filled with colored notecards, tracking the scenes in multiple plotlines in my magnum opus, “2:37 AM,” and I had to break that project down into steady work. The script, and the movie we finally made that summer, taught me so much about outlining and breaking down a story. These would be essential to my stab at a real grownup novel the following year.

Except… that novel fell apart. By the time I got to the end of it (335 pages later) I was so bored with it that I never looked at the file again.

This, then, is the conundrum. Writing something big takes planning and steadiness. But figuring it all out too quickly can suck all the excitement out of it. If the work ends just where I expected it to, I’m disappointed (and so is a reader.)

“No worthy problem is ever solved me within the plane of its original conception,” I’ve been taught—this quote is from Albert Einstein, though I’ve seen it written often as, “No problem can be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it.”

We may write with a plan in mind, or without one (more on this in a bit) but in any case I think we are always hoping that, along the way to “the end” much will come to us that we couldn’t see initially. That the project will become far better and far smarter, and more interesting than we could have predicted at the start.

Milan Kundera wrote that, “Every true novelist listens for that suprapersonal wisdom, which explains why great novels are always a little more intelligent than their authors. Novelists who are more intelligent than their books should go into another line of work.”

Sometimes it can seem like the entire writing process is really a long gamble, an extreme test of our own faith in ourselves, that this suprapersonal wisdom will arrive, (or emerge?) in time for the ending.

We could call it “divine inspiration” and surely many people have, and I do consider it to be something quasi-holy. I’ve written before about Elizabeth Gilbert’s TED Talk “Your Elusive Creative Genius” where she reminds us that for many millennia, a “genius” was not a person but some mystical entity (like a muse) that came to live in the walls of an artist who was receptive to it.

She laments that as artists have become less mystical/more secular they’ve taken a more intrapersonal view of great wisdom. Post-Freud, we’ve been taught that wisdom comes from wihin, the result of our own honest and relentless probing of our subconscious. Or if it will be found externally then it must stem from deliberate, highly-astute observations about the people and the patterns in the world around us (see: Serious Noticing).

Either way, we tend not to think it is God Almighty or even a diaphanous muse who directs us to the big idea, whether it is inside of us or at the supermarket. Even if it is suprapersonal, it isn’t supernatural. (Gilbert disagrees, and in her book Big Magic she discusses great ideas as being almost like fairies that fly around and might land in your head if you’re open to them. Who am I to argue?)

George Saunders’s A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, offers another possibility that I like a lot, something that seems to lie nicely between the extra— and the intra— and the supra—. Saunders points out that Kundera’s quote about suprapersonal wisdom comes in the midst of an analysis of Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy. An early draft of that masterpiece apparently is much harsher in its judgements on Anna’s infidelity, and Kundera notes that Tolstoy himself could be a moralist (though, as Saunders points out, one who did not always hold true to his moral edicts).

Kundera says that Tolstoy’s changes over the many drafts he wrote of Anna Karenina don’t suggest he “revise[d] his moral ideas in the meantime” but that the “wisdom of the novel” became “another voice” to which he chose to listen as he worked.

Saunders explains that this suggests that “the writer opens himself up to that ‘suprapersonal wisdom’ by technical means. That’s what “craft” is: a way to open ourselves up to suprapersonal wisdom.

In this view, the source of wisdom isn’t a God or a muse. Neither is it always buried deep in our own psyches, nor is it always out there in the world waiting to be noticed… the wisdom resides in the process of the writing itself. (It occurs to me that Saunders is a Buddhist—and that this perspective on where wisdom comes from seems like tothe way someone who practices daily meditation might think about it.)

In the case of Tolstoy, writing Anna Karenina took four years of dedicated work, multiple drafts in which the 864 page book was rewritten nearly entirely each time. And in that time, and with that work, Tolstoy got to know his creation better and better. As he fleshed Anna out, and then farther out, and then farther out… he developed more and more understanding of her, sympathy for her, even belief in her. And as that continually happens, Tolstoy became capable of seeing more than he could see before. The same way we might if we make a new friend in real life, whose experiences show us new things about the world.

Yes, it still seems a bit mystical—after all, we’re creating the friend, so how can she show us things we didn’t know before?

Again, Saunders would remind us, it isn’t really Anna sharing wisdom with Tolstoy, it’s the process of crafting Anna that revealed all this wisdom to Tolstoy—and, so it can reveal itself to us as we work.

When we’re sitting and crafting, we’re communing with a veritably ancient creative process, which has carried generations of artists along towards wisdom since the beginning. So it has a bit of a spiritual vibe to it, for all that.

What do we mean by “crafting” then? It’s decided unmystical on its surface. Craft is nuts and bolts, meticulous work. Outlining a plot, yes, but also moving commas around, rewording a description, eliminating overused words… Craft is: rules, methods, practices, ways and methods of plodding along towards creation.

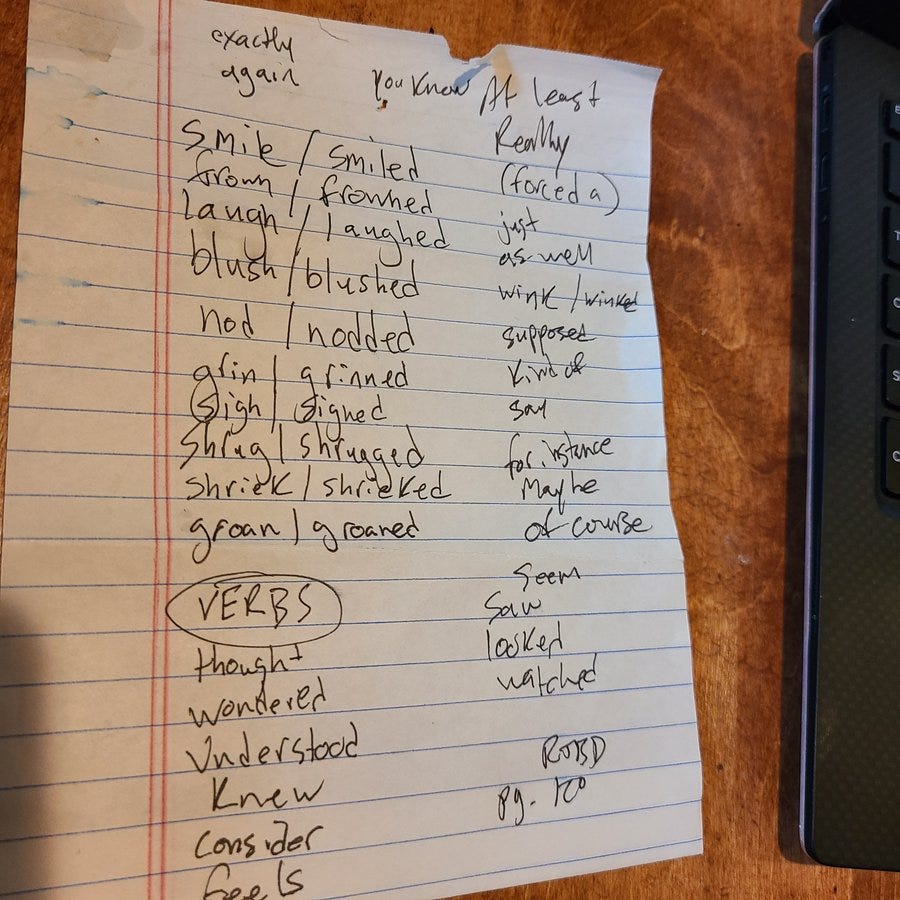

This morning I finished a two-week revision of a 330 page novel manuscript which has consisted of nothing but taking fifteen to thirty pages at a time, moving them to a new .doc file, scanning them for every instance of a set of words I use too much, and one-by-one eliminating them, or replacing them, or keeping them.

And as I did this, I wondered (oops) to myself if Tolstoy sat around with 864 pages of Anna Karenina, hunting for the overuse of “maybe.” (Or “может быть.”) And my inclination is to think that, no, of course (oops) he didn’t—he was simply a genius, who just (oops) naturally wrote in a perfect, precise style with no need for the kind of hunting and pecking I require to fool readers into thinking I'm smart.

But this is surely not true. Not only did Tolstoy surely do the exact same tedious thing I was doing, but he did it long before electronic find-and-replace was an option.

That’s craft, and it’s also a pretty powerful continuity to be part of. And I think this is why it leads us to such suprapersonal wisdom in the end. Endless questioning. Timeless repetition. Shared process. These can take us outside of ourselves in some way, or perhaps inside of ourselves. It helps us see more clearly what we’re saying, feeling, and thinking.

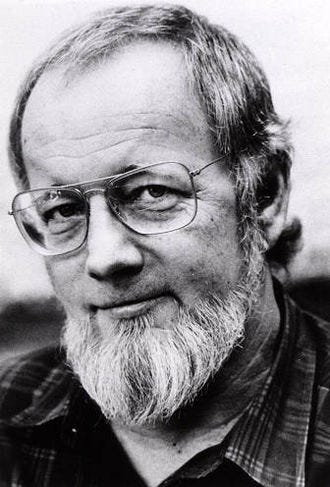

In an essay called “Not-Knowing” the writer Donald Barthelme discusses the importance of this open-ended seeking in the artistic process. He describes a writer setting up the beginning of a story involving a gold pocket watch, a thief in a chastity belt, an azalea bush, and two Sarah Lawrence students named Jacqueline and Jemima who have just failed their GRE exams.

“What happens next?” he asks.

“Of course, I don’t know,” he answers. Then he elaborates, “It’s appropriate to pause and say that the writer is one who, embarking on a task, does not know what to do.”

In Barthelme’s process, elements are mixed together in a story like chemicals in a laboratory, and then a writer just sees what happens. His best stories proceed from seemingly nonsensical premises: “I Bought a Little City” is about a wealthy man who buys Galveston, Texas and begins rebuilding it as if he is a god. “The Balloon” is about a man who inflates a massive gray balloon over Manhattan without much explanation as to why. One of my favorite stories of all time is called “Some of Us Had Been Threatening Our Friend Colby” and launches off from this unforgettable pair of lines:

“Some of us had been threatening our friend Colby for a long time, because of the way he had been behaving. And now he'd gone too far, so we decided to hang him.”

A Barthelme story seems to proceed almost haphazardly, line by line, as if it is being made up by him as you’re reading it. But of course it isn't haphazard at all. The Craft of fiction requires things bear some verisimilitude. Urges him to reject first-order solutions. Drives him to an ending that satisfies on multiple levels. There are a ton of rules!

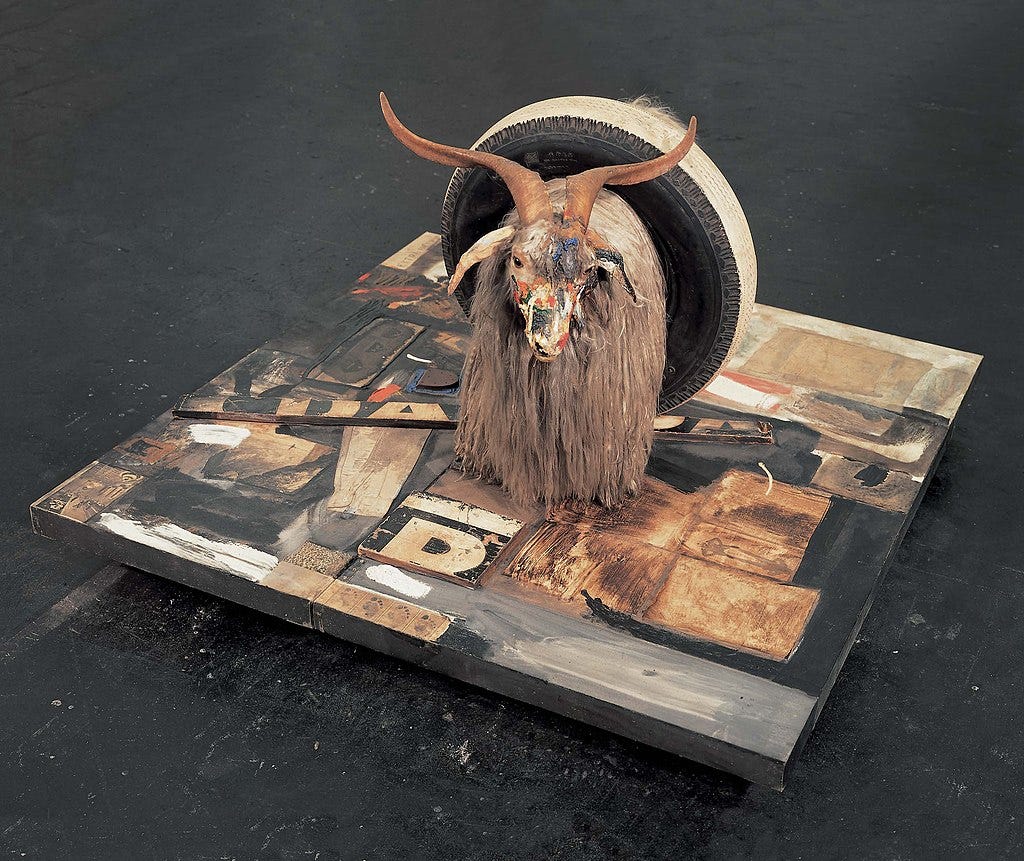

In his essay “Not-Knowing” he discusses Monogram, a Rauschenberg sculpture where a goat sits in a tire. Why? He doesn’t know. Neither did Rauschenberg. The artist bought the goat at a Seventh Avenue furniture store for $15 and it took him four years and three attempts to work out what to do with it before putting them together in Monogram and feeling like they worked. (He only found the tire in the second “draft”.)

Why was this the final state of the project, and not the previous ones? Why does a tire go with a goat? What does it all have to do with a monogram? What happened here that made Rauschenberg sure that he did not need to go on to a fourth version?

In other words, how did he know he was done?

You can read as much art criticism on Monogram as you can literary criticism on “A Good Man is Hard to Find” but in the end those will all only tell you what these things mean to other people. What’s clear, though, is that they came to mean something definitive to their creators. They found that sweet suprapersonal wisdom there, at the end of the long road of Craft.

Tolstoy’s novel exceeded his original moral view of Anna, and was not finished until it at last lived up to the beauty and complexity of the character he’d created.

O’Connor’s story was finished when it at last came to satisfy her “anagogical vision.” The Anagoge in ancient Greece was that which climbed upwards. A good ending reaches beyond what seemed originally possible. If you’ve come to the last paragraph and merely achieved what you imagined at first, you’ve still got a ways to go.

“Writing is a process of dealing with not-knowing,” Barthelme writes, “a forcing of what and how. […] The not-knowing is not simple, because it’s hedged about with prohibitions, roads that may not be taken. The more serious the artist, the more problems he takes into account and the more considerations limit his possible initiatives.”

I think this reminds us that with all the reckless freedom of beginning our experiments, jumping off from some great premise or opening line, the way forward is defined by all the limits and problems that Craft teaches us to address. Steadily that path becomes less of a glorious mess of potential energy, and lands in a specific resting place. Wherever “The End” is, I can only say that it is somewhere higher than you thought it was. It’s however far you can reach, and then just a little farther.

The day I finally sent in the absolute last copyedited manuscript of my second novel, I was walking down Second Avenue when I saw a giant mural of a dinosaur on a building wall. It rhymed, in my head, with something else (the opening of Bleak House) and I veered off into a coffee shop and busted out my laptop. In thirty minutes, I wrote a new, short final section to my novel, titled “The City that Is,” and immediately, armpits damp with panic and pressure, emailed it to my editor begging him to add it to the end.

And then I finally knew—I had it.

Writing Towards the Fun #31: To my point about endings always being a place from which more can proceed, here’s a fun little exercise. Pick a book off the shelf, or a story from your library, and flip right to the end. Grab the final line (or at most two lines) and copy them into a new page or document. Forgetting the context around that line in the original story, treat it as the opening line of your own new story. What are the problems it introduces? What are the roads that can be taken? Write until you find a new ending. (And then tomorrow, could you start over from there?)

Here are just a few taken from The Anchor Book of New American Short Stories, if you don’t have anything good handy:

“Every time I say I don’t know. And I don’t.” (From “Sea Oak” by George Saunders)

“But still you wake up late at night and lie there listening for the creak and splash of oars, the clank of steel, the sounds of men rowing toward your home.” (From “Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned” by Wells Tower)

“‘He is not paralyzed. I am his wife, I am a doctor. I would know if there is something really wrong.’” (From “Do Not Disturb” by A.M. Holmes)

“With the amazing turns of her hips, and the warmth of the music inside her, did she believe, for even one glorious second, that her passion had arrived?” (from “The Girl in the Flammable Skirt” by Aimee Bender

“He walked over to the window, a vista of sky, brick. ‘Don’t be with me,’ said Gary.” (From “I’m Slavering” by Sam Lipsyte)