Last month I talked about the importance of titling stories, and how integral a good title can be to the writing process—so much so that I often find myself thinking of titles before I even really have much sense of the story that might fit it. I’ll encounter a phrase or a word that just has an aura around it—right now in my notebook I have a list of several that just feel like they have potential to me: “The Calumny of Apelles” (which is already the name of a painting) and “Relatively Sound Mind and Body” as just two examples. I don’t know if I’ll end up using them, but just rolling those words around in my mind is exciting, and day by day I sometimes feel as if I’m on the lookout for a story to go with them. It’s like having a quick look at the picture on the puzzle box before beginning a hunt for the pieces.

But when it comes to naming my characters I often have an almost polar opposite experience. Who are they? They could be named almost anything. I find it incredibly overwhelming. I have a story in mind, or a voice at work, but I have no idea whose story it is, or what the name of the speaker might be. Mark? Rahul? Nicole? Juniper? Charlotte. Benji. Giovanni. Beatriz. I can go on and on like this, with none jumping out at me as being particularly right or wrong. It’s one of my least favorite parts, to the extent where I often lean into the complexities of first person narration largely so that I can have an unnamed narrator… but even then I have to name their friends, family members, every random minor character. I tell myself that there aren’t really right or wrong answers, and to just trust my gut like I do with titles. But for some reason the same instincts just won’t kick in. It’s just utterly overwhelming to me.

As Matt Bell observes in his excellent and trusty guide, Refuse to be Done, a character’s name—at least the main character’s name—is likely to be one of the most frequently used words in your novel. (Comparatively the title is just there once, usually, lurking in the back of a reader’s mind—more of an organizing principle than a frequently used expression.) If you name your character “Betsy” or “Eric” or “Fatima” or “Sandra” then you’re going to be typing that over and over and over. The music (or not) of that name is going to become a part of the rhythm of sentences in virtually every paragraph. It becomes hopelessly central to the patterning of your story or novel, the same way that our own names become absolutely central to our own sense of self.

And I wonder if, perhaps, this is part of the struggle. After all, with rare exceptions, most of us in the real world did not choose our given names—unless we’ve had them legally changed for some reason. Even then we would have lived out our formative years with a name that was chosen for us, often before we’d ever breathed air or seen light. Our parents—facing a perplexingly similar challenge to fiction writers—choose names for us and we then live our lives within the invisible bounds.

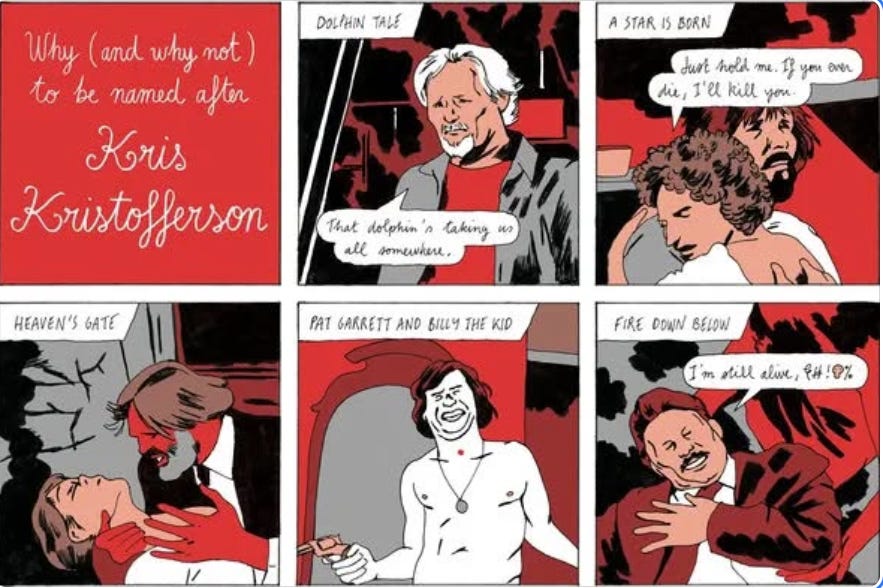

Perhaps you think I’m being a bit dramatic here—and maybe I am. Many years ago now, I wrote about my personal journey of understanding with my own name. In brief, my mother named me “Kristopher” after the actor Kris Kristofferson, in part because she’d loved his performance in the film A Star is Born with Barbara Streisand. I found this very perplexing as I got older, even a little embarrassing, because I only knew Kristofferson as the grizzly vampire hunter in the Marvel movie, Blade. It wouldn’t be until college that I’d discover that he was many things beyond that: a Rhodes Scholar, an Army helicopter pilot, a county music star, and the writer of the Janis Joplin classic Me and Bobby McGee. Eventually I actually sat down to watch A Star is Born as was shocked to discover that the character Kristofferson played (John Norman Howard, which I have to say, as names go, is a bit forgettable) was a selfish, drug-addicted, and suicidal rockstar—quite a disconnect from the guy that my mother actually made every effort to raise me to be!

Of course, over time, I made the name my own, including its origins, and now would never part with it. But the point is that my character grew out of it, and perhaps at times against it, as I developed… just the way it might for a character in a novel or a story. If I call them “Jasper” or “Richard” or “Ellison” on page one, won’t that affect, in some ways, the sort of person they turn out to be in a story? By the end of the book I couldn’t imagine, for instance, going back and totally reinventing a character’s name. Once that book has been written about “Charlie” I couldn’t just do a find-and-replace and have it become “Gregory”. By then it has become hopelessly intertwined with that character’s choices, actions, desires, dreams—again, I know this might sound ridiculous, but for those of us in real life who do desire a name-change of some kind, isn’t it rooted in a similar kind of radical reinvention? We’d need to believe we truly were meant to be an “Isadora” and not a “Carol” or that we are so tired of being “Mark” and ready at last to be “Steven.”

Here’s another problem—which is that because a reader knows that the character’s name has been chosen by the author, and thus selected just like every other detail, there’s a worry about the name being too overdetermined, too obvious a symbol. I think about the story “A Country Husband” by John Cheever, which I teach every year—the protagonist of which is a man named “Francis Weed” who is kind of, well, weedy. He’s a sort of pathetic suburban father and husband who falls backwards into trying to start an affair with his kids’ babysitter and has a kind of nervous breakdown before taking up woodworking as a therapy for some sort of WW2-induced PTSD. In any event, that name, “Francis Weed” has always bothered me… it’s just too right. It feels put there on purpose by Cheever, to establish quickly in our minds that this guy isn’t the best.

Thomas Pynchon, similarly, loved to give his characters these kinds of falsely-perfect names—Roger Mexico, Oedipa Maas, Herbert Stencil, Teddy Bloat, Mike Fallopian—and in his novels these goofy monikers sometimes support an intentional sense of paranoia. (Imagine how unsettling it would be if we kept running into people whose names were perfectly suited to them: an accountant named Mr. Booker, or a bus driver named Mrs. Coach, or a coffee shop employee named Barista Styles or something.)

Pynchon probably was inspired in this by Charles Dickens (who I think got it from Shakespeare) who had a love of working little puns into the names of some of his characters— a character named “Trotter” ends up running away in The Pickwick Papers, and there is a bailiff named Fixem, and a forceful speaker named Mr. Snapper… across 15 novels Dickens created (by one count) 989 named characters, so I guess he had to get pretty creative with some of them. Today, the name “Scrooge” is a shorthand for a miserly person, thanks in part to Ebenezer Scrooge from A Christmas Carol, but the name apparently came from an pre-existing Britishism, scrouge or scruze, which meant to “screw” and “squeeze” someone. Today, thanks to Dickens’s petty orphanage official, Mr. Bumble, the word “Bumbledom” refers to the “pompous and inefficient actions of a government official.”

Imagine coming up with a character name so good that it becomes a kind of word in and of itself? Talk about pressure!

Anyway, if a name can be too perfect… and it can’t just be arbitrary, how do we proceed?

In the short story “How to be a Writer, or Have You Earned This Cliche?” by Lorrie Moore, her protagonist Francie, a college student, begins to slide absently into a career as a writer. One of the first moments where we see Francie getting proactive about her writing is when she asks her mother send her a book of baby names from home. What could be handier than a giant directory full of names? I heard a story once that in the early years of the TV show, Law & Order, various high school classmates of producer Dick Wolf began to notice that their names were popping up on his show—often attached to despicable criminals—even though many of them said they’d never known or spoken to him in school. Eventually one of them confronted Wolf about this pattern. He assured them it was nothing personal… it was just that whenever he needed a name he’d flip open his old high school yearbook and pluck something out that sounded good.

I’ve heard of authors using the Yellow Pages to similar ends, and one time, thinking of Wolf, I even grabbed an old yearbook at a yard sale for a dollar and decided, in some odd fit of egomania, that it would be fun to create a similar hubbub amongst a bunch of total strangers who’d never have any idea why their names kept coming up in my novels—only I promptly forgot all about the yearbook and misplaced it who knows where.

I know writers who jot down interesting names in their notebooks (just as I do for titles) and others who just seem to pull something out of thin air that works perfectly. Sometimes I’ve played a kind of “name game” with myself out of sheer boredom. In a coffee shop, on the train, at the mall, spot a person and try to conjure up a name for them—is he a Fred? Is she a Carolyn?

These days there are websites aplenty which can spit out names for your characters, and you can even select key variables—ethnic origin, mythological significance, Biblical connection, and so on. I’ve used them before, and the nice thing there is that you can sometimes choose something with a symbolic significance—though I suspect sometimes that these name meanings are probably about as randomly concocted as most horoscopes, at least when found in these weird online databases. One site says that “Elizabeth” means “God’s Abundance” and another might say it means “pledged to God” and another might say it is tied to the Hebrew word for the number seven. It could evoke royalty, like the Queens Elizabeth, or it could have Biblical significance of some kind—Elizabeth was the mother of John the Baptist… at least according to Wikipedia.

In whatever way, this may be helpful in imbuing the name with enough significance at least for me, the writer, to help me get going… knowing that if I sit around stressing about names all day I’m going to quickly run out of momentum on my writing. I remind myself that, by the time I’m done with the story or the book, odds are strong that I’ll have absolutely no memory even of why I chose it—I’ve had readers ask me about things like this, years later, at readings, and I’m almost always totally lost in answering. “I’m sure I had a good reason at the time,” is about the best I can ever manage.

Often a character name bears some personal significance to me, and I might stick with Elizabeth because the name reminds me of my wife’s grandmother (Hi Betsy!) or a girl that I knew in elementary school and once had to work with on a project on the ecosystem of the Jersey shoreline… perhaps there’s some tenuous connection in my mind between those real people and this character, but usually not—if there was a particularly strong connection then I’d likely avoid a direct reference like this, worried that they might think I’m calling them out somehow.

In cases where I have some real-life figure in mind, I’ll often wind up doing a little mental game of Six Degrees of Separation—in one recent story of mine, I thought about my former professor Stephen Dixon as a kind of basis for a mentor/role model figure in the protagonist’s life, and I decided to call him “A.H. Mason” because the name Dixon made me think of the Thomas Pynchon novel “Mason & Dixon” and so I jumped to Mason as a substitute. As for “A.H.”… I’m sure I had some reason, but it escapes me now. (And the protagonist, by the way, is pleasantly (for me) unnamed.)

I’ll confess that, often, when I’m sitting there writing a new piece (and I’m usually just a sentence or two in when the need for a name comes up) and wary of losing my steam, I’ll just look around my office for anything with a name on it—a sort of Keyser-Söze-esque free association—a stray business card, the singer on the album I’m listening to, and most often just the name of an author on the spine of the books nearby. In my first novel the flamboyant writer “Julian” got that name because I happened to be teaching the novel Flaubert’s Parrot by Julian Barnes that week. Later in the novel his name changes to Jeffery Oakes because I was teaching the novella “The Aspern Papers” by Henry James, which revolves around a famous poet named Jeffrey Aspern. I believe I got to “Oakes” because I, mistakenly, thought that an “Aspern” was also a kind of tree… which I’m only today discovering is wrong, and I was surely thinking of an “Aspen” all those years ago. Oh well.

My guess is that if you asked twenty writers how they usually came up with the names for their characters, they’d give you twenty different answers, any of which might be pretty weirdly particular to their process. In the end it is an strangely personal thing, a name… and so it makes sense to me that we’d all wind up with strange and personal ways of deciding on them. Will they bear some deep meaning? Will they simply come from some quickly-scanned book spine on a random shelf you found near your writing desk that day? Will you even remember in a week, a year, a decade?

All I can really conclude is that, like a good title, when you finally have something that is right—however you found it—you’ll know. It will bear some ring of truth to it, the actions that character begins to take will be the actions of a “Mike” or a “Ryan” or a “Gabrielle” or a “Esteban” and over time the name will become unchangeable, inseparable from that odd little new person you’ve made.

I love this. A character's name is so important and it takes time for it to feel right. I admit to stealing names wherever I can find them!

Kris, Great piece! I'm a big fan of getting names from headstones, especially if it's historical fiction! Not a lot of Jabidah's around these days!