A Happy Story

Garth Greenwell's "The Frog King" & hunting the most elusive form in literature

Today’s Writing Music: “Hymn #35” by Joe Pug

Today’s Reading: “How Does Garth Greenwell Make Such Wonderful Sentences?” by Christian Kiefer (a piece that inspired this one, by going micro instead of macro on this story!)

Last weekend I read an article in Education Week about “compassion fatigue” among educators during the COVID pandemic. Basically, students are more worn down than ever, and that, in turn, creates more pressure on their teachers to extend compassion. Now, I’m feeling fatigued for a hundred reasons, but none having to do with feeling compassion for the students. But then I’ve always a bit of a soft touch in this regard—lenient with paper deadlines, flexible on extra credit, minimally worried about lapses in attendance. Still, I am sensing an uptick in mental health issues among my students. And why not? Some are grieving the loss of family and friends to COVID (and other things, sometimes related, like drug abuse and suicide). Things aren’t great. They’re “back to normal” except not at all. We’re masked in classrooms that don’t feel super-well-ventilated. Mix in some climate anxiety and the fact that their educational institution is facing uncertainty and cutting back on just about everything… and it’s just a lot.

In all that, I’ve been really grateful when my students are comfortable telling me what’s going on, and not always in the context of needing extensions and leniency on absences—the other day one of my workshops evolved into the students chatting freely about mental health challenges: ADHD and negative intrusive thoughts and medications and verbalization strategies that might help… I’m blown away by how well-versed they are in the languages of self-care and mental health. (When I was in college I’d barely known how to apply terms like “ADD” or “bipolar” or “manic”.)

Eventually I began thinking about the stories I’m assigning them to read, many of which I’ve been assigning for years, and wondering if I might be compounding the problem with a bunch of sad stories. This week we read “Parker’s Back” by Flannery O’Connor, about a poor man in such existential despair that he compulsively gets tattoos all over his body. The week before, it was Loorie Moore’s “Two Boys” where a woman named Mary is having a severe nervous breakdown (but in a fun way?) Next week it’ll be Zadie Smith’s “Drinking Coffee Elsewhere” about a Black Harvard student so saddled with trauma and hardship that she eventually alienates her best friend/lover and has to drop out and move home to Baltimore.

And I love these stories. They’re beautiful. They’re some of my favorites—that’s why I teach them. They’re often quite funny. But, they are definitely sad too.

Why can’t I just assign some happy stories? How much more despair do I want to pile on?

Trouble is, a happy novel or short story is a pretty rare thing. Tolstoy opens Anna Karenina by noting “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” I can think of lots of happy moments in stories, but very few stories that are really happy all the way through—or that even just end happily.

Now, there can be benefits to reading about trauma and hardship. It may well strengthen our ability to empathize with the pain of others in real life. And it can help us to contextualize our own grief, when we identify problems we have in common with characters in a sad novel or film, we may feel less lonely, even if the characters in that story don’t actually overcome the problems in the end.

Thus sayeth Franzen, “the deepest purpose of reading and writing fiction is to sustain a sense of connectedness, to resist existential loneliness.”

And throw in DFW while we’re at it:

“Fiction is one of the few experiences where loneliness can be both confronted and relieved. Drugs, movies where stuff blows up, loud parties -- all these chase away loneliness by making me forget my name's Dave and I live in a one-by-one box of bone no other party can penetrate or know. Fiction, poetry, music, really deep serious sex, and, in various ways, religion -- these are the places (for me) where loneliness is countenanced, stared down, transfigured, treated.”

So there’s an argument there: our despair can be alleviated by spending some time in someone else’s despair. I think that’s probably true.

I just wonder if that’s the only way it can be done.

“Short stories are short and sad,” I was once taught, “because life is short and sad.”

I don’t know. Is life always short and sad? I’m cruising towards middle age now, and I’ve lived longer than some people I wish were still alive. I’m happier than lots of people, which isn’t to say life couldn’t be better. I’d always vote for living longer, being happier—but I wouldn’t say that, on the whole, the bad (and there’s been bad) outweighs the good, or that the time I’ve shared with others has been unfairly brief. It could just be that I’m lucky, or have an unusually good attitude, but I don’t know. Most of the people I know (especially ones who aren’t writers) don’t seem to go around in perpetual sadness, bereft at life’s finiteness.

And look—I’ve written sad stories, of course. Sad books, too. After my sister died of cancer at the age of 21—a life that was certainly too short, but I wouldn’t ever consider to have been sad—I wanted to write a book that looked at that kind of loss. I needed to feel less alone in that experience. But I also wanted to talk about how people recover from grief afterwards, and I made a point to continue the narrative beyond the ill character’s death, to show how everyone else deals with it.

Happiness exists. Broken places can be repaired. Losses can be mitigated. Life, full of joys big and small, can be appreciated. Celebrated.

So why are happy stories so hard to find?

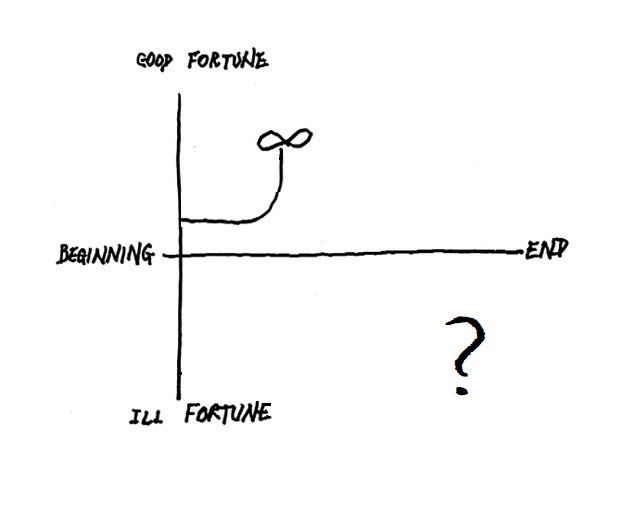

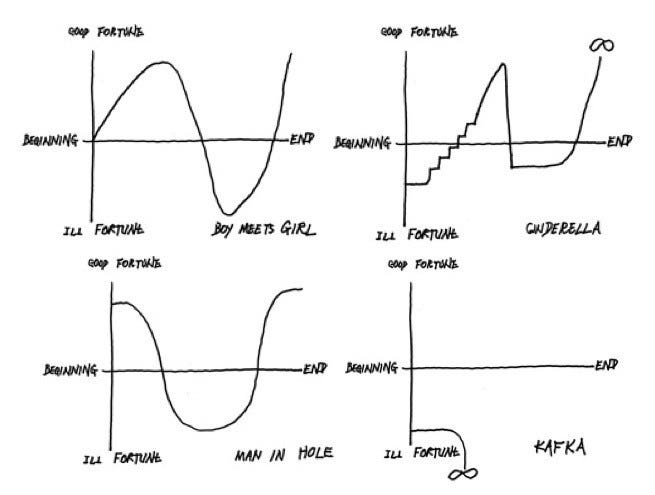

Every year in my Intro to Creative Writing Class I have the students read an essay by Kurt Vonnegut where he talks about plot and how a story can be charted on a graph, with the X-Axis going from Beginning to End, and the Y-Axis going from Good Fortune to Ill Fortune.

Vonnegut begins by recommending to write stories where the line goes up and down, and generally ends "up” in the Good Fortune zone, because, he argues, people like happy endings and that’s the secret to commercial success. In his two central examples, the “Boy Meets Girl” story and the “Man in Hole” story, the line ends higher than it began.

What many people miss about Vonnegut’s essay, which should really be read in full, is that there’s an ironic tone to all of this. In the end, he pretends to mock Hamlet for being a play where Shakespeare makes it all ambiguous. He argues that we don’t know if anything that’s happening in Hamlet is Good Fortune or Ill Fortune because we don’t know if Hamlet is actually avenging his father’s murder or if he’s just crazy.

Vonnegut closes the essay by clarifying that, actually, this is the best kind of storytelling, because it is exactly how real life is.

“The truth is, we know so little about life, we don’t really know what the good news is and what the bad news is. And if I die—God forbid—I would like to go to heaven to ask someone in charge up there, ‘Hey, what was the good news and what was the bad news?’”

My students usually like the Vonnegut essay, and especially the “Kafka” story, where things start out terrible and just get worse and worse. They think it’s very funny, which it is.

It’s also the model for a lot of modern literary fiction (if Kafka didn’t invent the “infinite sad” story model, he did make it iconic).

“Could you have a story that does the opposite?” I like to ask my students. “Where it starts off good and just gets better?”

No, they tend to agree. That would be annoying.

Gregor Samsa’s life sucks and then he turns into a giant bug/vermin, and then suffers and struggles and finally dies due to an infected wound from an apple his sister throws at him. Yes. Good good!

But if, instead, Gregor woke up—a pretty happy guy already, and then went about his day and everything just got better? If he got a promotion at work, then met a beautiful woman who fell in love with him, and then he painted a magnificent landscape painting and then came home to discover he’d also won the lottery and would never need to work again… No, no, no—we would hate that story, hate Gregor, and probably hate Kafka for writing it.

Because, we’d say, it isn’t realistic. There’s no conflict, and no struggle.

Happiness is allowed, but it must be “earned” by some equal or greater amount of hardship. The boy must lose the girl temporarily; the man must fall into the hole before he can climb back out. We find the rise and fall pleasing. Or just the fall is fine. But we can’t abide a story that is all happiness, all the time.

Or can we?

A few weeks ago, I assigned my graduate students the story, “The Frog King” by Garth Greenwell. The story stands-alone very well, but it is also the fifth of nine stories in Greenwell’s Cleanness, a sequence of linked stories that contain quite a lot of unhappiness and pain.

The narrator, unnamed, is a gay American man that teaches English to locals in Sofia, Bulgaria. But because Bulgaria is still quite socially conservative, he and other characters feel pressure to hide their sexualities.

Technically, LGBT people have rights in Bulgaria, and relationships are legal, but, as Greenwell describes, the atmosphere is not welcoming. A 2015 Amnesty International report described a “climate of fear” where anti-gay hate crimes were routinely ignored by police and prosecutors. According to a 2017 Pew Research poll, only 18% of Bulgarians favor same-sex marriage—in the US at the same time, support was at 60% and has climbed to more like 70% today. In Bulgaria, same-sex marriage has been constitutionally banned since 1991.

In Cleanness, the narrator struggles in this homophobic culture. He engages in sexual masochism that turns to violent abuse. At some point he begins a passionate love affair with closeted man named “R.” who cannot even hold his hand in public while they are in Sofia.

The point is—it’s a rough ride, and across Cleanness there’s a lot of heartbreak and violence and hardship. The book more than “earns” a bright spot, then.

“The Frog King” sits at the center of the book like an oasis. It is the rarest thing of all: a truly happy story.

Greenwell talked about the motivations behind “The Frog King” in an interview with The New Yorker’s Cressida Leyshon:

I wanted to challenge myself to write happiness. […] I wanted this central story to extend something like grace to the characters, to fully dramatize a moment in which each achieves a kind of happiness for and with the other. It isn’t that suffering or discord are eradicated in that moment, but I do think they are consolidated in, or made intelligible by, an overarching happiness. I knew that there would be a scene of intimacy in the story, but I was surprised by the form that intimacy took.

But, as we’ve discussed—this isn’t at all simple. In fact it might be one of the hardest things to do in fiction. Luckily, Greenwell is one of the very best. And because he is, I won’t attempt to paraphrase the genius of this next statement, so I hope you’ll forgive a long quote:

But writing happiness was also an aesthetic challenge. To a certain kind of temperament—my temperament, I guess—the assumption that happiness is less interesting than suffering (“happy families are all alike,” etc.) and therefore a less worthy subject for art, seems natural, self-evident. But I think that assumption is wrong. It’s an aesthetic failing but also a moral one, it seems to me now, to see happiness, even very ordinary happiness, as somehow less profound, variegated, interesting, less accommodating of insight, than other kinds of experience. I worry sometimes, in contemporary fiction, that we assume trauma is the most interesting story we have to tell. (Again, I’m speaking of my own assumptions here, not attacking a foreign view.) I wanted to write a story without trauma; I wanted to challenge myself to take happiness seriously. The surprise for me was how painful it was to write it. “And Joy, whose hand is ever at his lips, / Bidding adieu,” Keats writes, and I felt the truth of his claim that images or narratives of happiness are the best conduit for melancholy. Maybe it’s just that one never escapes one’s temperament. I hope that “Frog King” is a genuinely happy story, that the happiness the characters find with one another is genuine. It was devastating to write.

So, I wanted to share this rare, happy story with my students, but also to put together a road map for them—and for myself—to how Greenwell met this challenge. I decided to break the story down and see if the secret lay in the story’s structure.

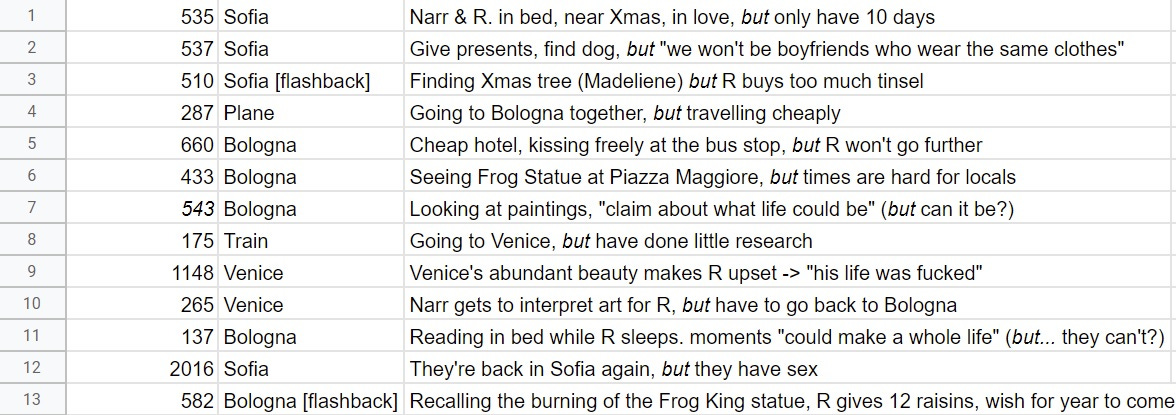

“The Frog King” is divided into thirteen sections separated by line breaks, indicating a scene change. I first traced the story’s geography. It begins in Sofia, moves to Bologna, then Venice, and then back to Bologna, and finally they return to Sofia. It’s a good shape for a story about two travelers. They go out and then come back the same way. Simple enough.

Then, borrowing a trick from George Saunders’s recent book on craft, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, I looked at what happens in each section, and where the tension comes from. (Saunders does this for a Tolstoy story, “Master and Man” about halfway through that book.)

The very first section of “The Frog King” begins with R and the narrator in bed. And, they are happy. But, about halfway into the section, we discover that this is only temporary—they have just ten days of winter vacation to be together.

This “but” is what creates the necessary tension. There’s a time bomb softly-ticking behind the rest of the action.

And the same sort of thing happens in each section. While the narrator and R remain largely happy, there is always also some but lingering around as well.

I won’t go through each one here, but I made a little chart:

This does not capture the beauty of the story overall—you’ll have to read it yourself. But you can see at least how the story follows R. and the narrator on vacation, constantly together: decorating a too-small Christmas tree, sitting closely on the cramped train, worn out by a busy day of sightseeing. It’s magical, if sometimes uncomfortable, as any vacation with a loved one can be. (Would we lose some sympathy for these two if they travelled first class? If they stayed in a four-star hotel? I think we might.)

But the temporariness of it all hangs over each section in a heartbreaking way. This happiness cannot last, so it is tinged with sadness. That’s why there is still the needed conflict and tension in the story, even though R. and the narrator never really have a fight or argument. They don’t need to. The happier they are together, and the more content the narrator feels, the worse we feel as their ten days speed to an end.

In fact—and this may be why Greenwell found it so devastating to write—the happiest moments in the story are also the saddest.

In section 11, they are back in Sofia, the vacation is over, and R. sleeps next to the narrator who is reading in bed. R. half-unconsciously rolls over and links an arm around his, and then goes back to sleep. It’s a perfect moment of intimacy. The section ends with these lines:

They could make a whole life, I thought, surprised to think it, these moments that filled me up with sweetness, that had changed the texture of existence for me. I had never thought anything like it before.

Yes. The moments could make a whole life. Just not with R., at least not in Sofia.

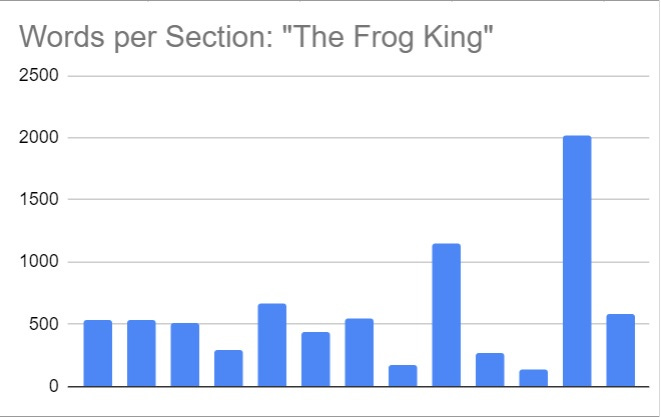

Finally, I tallied the words in each section, to try and get a sense of the balance that Greenwell strikes overall, hoping to see the structure more clearly:

The first three sections, all in Sofia before leaving, are nearly identical in length. I thought of this as the story’s base-rate, around 520 words per section.

This is then dropped by half in section 4, as they leave Sofia on the plane . Arriving in Bologna, section 5, we get a bit more than the base-rate, then a little less in 6. Then back to the base squarely again in 7.

It’s minor variations, so far. But the movement still creates power, like an orchestra getting quieter or louder, as it works through a piece of music. (Greenwell has written before about Britten’s Turn of the Screw, and his first novel is currently being adapted into an opera.)

Then, we drop even lower than before in Section 8, now on the train to Venice, and then sharply up in 9 to double the base-rate. (It’s exciting!)

And this section is wonderful. R is so overwhelmed by the beauty of the city that he flips out: saying his life is “fucked” and that he was born in the wrong place—it’s the closest to a real acknowledgment he makes to the reason that his future with the narrator is so limited.

Then Greenwell takes us back down again, for two more small sections, 10 and 11, on the return to Sofia, both of which have a quiet intimacy.

And then—the big one. The sex scene, in 12, which doubles the previous doubling in length (so now a four-times multiplier of the base-rate.) And it isn’t just exciting because R and the narrator are having sex, but, to quote DFW from earlier, its some “really deep serious sex” that just obliterates all that pressing loneliness for as long as it lasts—one reason we’re so excited that it goes on so much longer than any other part.

Section 12 comes in the place of the traditional “climax” of a story arc (double entendres are unavoidable here, so let’s just enjoy them?), where a conflict might typically erupt into a final showdown of some kind.

In other words, this is where, in another story, all of the little aggravations and annoyances that the vacationing couple has been suppressing all along come out into the open and they would wound one another in some way, perhaps even splitting up by the end.

But in “The Frog King” we get the opposite. A glorious and tender final scene between them, a peak of happiness, that almost catches us off guard because we’re so prepared for this to be the moment of dissolution.

What if it did end the other way? I think we’d still be very satisfied, in the same cynical way that we are satisfied by most stories. “Yes,” we’d say to ourselves, “Happiness is fleeting and it’s the fault of a prejudiced society and the ordinary human flaws of these two lovers.”

We’d get what we came for—a solace, a reminder that everyone else is hurting too. That nothing good can last.

How brave, then, I think, to not do this here. Greenwell frames the encounter as a hopeful one, despite all that stands in the way of these two, and the life of moments that the narrator has imagined for them. Remember the last line of the quoted section before: “I had never thought anything like it before.”

If we’ve so come to expect misery and sadness in stories, and in life, then isn’t one worthy challenge to try and create something that subverts that expectation? Where a character finds a better way? Given a glimpse of a life that contains happiness after all.

It makes me think of a pair of numbered fragments, near to the end of Maggie Nelson’s memoir, Bluets. Throughout the book, she describes a painful suffering from depression and heartbreak and all that good stuff. It’s interrupted with moments of beauty, often taking the form of objects or artworks that are blue. There’s lots of really deep, serious sex there too. But she also goes, at various points, to spend time with a friend who has been in a horrific car accident, and is now a quadriplegic. The friend spends some of her time writing letters to people, and in each she begins with a brief acknowledgment of her ongoing pains, before moving on to focus mainly on lots of other matters of more interest.

Nelson is moved by this, as was I when I first read it. How can her friend, in such an undeniably bleak situation, manage to carry on with such resiliency? How can she not let that pain become dominant?

She writes:

Imagine someone saying, “Our fundamental situation is joyful.” Now imagine believing it.

Or forget belief: imagine feeling, even for a moment, that it were true.

When I first read those lines in the book, I laughed. Snickered, even.

As if anyone could think such a thing, I thought.

Then, I sat up straight (I remember the couch I was sitting on) and caught my breath. What was I saying?

I hadn’t realized fully, until that moment, that I’d been in such a dark place. I hadn’t realized that I’d ever stopped believing, or feeling, that our fundamental situation was joyful.

And that was the beginning of a sea change for me, in how I tried to approach things.

(A book did that. Not even a long one! Really it was just three sentences in that book.)

It reminded me of another electrifying moment, where the same thing came over me, years earlier, in only two sentences.

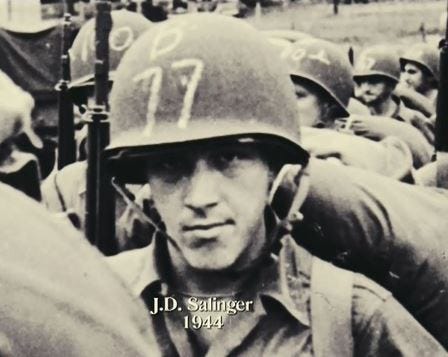

In 2011, I took a literary pilgrimage to Princeton, New Jersey, to spend a day with the papers of JD Salinger, which I wrote about for The Millions. I went down to the Firestone Library to read some of his unpublished stories about Holden Caulfield, but along the way I ran across some letters he wrote to his editor, Whit Burnett at Story Magazine.

One letter caught my eye because Salinger had sent it from Fort Monmouth, a military base near where I grew up, on the other side of New Jersey. The letter was dated 6/8/42, almost two years exactly before young Private Salinger would be in the D-Day invasion of Normandy. He was at Fort Monmouth for basic training, and reportedly spent most of the time (as he did on the front) writing short stories on his typewriter.

In the letter to Burnett, Salinger talks about his love life, saying he “met a little number in the local metropolis who’s going to let me write at her house nights.” And then moved on to a crisis he was feeling about his work.

Tragic, gritty stories about the war were in vogue at the time, and he knew that writing them was the fastest way to his dreams of publication. But, he told Burnett, he was having trouble doing it.

“I’m beginning to feel that no writer has the right to tear his characters apart if he doesn’t know how, or feel that he knows how (poor sucker) to put them together again. I’m tired… my God, so tired… of leaving them all broken on the page with just ‘The End’ written underneath.”

I was tired of the same thing then, and I still am. I’ve tacked these words up near my writing desk, along with Maggie Nelson’s, as a reminder to always remember to avoid the cynical approach, the tragic grit, the dissolution of love. To do the harder work it takes to write a story that puts its characters back together again.

I don’t have compassion fatigue, but I might have sad short story fatigue. If you feel the same, then I’m grateful to have stories like “The Frog King" that generously give us other options, and even more grateful to share them here.

Writing Towards the Fun #15: The challenge here is suitably simple… but not. It is just this—write about a happy experience. A happy memory. It can be tinged with something else (regret, nostalgia, loss) if you want, but try to make the happiness the central focus. It doesn’t even need to be a whole story, just a scene.

Got nothing? Spend the week looking for something and when you find it, write it as soon as you can.

Have Fun!

What makes something a 'happy story'? Are happy moments enough or can they be invalidated by a sad ending?

I'm not seeing many that agree with my interpretation--including the author (yikes!)--but I have some challenges with the straightforward 'happy story' label.

Yes, their vacation together is blissful, but it is largely so because it represents the fulfillment of repressed wants and needs they have not been able to experience in their regular life.

This fulfillment would be uncomplicatedly happy if we thought it was going to continue, but the story ends with us thinking that the status quo has not changed. So there definitely was beauty and happiness, but much of it came from the character's understanding that this was an abnormal, temporary thing.

Furthermore, not only has the status quo not changed, but I think the return to normalcy is the beginning of the end. If such a blissful vacation is not enough to change the status quo, what is? How can life go back to normal after knowing such beauty is possible?

The characters are going to be troubled by these questions, maybe they work through them, but I think not based on some of the characterization of R. who is a fatalist.

That's why I think R.'s tears are partly because he is touched by the tenderness of the protagonist's love, but also because he is mourning that he cannot provide the type of relationship the protagonist is ultimately after